An Introduction to Politics for the Politically Clueless

If you have always felt somewhat lost on the political landscape, this primer is for you.

By Patrick Carroll – October 28, 2022

With midterm elections around the corner (here and gone), many are undoubtedly trying to brush up on their knowledge of politics, having mostly ignored the topic since the last election. Maybe you know some of these people. Maybe you are one of these people.

For those trying to get a crash course in politics before they vote, the process can be a little daunting. You might try reaching out to a politically-knowledgeable friend, but chances are you’ll end up getting more of a rant than answers to your simple questions.

So, in an attempt to provide less of a rant and more of an introduction, here are some basic ideas that will help you get oriented on the political landscape. Note, this isn’t about specific platforms or candidates, nor is it a civics lesson—there are plenty of other places to get that information. Instead, this is more of an introduction to political philosophy. It’s about the principles and big ideas that motivate the various positions.

The Fundamental Question of Politics

The starting point of politics is a very simple question: What should the government do? How you answer this question basically determines where you fall in the political realm.

Whether you’re a Republican or Democrat or somewhere in between (or somewhere else, or completely lost), there are certain things almost everyone thinks the government should do. For example, most people think the government should provide things like police, courts, roads, and national defense.

There are other government initiatives, however, that are more contentious. This would include issues like gun regulation, drug prohibition, public schooling, and business regulations like the minimum wage.

Another way of thinking about the fundamental question of politics is to ask “what decisions should the government make for us, and what decisions should individuals be allowed to make for themselves?” As Thomas Sowell said, “The most basic question is not what is best, but who shall decide what is best.”

Should the government have the final say as to whether people use cocaine, or should that decision be in the hands of the individual? Should the government raise taxes, meaning they decide what to do with a certain sum of money, or should they lower them, meaning the individual decides what to do with that money?

When framed this way, it becomes clear that the more the government does—that is, the more the government makes decisions on our behalf—the less we are free to make our own decisions. Every decision the government makes for us is a decision we can’t make for ourselves. In the words of Ronald Reagan, “As government expands, liberty contracts.”

This insight can be used to develop a very basic political spectrum. At one extreme you have the government making virtually all decisions for its citizens, to the point where the government has “total” control over its people. That would be totalitarianism. At the other extreme you have the government making absolutely no decisions, at which point you have no government, that is, anarchism.

Each political philosophy fits somewhere on that spectrum, and where it fits depends on how much it says the government should control our decisions.

The Political Compass

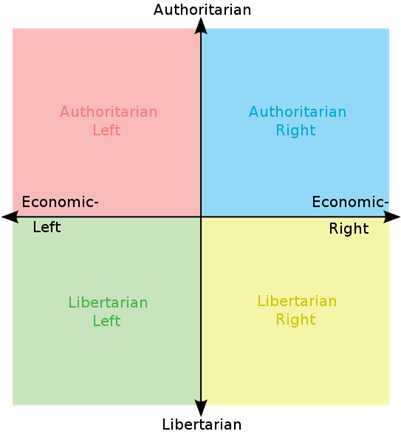

The spectrum above has the advantage of being simple, but it doesn’t always do a good job of representing where people stand. For example, if someone wants lots of government involvement in the economy (regulating businesses, minimum wage laws, high taxation, lots of government programs etc.) but also desires strong social freedoms (free speech, drug legalization, etc.) it can be hard to represent that position on a 1-dimensional axis. Thus, to make these distinctions somewhat clearer, political philosophers have come up with a 2-dimensional political compass that splits economic and social views into their own categories. Economic views are represented by the horizontal axis and social views are represented by the vertical axis.

Though there are two axes instead of one now, the premise is very much the same. At one extreme you have total freedom and no government interference (the far right economically and far down socially). At the other extreme you have lots of government and virtually no freedom (the far left economically and far up socially).

It’s worth noting that “socially liberal” views are sometimes called “libertarian” in contrast to “authoritarian” as in the graphic above. But this is different from the philosophy of libertarianism, which favors both economic and “personal” liberty.

It’s also important to clarify “socially liberal” in this context. The term is often taken to mean libertinism. In the political context, however, “socially liberal” does not mean condoning any particular set of lifestyle choices. It just means rejecting the criminalization of lifestyle choices that do not violate anyone else’s rights.

With some artistic license, the previous 1-dimensional spectrum could be overlaid on the political compass. It would essentially be a line running diagonally from the top left corner (totalitarianism) to the bottom right corner (anarchism).

Republicans (aka conservatives) and Democrats (aka liberals) are both near the middle of this compass. The main difference between them is that Democrats generally lean toward more social freedom and less economic freedom (bottom left quadrant) whereas Republicans lean toward less social freedom and more economic freedom (top right quadrant). So Democrats might push for higher taxes and looser drugs laws, whereas Republicans will push for lower taxes and more stringent drug laws.

Libertarians (bottom right quadrant) are often seen as a weird mix of some Republican and some Democrat positions (“socially liberal, fiscally conservative”), but the above framing hopefully makes it clear why this isn’t the case. Libertarians are simply for freedom in all its forms, and it is the liberals and conservatives who have the strange mixes, championing freedom in some areas while trying to restrict it in others.

A Question of Values

Where you fall on the political spectrum ultimately comes down to what you value. If you want the government to provide lots of services but stay out of people’s personal lives, you’ll probably fit best with progressives/liberals. If, on the other hand, you believe there should be stricter social rules but that the government should largely leave the market alone, chances are you’re more of a conservative. And if you just want the government to leave people alone in every domain, you’re probably a libertarian.

These are only generalizations, of course. Every side has its nuances, and as you talk to people from different perspectives you’ll probably start to pick up on them. In fact, the best way to learn is to talk with people who disagree with you. Even if they are the ranting type, asking questions of political nerds can really help you understand where they’re coming from. You might still disagree, of course, but you will at least have a better grasp of the political landscape.

And who knows? They might actually change your mind.

Patrick Carroll has a degree in Chemical Engineering from the University of Waterloo and is an Editorial Fellow at the Foundation for Economic Education.