How FDR Used Tax Dollars To Buy An Election

Most Americans knew FDR hadn’t brought the U.S. out of the Depression, but they weren’t about to vote against their own perceived interests.

By Tyler Curtis – October 11, 2022

5 MIN READ

In modern democracies, we tend to over-interpret the outcome of an election. When one candidate prevails over another, by however large or small a margin, we conclude that “the people” must be endorsing that candidate’s entire policy program. In reality, the process by which people choose whom to vote for is complex, messy, and often irrational.

Few historians understand this better than David Pietrusza. The author of several books on presidential elections, Pietrusza has the uncanny ability to take the reader back in time and experience what it was really like for voters and candidates to live through an intense presidential campaign.

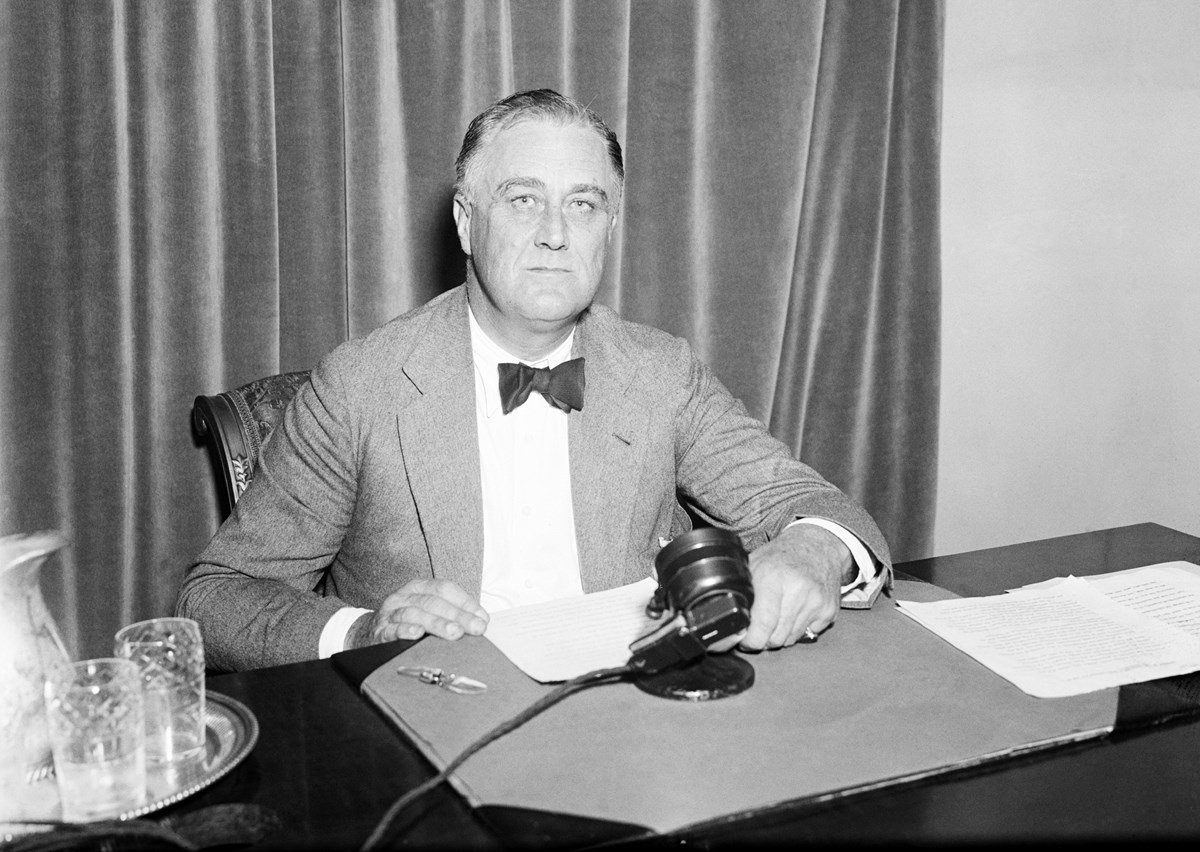

In his latest book, “Roosevelt Sweeps Nation: FDR’s 1936 Landslide and the Triumph of the Liberal Ideal,” Pietrusza tackles what appears to have been an unexciting election year. As the subtitle indicates, Franklin Roosevelt won his second term in 1936 by an overwhelming margin, taking nearly 61 percent of the popular vote and winning 46 of 48 states.

