Computer generated 3D illustration with a Golden Calf

As Christianity Declines, We Must Confront The Threat Of Pagan America

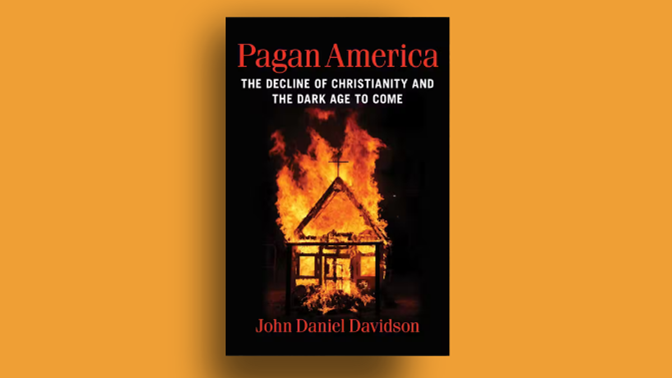

Federalist Senior Editor John Daniel Davidson’s new book, Pagan America: The Decline of Christianity and the Dark Age to Come, offers a sobering assessment of the threats to the American way of life as religiosity declines.

By Casey Chalk – April 2, 2024

8 MIN READ

In 2010, sociologist James Davison Hunter, famous for, among other things, popularizing the term “culture war” provocatively argued in To Change the World: The Irony, Tragedy, and Possibility of Christianity in the Late Modern World that conservative Christian attempts to restore Christian values on American society were misguided, if not harmful.

Such efforts to “redeem America,” argued Hunter, not only hadn’t worked but would never work, both because they represented an erroneous grasp of how cultures change, and because they distracted the faithful from their real task as Christians. Instead, Christians should pursue what Hunter termed “faithful presence,” by focusing on living authentically Christian lives in our families, communities, and spheres of influence, rather than programmatic political or cultural solutions.

Almost 15 years removed from Hunter’s book, things look quite a bit gloomier for Christianity in America. Over that period, the number of religiously unaffiliated adults has almost doubled to 28 percent; weekly church attendance rates have dropped from about 40 percent to 30 percent; and 80 percent of American adults believe religion’s influence on public life is declining. De-Christianizing trends are particularly salient among younger generations, who are less likely than older Americans to believe the government should protect religious liberty. Almost half of Gen Z-ers think the First Amendment should not protect hate speech (which, according to many Americans, includes religious criticism of LGBT identities and behaviors).

We inhabit an America less friendly to Christianity than was the case halfway through Obama’s first term as president. Various political, cultural, and demographic trends suggest that antipathy will only grow in the years to come. In Pagan America: The Decline of Christianity and the Dark Age to Come, Federalist Senior Editor John Daniel Davidson offers an even more pessimistic perspective: We’re already in a post-Christian society that is paganizing (or re-paganizing, to take the long historical view) in ways that will make life increasingly difficult and dangerous for American Christians.

From Pagan Exploitation to Christian Human Dignity

The historical narrative grade-school and collegiate students learn today portrays pre-modern societies across the world living in peaceful symbiosis with nature… until they were brutally defeated, if not destroyed by an intolerant Christian civilization. Davidson relates a number of historical anecdotes proving how blinkered this story is. Whether we are talking about the ancient societies of the Mediterranean, pagan northern Europe, or indigenous America, all demonstrated a profound disregard for (or exploitation of) the weak and vulnerable. Davidson cites the Vikings, Aztecs, and 19th-century kingdom of Benin as civilizations engaging in ritual human sacrifice to appease angry, bloodthirsty gods, but there are plenty of others.

Judaism and then Christianity repudiated such societies, built as they were on power, fear, and the fulfillment of base sensual desires. It was the church that rejected the common Roman practice of abandoning (if not murdering) unwanted children, stopped human sacrifice in northern Europe, and discouraged polygamy in the Americas and Africa.

Citing Tom Holland’s popular book Dominion, Davidson writes: “Human rights, equality, care for the poor, mercy for the condemned, refuge for the persecuted, charity for the marginalized and downtrodden: these were never self-evident truths.” Rather, “they are unmistakably Christian ideas that rely on specifically Christian doctrines, without which they are unintelligible.” Obviously, Christian societies were by no means perfect and were often hypocritical, but it’s undeniable that they ushered in a paradigmatic shift via their understanding of the dignity of the human person.

This was no less true of the culture of the founders, who, though coming from a variety of religious traditions, recognized the need for the maintenance and propagation of religion and morality for the survival of the republic, something that can be found across their letters, including in the Federalist Papers. Indeed, the establishment of religion continued at the state and local level for many years after the signing of the Constitution, indicating that the framers did not intend pure religious indifferentism or a strict separation of church and state.

