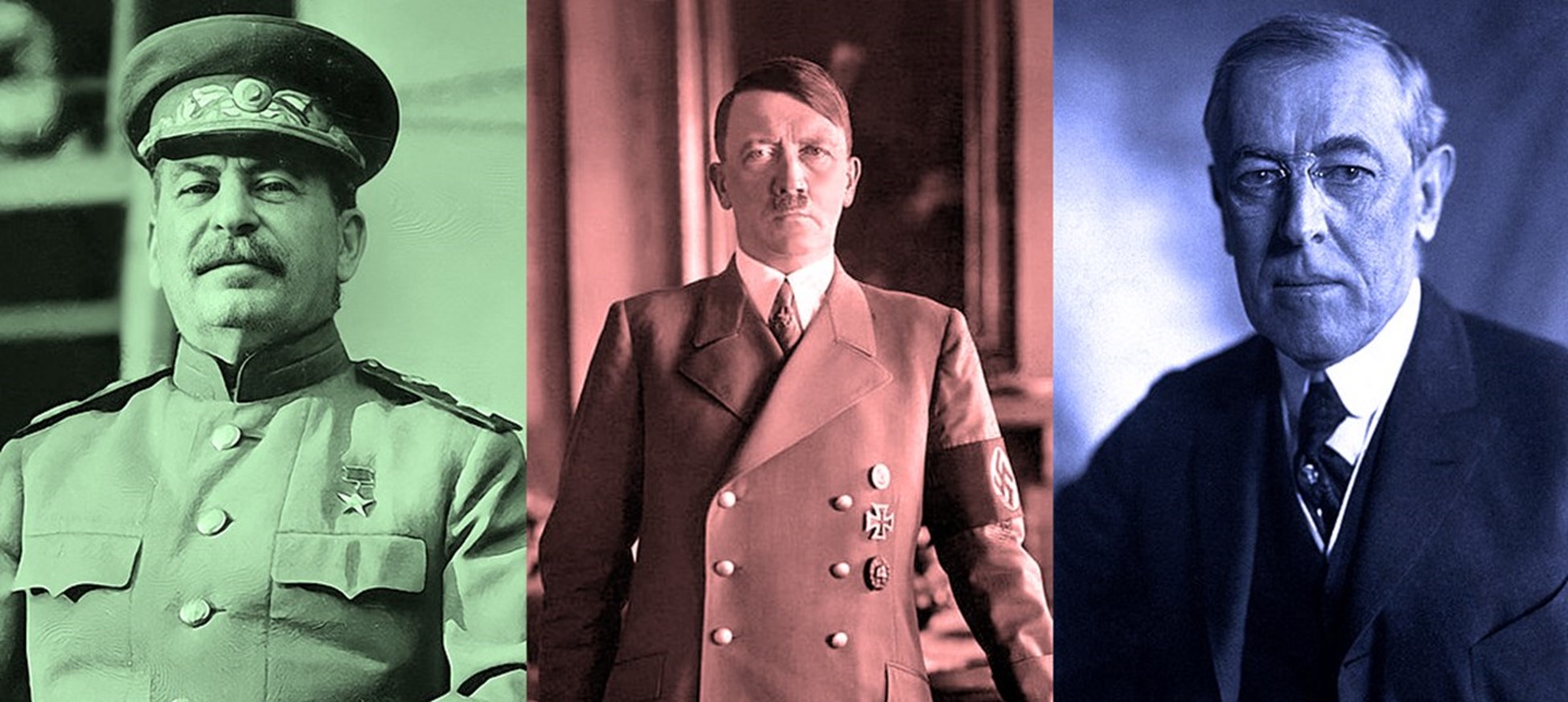

Composite image by FEE | Public domain: Stalin, Hitler, Wilson

The Deadly Sins of Politics

Politics isn’t exempt from the allure of the deadly sins. Some political systems even magnify the allure…

By Axel Weber & Dan Sanchez – November 1, 2022

The nineteenth-century philosopher Joseph de Maistre once wrote “Every nation gets the government it deserves.” This is true in a sense because, as Ludwig von Mises later wrote, “public opinion is ultimately responsible for the structure of government.” The beliefs and values of a people determine the institutions they embrace or accept.

The influence goes the other way, too. Different systems of government create different incentives. Some institutions foster virtue, while others foment vice.

Let’s consider some historically important political ideologies and the moral qualities they reflect and promote.

- Socialism

Socialism is, as Winston Churchill put it, “the gospel of envy.” A people afflicted with envy and resentment will gravitate toward socialism.

Psychologist Jordan B. Peterson discussed the connection between envy and Marxist socialism in particular:

“There is the dark side of it, which means everyone who has more than you got it by stealing it from you. And that really appeals to the Cain-like element of the human spirit. ‘Everyone who has more than me got it in a manner that was corrupt and that justifies not only my envy but my actions to level the field so to speak, and to look virtuous while doing it.’ There is a tremendous philosophy of resentment that I think is driven now by a very pathological anti-human ethos.”

Socialists are wrong to think that “leveling the field” will lift up the have-nots. But even if they are disabused of that economic error, envy may drive them to cling to socialism anyway, out of a malicious desire to harm the “haves.”

