Americans feel less free, don’t trust leaders post-COVID pandemic: poll

By Casey Mattox – March 12, 2022

Some three-fifths of Americans in a YouGov/AFP poll reviewed by The Post voiced a negative view of the US government’s public messaging during the pandemic, and the lack of trust could have dire consequences for future crises.

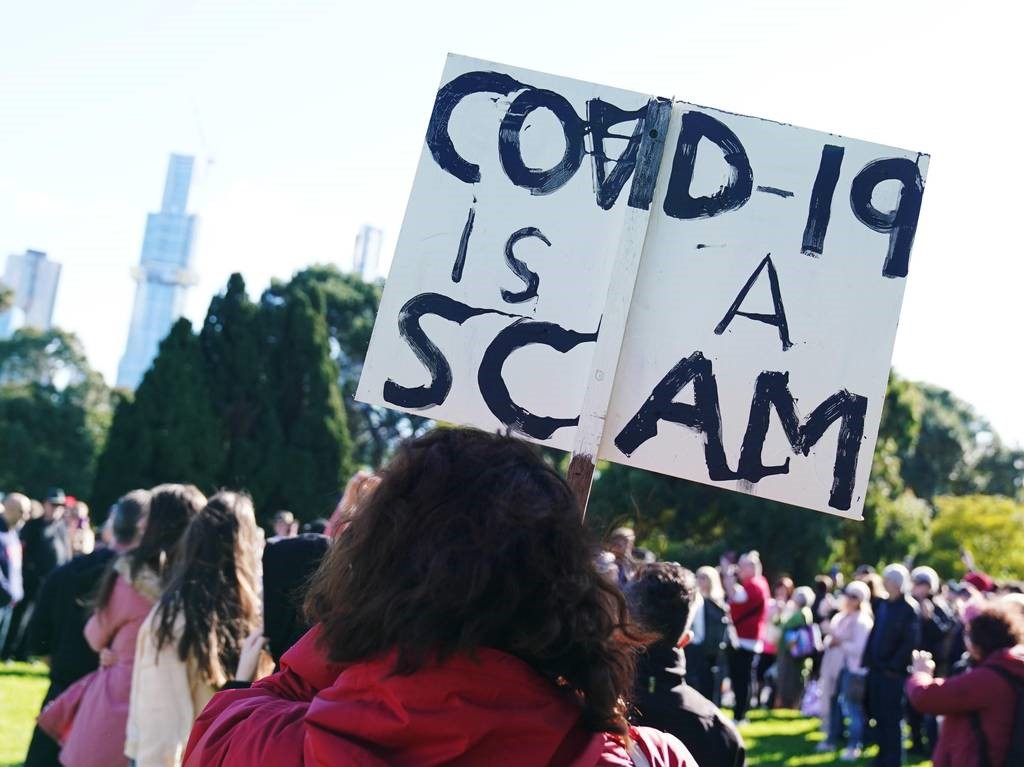

For many Americans, March 11, 2020 is the day the coronavirus started to feel like a real pandemic, as our elected officials rushed to respond to the crisis. Two years later, Americans’ view of their civil liberties — and their confidence in public officials — has taken a beating.

A new poll conducted by YouGov and Americans for Prosperity (AFP) and released exclusively to The Post reveals that Americans feel their core freedoms are less secure than before the pandemic. This is true often by substantial margins: 42% feel less secure about voicing their opinions, 43% feel less secure about their freedom to protest, 36% feel less secure about their freedom to exercise religious beliefs.

This is bad news for our foundational rights. Even if our rights remain on solid legal ground, the perception they are not can cause us to think twice about speaking up.

It’s also bad news for our public officials.

While a healthy skepticism of government power is wise in a democracy, in a true crisis public officials must make snap decisions to protect the public. Whether people follow those decisions depends, in part, on their confidence in the leaders making them. Unfortunately, when asked about every single institution or office in the YouGov/AFP poll, the majority of respondents said their trust in those institutions had dropped.

Nearly three in five Americans said the government did a “somewhat” or “very poor” job clearly communicating to the public about data or reasoning regarding any pandemic restriction or requirement. And 54% thought government officials did a “somewhat” or “very poor” job applying any restrictions or requirements to all people (including themselves) equally.

After two years of mask mandates, 42% of Americans feel less secure about voicing their opinions, while 43% feel less secure about their freedom to protest.

Almost two years ago, I wrote about how public officials might “promote public health, regain trust, and ensure liberty.” These poll results show they’ve failed in every respect. What lessons should leaders take from this?

First, don’t treat citizens as subjects. Top-down answers don’t work. Instead, take more advantage of the knowledge of local civic and community leaders — people on the ground who are closest to their communities and their needs. When they come up with creative ways to hold drive-in church services and organize outdoor rallies in the open air to keep their communities both safe and engaged, accept their help instead of arresting their congregants and activists.

On July 15, 2021, Jen Psaki called on social media companies to vet COVID “misinformation” on their platforms. But such censorship has led many to question the government’s own message.

Second, keep your restrictions as focused and limited as possible. If you’re facing a virus most easily spread in confined, indoor spaces, should we arrest a lone surfer in the ocean or fill skate parks with sand? No — that’s sweeping rather than precise. As new information becomes available, reassess, revise and refine.

Third, comply with your own rules. During the pandemic we saw constant examples of public officials decreeing one thing and doing another, such as California Gov. Gavin Newsom who went maskless at a dinner in 2020 despite his own mandate. Hypocrisy is nothing new in politics. But when you claim emergency powers and a responsibility to keep people safe, you must demonstrate that you are complying with your own public health rules. Convince people you aren’t asking them to give up any temporary liberty you aren’t willing to give up yourself.

Finally, respond to bad information with better ideas, not bans. Governments are rarely fans of dissent. But dissent is what drives discovery and accountability. Especially during a pandemic, where the science evolved along with the virus, censorship of “misinformation” has led many to question the government’s own message.

The Economist found that democracies — in part because of the free flow of information — experience lower mortality rates during epidemics than their non-democratic counterparts: “During an outbreak, for example, constructive feedback about how government policies are working can help guide a more dynamic response. Non-democratic societies often restrict the flow of information and persecute perceived critics.”

The last year has shown that top-down answers don’t work. Instead, local civic and community leaders should be relied upon for more targeted, practical solutions.

While 30% of respondents, including a bare majority of Democrats, believe the government should ban the posting of misinformation online, most Americans in the YouGov/AFP poll say they shouldn’t. And the youngest cohort in the survey, those 18 to 24, were least likely to call for an outright government ban of misinformation.

At some point in the future, there will be another crisis where public officials have to make time-sensitive trade-offs, and Americans will need to trust them to do their jobs correctly and appropriately. Sadly, after the experience of the last two years, those officials will begin with a citizenry predisposed not to trust that their civil liberties are safe in their hands.

Casey Mattox is senior vice president of legal and judicial strategy at Americans for Prosperity.