In his telling, Davidson departs from the postliberal thesis popular with some conservatives (and particularly Catholics) that the problems with classical liberalism we see today were “baked into the cake,” so to speak, of our constitutional republic, but are rather an aberration. (Given postliberalism’s popularity, I wish Davidson would have engaged more with its arguments.)

When the Pro-Religion Wheels Fell Off

Despite the founders’ intentions, Davidson identifies trends that, observable in the 19th century and accelerating in post-World War II America, undermined the nation’s Christian identity. Several Supreme Court decisions are emblematic of this shift. Cantwell v. Connecticut (1940) in its forbidding of the “determination by state authority as to what is a religious cause” effectively mandated a strict state religious neutrality, imposed national secularism, and rendered government incapable of defining what is and is not a religion. Everson v. Board of Education (1947) decreed, “Neither a state nor the Federal Government can, openly or secretly, participate in the affairs of any religious organizations or groups, and vice versa.” Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971) gave us the “lemon test”: If a government action 1) lacks a “secular purpose,” 2) has the “primary effect of promoting or disparaging religion,” or 3) excessively “entangles” the government in religious matters, then it violates the Establishment Clause.

Yet, as Davidson ably argues, secular laws and institutions are never purely religiously neutral — they will always make moral claims originating from some conception of right and wrong and will coerce citizens into what the state deems the “correct” behavior. As our culture’s self-understanding of Christianity declines, the secular regime’s tensions and conflicts with various Christian institutions increase.

This explains, for example, the state’s coercive tactics against churches during the height of the pandemic, forcing them to remain closed for months under penalty of law because they provided “nonessential” services. Of course, as we all observed, there were plenty of hypocritical double standards when it came to enforcement of Covid policies, given the kid gloves authorities employed toward race-related protests.

Such contradictions lead to Davidson’s most interesting and provocative thesis: that an increasingly secular America is not ushering in a rational, neutral, and indifferent regime, but rather a revitalized form of paganism. Indeed, that irrationalism is on full display in the growing popularity of superstitious beliefs such as horoscopes, crystals, tarot, occultism, wiccanism, and an unwavering faith in “the science” even when what “the science” declares is reversed only a short time after it was considered dogma. But Davidson is just getting started here.

He argues that neo-paganism is visible across our polis. Abortion and euthanasia, for example, are new forms of human sacrifice; transhumanism and transgenderism reflect man’s attempt to usurp God’s authority over nature. Moreover, warns Davidson, if minors have the autonomy to decide their own “gender,” what’s stopping our paganizing establishment from also claiming that minors have the autonomy to pursue sexual relations with whomever they choose? Artificial intelligence, in turn, serves as a “godlike” artifice, a “Promethean power” to be worshiped.

What’s a Christian to Do?

For now, the persecution of Christians in America has largely been restricted to ostracism and censorship. Davidson projects that to change, “through mandatory reeducation, the loss of parental rights, fines and financial penalties, and even imprisonment.” Indeed, there are already signs of this, including government persecution of Christian businesses, leveraging laws to shutter Christian foster care services, FBI targeting of pro-life activists, and federal collaboration with social media companies to restrict freedom of speech. In light of these trends, Christians must gird themselves for a “long persecution and a long fight.”

Echoing Rod Dreher and his famous “Benedict Option,” Davidson writes:

The primary task of American Christians in the generations to come will therefore be the preservation and propagation of the faith at all costs. And the costs will be high. Yes, that will require being prepared to be poorer and more marginalized, but it will also require being prepared to be arrested, imprisoned, and martyred.

Yet Davidson argues for something different than Dreher, what he calls a “Boniface Option,” after the medieval missionary to Germanic peoples who so aggressively combatted paganism and its rituals that he was ultimately martyred. This is a more combative, political approach than Dreher’s. Though Davidson acknowledges that Washington and other major cities are likely a lost cause, he exhorts readers to take back local institutions such as city councils, public libraries, and school boards. Christians, he urges, should be banning drag performances and pornographic and pro-trans books from local libraries and schools, and applying economic pressure by “refusing to patronize businesses and brands that embrace pagan morality.”

It’s true: Christians cannot simply escape into their little ghettoes. The Christian religion cannot avoid witnessing in the public square, and its adherents, whether they be doctors, lawyers, teachers, government employees, business owners, or landscapers, cannot help but have their work informed by their faith.

That battle, even if it is a losing one, must be fought in every place inhabited by faithful Christians, an exemplar of Hunter’s “faithful presence” in this disastrously post-Christian society. I have no doubt the result will be the making of many saints. Whether it is also the making of a revitalized Christian society in America remains to be seen.

Casey Chalk is a senior contributor at The Federalist and an editor and columnist at The New Oxford Review. He has a bachelor’s in history and master’s in teaching from the University of Virginia and a master’s in theology from Christendom College. He is the author of The Persecuted: True Stories of Courageous Christians Living Their Faith in Muslim Lands.

Leave A Comment