The final vote tallies make it seem like the 1936 campaign had no drama. Roosevelt cruised to victory on the back of his great policy successes, as the country gave him an indisputable mandate to continue with the New Deal, right?

Wrong, says Pietrusza. Roosevelt’s reelection actually masked the truth about how controversial the New Deal really was. It was so controversial, in fact, that many in Roosevelt’s camp were worried it would cost him the election. According to one poll conducted just 10 months before the balloting began, only 38 percent of respondents said they supported the New Deal.

Americans had good reasons to be opposed to the New Deal. As Pietrusza points out, Roosevelt’s economic policies weren’t working. Although things weren’t as bad as they were when FDR took office in 1933, the Great Depression was far from over. At the end of 1935, the unemployment rate stood at a staggering 20.1 percent, and real GDP was still lower than it was in 1929 when the Depression began.

For any other politician, these kinds of economic figures would have spelled certain doom. But in the hands of a born politician like FDR, the dismal economy was actually an asset. In his public speeches, Roosevelt expertly pinned the blame on what he called “economic royalists”: greedy businessmen whose unscrupulous activities were preventing a full economic recovery.

This was nonsense, of course. Though some new banking regulations helped to calm the financial waters early on, the rest of the New Deal was an anti-growth grab-bag of senseless price controls, deficit spending, and onerous taxation.

Unfortunately, there were precious few people who were willing to push back on Roosevelt with any meaningful force. The Republican presidential nominee, Kansas Gov. Alf Landon, was a squish. A progressive at heart, Landon actually supported most of FDR’s New Deal programs. “I have cooperated with the New Deal to the best of my ability,” he declared. Landon not only agreed with Roosevelt’s policies, but he also supported granting the president “unusual powers” to help alleviate the “national emergency.”

Landon’s campaign line was that the Roosevelt administration was inefficient and that he would raise the government’s standard of competency. For voters looking for an alternative to FDR’s quasi-dictatorial New Deal, Landon was uninspiring, to say the least. His personality left a lot to be desired too. A generally dull speaker, few people were really excited to come out to hear him, even if they might consider voting for him.

Still, his bland personality and muddled political philosophy notwithstanding, Landon enjoyed a slight edge over Roosevelt, with Gallop reporting a 272-259 electoral college lead just a few months before the election was held.

But even if Landon had been a firmer critic of the New Deal, he still wouldn’t have won. For despite the general unpopularity of FDR’s economic policies, millions of people now relied upon the federal government for their livelihood. As Pietrusza writes, “New Deal programs put people on the payroll — people who would look upon FDR as their savior and their friend, who would vote not just for him but for the entire Democratic ticket. And so would their families.”

Though most Americans recognized that Roosevelt hadn’t brought the country out of the Depression, recipients of government assistance were not about to vote against their own perceived interests. As Democratic Sen. Carter Glass bragged, “[T]he elections would have been much closer had my party not had a four billion, eight hundred million dollar relief bill as campaign fodder.” In other words, FDR bought the election with taxpayer dollars.

Glass’ admission is just one of many eyebrow-raising quotes generously peppered throughout Pietrusza’s chronicle. “Roosevelt Sweeps Nation” is a gritty tale. Pietrusza takes us behind the scenes and reveals the true character and intentions of FDR, as well as his political allies and enemies. The result is a thrilling and informative exploration of an overlooked but important presidential election.

Tyler Curtis is a loan officer at a community bank in Missouri. He received a bachelor’s degree in economics from Missouri S&T. He has also written for the Foundation for Economic Education, the Mises Wire, and Intellectual Takeout.