BY: Alison Bucklin – August 25, 2020 (emphasis added)

Slavery did not begin with European settlers in 1619. It did not even begin on the North American continent in 1619. The Africans who disembarked from the White Lion in 1619 were simply patient zero for a mutation of an age-old virus.

At that time the only continent in the world where chattel slavery (buying and selling individuals as a commodity) was not practiced was Europe. It was common from China to Polynesia, India to Japan, and on both continents of the Western Hemisphere. Slavery has been practiced since before the beginning of recorded history.

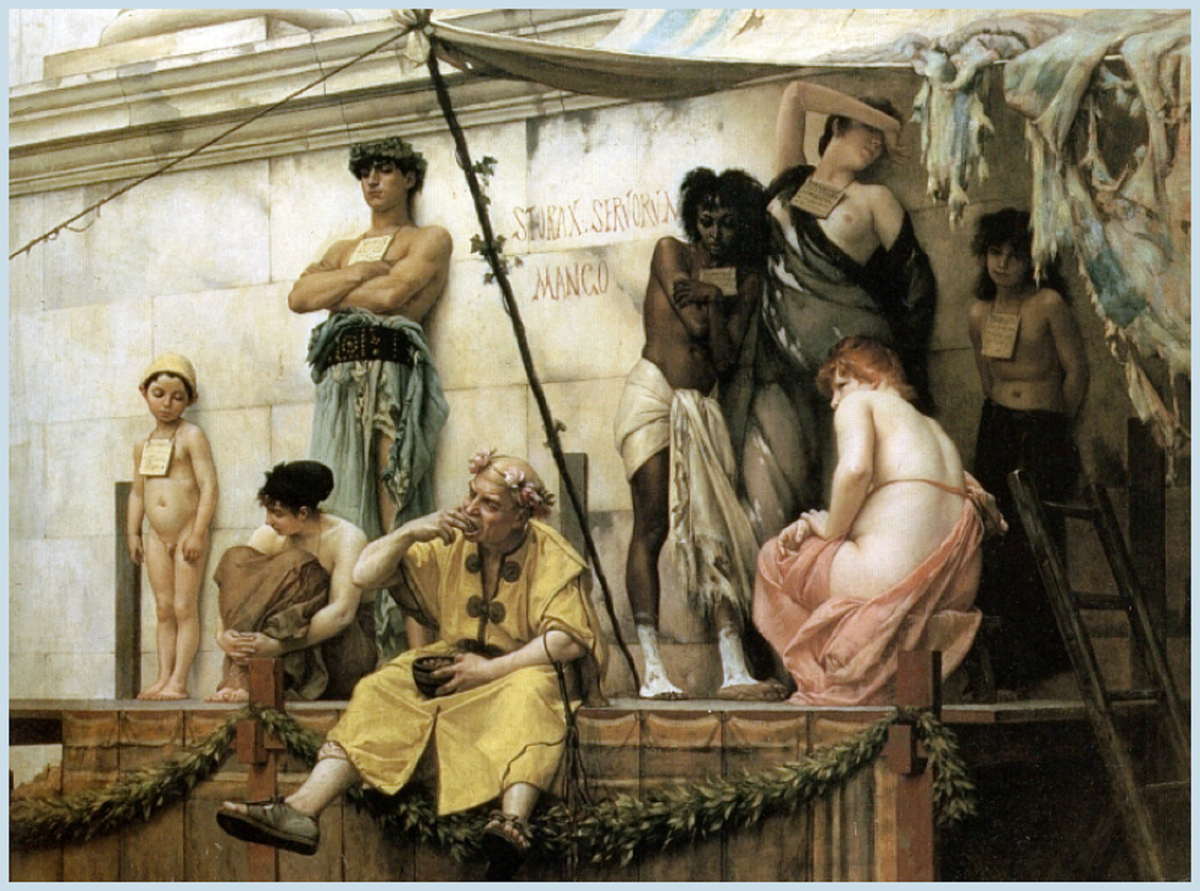

Archeological evidence indicates that chattel slavery existed in the Middle East as early as 3200 BC. The practice continued unabated through Sumerian, Egyptian, Persian, Carthaginian, Greek, and Roman civilizations. Although some slaves could rise to positions of power, most lived under conditions of brutality and degradation which rivaled the cotton fields of the American South, the sugar cane plantations of the West Indies, and the silver mines of Peru.

Following the fall of the Roman Empire, the Christian church began pressuring their rulers to abolish slavery, first prohibiting slavery of co-religionists and eventually extending the prohibition to all persons. By the 7th century, chattel slavery had disappeared in the Byzantine Empire, and in most of the rest of Europe by the 10th century.

Scandinavians lagged behind, prohibiting the practice over the next few centuries as their kings converted to Christianity. Iberia (Spain and Portugal) came late to the table, as they had been preoccupied with fighting for their freedom from 700 years of Moorish occupation.

Other forms of unfree labor continued, notably serfdom and indenture, but these were ameliorated by legal protections, the possibility of freedom, and a certain degree of autonomy.

