By Daniel Greenfield – December 31, 2022

(Posting this article has become an annual tradition ever since the grim end of 2012. It’s a reminder that the end of each year ushers in unknowns, but also opportunities for heroism. History does not stand still, and we should never assume that we know how it will come out. Daniel Greenfield)

The next year sweeps around the earth like the hand of a clock, from Australia to Europe and across the great stretch of the Atlantic it rides the darkness to America. And then around and around again, each passing day marking another sweep of the hours.

While the year makes its first pass around the world, even if it doesn’t feel like there is much to celebrate, let us leave it behind, open a door in time and step back to another year, a century past.

December 31, 1912.

The crowds are large, the men wear hats, and the word ‘gay’ means happy. Liquor is harder to come by because the end of the year has fallen on a Sunday.

There are more dances and fewer corporate brands. Horns are blown, and the occasional revolver fired into the air, a sight unimaginable in the controlled celebrations of today’s urban metropolis.

The Hotel Workers Union strike fizzled out on Broadway though a volley of bricks was hurled at the Hotel Astor during the celebrations. New York’s Finest spent the evening outside the Rockefeller mansion waiting to subpoena the tycoon in the money trust investigation. And the Postmaster General inaugurated the new parcel service by shipping a silver loving cup from Washington to New York.

On Ellis Island, Castro, a bitter enemy of the United States, and the former president of Venezuela, had been arrested for trying to sneak into the country while the customs officers had their guard down. Gazing at the Statue of Liberty, Castro denied that he was a revolutionary and bitterly urged the American masses to rise up and tear down the statue in the name of freedom.

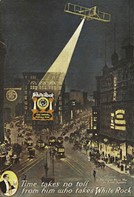

Times Square has far fewer billboards and no videos, but it does have the giant Horn and Hardart Automat which opened just that year, where food comes from banks of vending machines giving celebrating crowds a view of the amazing world of tomorrow for the world of 1912 is after all like our own.

We can open a door into the past, but we cannot escape the present.

The Presidential election of 1912 ended in disaster. Both Taft and Roosevelt lost and Woodrow Wilson won. In the White House, President Taft met with cabinet members and diplomats for a final reception.

Woodrow Wilson, who would lead America into a bloody and senseless war, subvert its Constitution, and begin the process of making global government and statism into the national religion of his party, was optimistic about the new year. “Thirteen is my lucky number,” he said. “It is curious how the number 13 has figured in my life and never with bad fortune.”

In Indianapolis, the train carrying union leaders guilty of the dynamite plot was making its secret way to Federal prison even while the lawyers of the dynamiters vowed to appeal.

The passing year, a century past, had its distinct echoes in our own time. There had been, what the men of the time, thought of as wars, yet they could not even conceive of the wars shortly to come. There were the usual dry news items about the collapse of the government in Spain, a war and an economic crisis in distant parts of the world that did not concern them. The Federal Reserve Act would be signed at the end of 1913, partly in response to the economic crisis.

Socialism was on the march with the Socialist Party having doubled its votes in the national election. All three major candidates, Wilson, Roosevelt and Taft, had warned that the country was drifting toward Socialism and that they were the only ones who could stop it.

“Unless Socialism is checked,” Professor Albert Bushnell Hart warned, “within sixteen years there will be a Socialist President of the United States.”

Hart was off by four years. Hoover won in 1928. FDR won in 1932.

At New York City’s May Day rally, the American flag was torn down and replaced with the red flag, to cries of, “Take down that dirty rag” and “We don’t recognize that flag.”

The site of the rally was Union Square, one of the locations where Black Lives Matter hangs out, taking over from Occupy Wall Street and generations of radicals.

There was tension on the Mexican border and alarm over Socialist successes in German elections. An obscure fellow with the silly name of Lenin had carved out a group with the even sillier name of the Bolsheviks. China became a Republic. New Mexico became a state, the African National Congress was founded and the Titanic sank.

There was bloody fighting in Benghazi where 20,000 Italian troops faced off against 20,000 Arabs and 8,000 Turks. The Italians had modern warships and armored vehicles, while the Muslim forces were supplied by voluntary donations and fighters crossing from Egypt and across North Africa to join in attacking the infidels.

The Italian-Turkish war has since been forgotten, except by the Italians, the Libyans and the Turks, but it featured the first strategic use of airships, ushering in a century of European aerial warfare.

There was a good deal going on while the horns were blown and men in heavy coats and wet hats made their way through the festivities.

World War I was two years away, but the Balkan War had already fired the first shots. The rest was just a matter of bringing the non-phosphorus matches closer to the kindling. The Anti-Saloon League was gathering strength for a nationwide effort that would hijack the political system and divide it into dry and wet, and, among other things, ram through the personal income tax.

Change was coming, and as in 1912, the country was no longer hopeful, it was wary.

Change was coming, and as in 1912, the country was no longer hopeful, it was wary.

The century, for all its expected glamor, had been a difficult one. The future, political and economic, was unknown. Few knew exactly what was to come, but equally few were especially optimistic even when the champagne was flowing.

If we were to stop a reveler staggering out of a hotel, stand in his path and tell him that war was five years away and a great depression would come in on its tail, that liquor would be banned, crime would proliferate and a Socialist president would rule the United States for three terms, while wielding near absolute power, he might have decided to make his way to the recently constructed Manhattan Bridge for a swan dive into the river.

And yet we know that though all this is true, there is a deeper truth. For all those setbacks, the United States survived, and many of us look nostalgically toward a time that was every bit as uncertain and nerve-wracking as our own.

December 31, 1912 was a door that opened onto many things.

Our December 31 is likewise a door, and if a man in shiny clothes from the year 2120 were to stop us on the street and spill out everything he knew about the next century, it is likely that there would be as much greatness as tragedy in that tale.

As the year sweeps across the earth, let us remember that history is more than the worst of its events, that all times bear the burden of their uncertainties, but also carry within them the seeds of greatness. Looking back on this time, it may be that it is not the defeats that we will recall, but how they readied us for the fight ahead.

America has not fallen, no more than it did when the clock struck midnight on December 31, 1912. Though it may not seem likely now, there are many great things ahead, and though the challenges at times seem insurmountable and the defeats many, another year and another century await us.

Daniel Greenfield is a journalist investigating Islamic terrorism and the Left. He is a Shillman Journalism Fellow at the David Horowitz Freedom Center

[HFL Editor: 1913 may be known as the year of the pivot with the introduction of official Progressivism in DC, the 16th (income tax) & 17th (states give up their sovereignty) Amendments, the Federal Reserve (3rd party economic interference) that changed our Constitutional America. Pray 2023 improves.]