As Mises wrote of socialists:

“Resentment is at work when one so hates somebody for his more favorable circumstances that one is prepared to bear heavy losses if only the hated one might also come to harm. Many of those who attack capitalism know very well that their situation under any other economic system will be less favorable. Nevertheless, with full knowledge of this fact, they advocate a reform, e.g., socialism, because they hope that the rich, whom they envy, will also suffer under it.”

Just as envy advances socialism, socialism stimulates envy by inviting the masses to participate in “legal plunder” (as the French economist Frédéric Bastiat put it) of the rich and affluent.

- Fascism

In the twentieth century many countries fearfully turned to fascism to protect themselves from communism. Many in those countries believed that if communists and their ideas were violently suppressed, their revolution would be nipped in the bud. Fear turned to wrath, as anti-communist fascists violently cracked down on any dissent that might destabilize the state.

“The great danger threatening domestic policy from the side of Fascism,” as Mises wrote, “lies in its complete faith in the decisive power of violence.”

The wrath and violence of fascism is ultimately self-defeating.

“Repression by brute force,” Mises wrote, “is always a confession of the inability to make use of the better weapons of the intellect — better because they alone give promise of final success. This is the fundamental error from which Fascism suffers and which will ultimately cause its downfall.”

Wrath drives fascism, but fascism also stirs up wrath by fomenting tribalism and inviting members of society to use political violence to settle their differences.

- Progressivism

Progressivism is alluring to those who imagine they can “optimize” people through social engineering. But, as Leonard E. Read illustrated in his classic essay “I, Pencil,” society is so vastly complex, that this is a pipe dream. To think one can centrally plan society, one must fancy themselves to have quasi-divine omniscience. In simple terms, progressivism is an ideology of excessive pride. As Sen. Ron Johnson put it:

“The arrogance of liberal progressives is that they’re just a lot smarter and better angels than the Stalins and the Chavezes and the Castros of the world, and if we give them all the control, and they control your life, they’re going to do a great job of it. Well, it just isn’t true.”

Progressives are incorrect in their assumption that they know how to run other people’s lives better than those people themselves. Even if they were hypothetically smarter and more ethical than any single member of the rest of society, they would still be wrong.

The amount of information any expert can handle at a given moment is infinitesimal in comparison to the sum of information all individuals have. Letting individuals be free to cooperate through the price system decentralizes the use of knowledge and actually results in more information being used than a centrally planned system of experts. As Friedrich Hayek explained:

“The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design. To the naive mind that can conceive of order only as the product of deliberate arrangement, it may seem absurd that in complex conditions order, and adaptation to the unknown, can be achieved more effectively by decentralizing decisions and that a division of authority will actually extend the possibility of overall order. Yet that decentralization actually leads to more information being taken into account.”

Thus, the progressive’s faith in technocratic power stems from supreme epistemic arrogance.

“It is insolent,” Mises wrote, “to arrogate to oneself the right to overrule the plans of other people and to force them to submit to the plan of the planner.”

Progressivism not only stems from pride, but stimulates it, because overweening power tends to go to people’s heads.

An Alternative?

Must we pick from among political systems that are afflicted by one vice or another? Thankfully not. There is a virtuous alternative: namely, classical liberalism. Whereas socialism, fascism, and progressivism are dominated by the “deadly sins” of envy, wrath, and pride, classical liberalism embodies the “capital virtues” of charity, temperance, and humility.

Where socialism is based on envy, classical liberalism fosters charity. Classical liberals believe in voluntary exchange of goods and services which provides avenues for philanthropy. One can only be charitable when there is a choice to donate or help others. Forced charity is not truly charitable, for there never was a choice, just as giving away something you don’t actually possess is not a sign of selflessness.

As Murray Rothbard wrote, “It is easy to be conspicuously compassionate when others are forced to pay the cost.”

Where fascism is wrathful, classical liberalism has temperance. Fascists see dissent and difference as dangerous. Classical liberals see peaceful debate and competition as the key to progress. Classical liberalism embodies temperance in the way it upholds the rights of everyone, even those who are illiberal. Under fascism, violent hostility toward differences is the rule; under classical liberalism, peaceful voluntary cooperation for mutual benefit is the rule.

Where progressivism is prideful, classical liberalism has humility. Classical liberalism is humble because it doesn’t presuppose what society should value; it assumes that all individuals have goals that they alone know best how to achieve. Classical liberalism knows the limits of what any individual can know and consequently finds no reason to bestow power to any expert over the rest of society. As Hayek wrote, “All political theories assume […] that most individuals are very ignorant. Those who plead for liberty differ […] in that they include among the ignorant themselves as well as the wisest.”

As it says in the Bible, “the wages of sin are death.” And indeed, the sin-ridden ideologies of socialism, fascism, and progressivism have yielded a staggering death toll. In contrast, the blessings of liberty include, not only peace and prosperity, but the encouragement and freedom to lead a virtuous life.

Axel Weber is a fellow with FEE’s Henry Hazlitt Project for Educational Journalism and member of the PolicyEd team at the Hoover Institution. He holds a Bachelor of Science in Economics from the University of Connecticut.

Dan Sanchez is the Director of Content at the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE) and the editor-in chief of FEE.org.