In Africa and North America, inhabited largely by nomadic peoples and subsistence farmers, slavery was usually limited to war captives, criminals, and debt indenture; however, chattel slavery arose as societies grew more complex and powerful and needed a steady source of labor. The Aztec Empire, for instance, required a continuous infusion of war captives. Most were slaughtered for religious ceremonies, but a considerable number were sold for labor. The Inca Empire did not, technically, practice slavery; however, kings were both sons and priests of the Sun god and effectively owned all of the people and property in their domains.

Before, during and after the Arab conquest of the Middle East and Northern Africa, the Arab slave trade in and around the Mediterranean took up where the Roman Empire had left off. During the 8th and 9th centuries most slaves were taken from Europe, Persia, the Caucasus and adjoining regions.

During the 18th and 19th century alone around 1.5 million European Christians were captured and sold. From the 7th century to the fall of the Ottoman Empire in 1920, scholars estimate that anywhere between 12 and 25 million slaves were taken from Africa across the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea, and the Sahara. Zanzibar and Timbuktu were, respectively, hubs of this trade for East and Central Africa.

Slavery continues to be practiced in parts of Islamic Africa until the present. In the 1950s, Saudi Arabia‘s slave population was estimated at 450,000. Up to 200,000 South Sudanese were enslaved during their 1983-2005 civil war. Slavery was not criminalized in Mauritius until 2007.

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to follow in the Arabs’ footsteps, taking their first African slaves in 1435. Over the next 4 centuries, Spanish and Portuguese, Dutch and English, French and Norwegian captains alike participated in the brutal trade. From the 16th to the 19th centuries around 12 million slaves were taken to the Americas. This figure does not take into account the large number who died on their way to the coast. By the mid-18th century, slaves were Africa’s main export, representing as much as 95 percent of its value.

African tribes competed among themselves to supply the growing demand for labor in the New World and raiding for slaves became a way of life for the armed elite. African rulers became rich by controlling the supply of captives to the Atlantic slave trade, the Kingdom of Dahomey and the Ashanti tribe being prime examples, but, in the long run, the entire continent was impoverished. Buyer and seller alike were corrupt, complicit, and culpable.

Slavery, then, is endemic to the human race. The only force in history known to have had an effect on this ugly feature of human nature is Christianity. This begs the question, “Why was Christianity not proof against the arrival of the infection in the New World?” The answer is that the virus mutated.

The element of race was added. Those whose consciences would have troubled them about enslaving white Christians pointed to cultural and physical differences between Africans and Europeans, and looked for creative ways to enlist the Bible against the gospel of reconciliation. Cultural Christians turned a blind eye to the phenomenon, as the profits were so great. Even free blacks and Native Americans were not immune. It took committed, practicing Christians to start the long task of eradicating this new form of an old disease.

Christian abolitionism in North America began its struggle in the late 17th century with the Society of Friends, or Quakers. The movement soon spread to Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Methodists, and Baptists (called Nonconformists or Dissenters because they disagreed with the Church of England), and it is likely that their marginalized status made them more sympathetic to other outsiders.

Anglicans were also important contributors to the movement. Key figures internationally were John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, and William Wilberforce, who led the fight to end slavery in Great Britain. In the United States, key figures included William Lloyd Garrison, Harriet Beecher Stowe, John Brown, and former slaves Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and Sojourner Truth.

Although far from all Christians were abolitionists. All abolitionists appear to have been Christian. Unfortunately, following the passage of the 13th and 14th Amendments, the church seems to have felt that its work was done.

Convalescence and recovery were left to the former slaves themselves. It is no coincidence that the leaders of their communities were pastors. But the environment, still openly infected with the residue of the mutated virus, was still unhealthy. A few key steps were taken during the middle of the 20th century, led by luminaries from Rosa Parks to Dr. Martin Luther King. But the gospel was soon overtaken by the government as the treatment of choice, and the hard work of rehabilitation was replaced by the easy out of comfort care. Pain was alleviated at the cost of the abandonment of faith and addiction to government programs, while the providers reaped power and profits.

Where once financial rewards went to the participants in the slave economy, those who profit from dependence and division are now politicians, bureaucrats, agitators and academics. They have no incentive to eradicate the disease.

The only antidote is still Christianity, the gospel of reconciliation, administered in large doses, for life – both in order to live, and for as long as you live. But it works. “For [Christ] himself is our peace, who has made the two groups one and has destroyed the … dividing wall of hostility.…” [Eph 2:14] However, peace is not the end of the struggle. Even after the dividing wall is broken down, freedom still needs to be sought and defended.

Because new mutations have arisen, as they always have and always will. At present Marxism, with its twin offspring Communism and Socialism, has infected a significant portion of the population. These are the most comprehensive forms of slavery the world has yet devised, as they enslave entire populations rather than discrete segments. And it is a particularly insidious mutation, as it is disguised with language that mimics the concern for the poor that is a key characteristic of Christianity. But slavery is, in essence, coerced labor for another’s profit, and so is socialism.

Unfortunately, exposure does not confer immunity, and religious fervor is not enough to eradicate it. We must understand the threat, and resolve to face it. We must not let ourselves “be burdened again by a yoke of slavery, for it is for freedom that Christ has set us free.” [Gal 5:1]

Alison Bucklin is a compassionate wife, mother, daughter, sister, niece, aunt, friend and a lover of all of God’s creatures.