by Rodney Dodsworth, August 19, 2019

June 9th, 1787.

Our Framers were not about to substitute one national tyrant with another. All had lived under the abuses of George III and his royal governors. Less well-known today is the 1776 reaction by the newly independent States. In an 18th century version of “power to the people,” the States set up overly democratic governments featuring weak governors. Although the rules varied from State to State, most legislatures appointed governors, made judicial appointments, and even served a judicial roles in some cases. Property wasn’t secure as the legislatures ran from one extreme to another according to the passions of the day. They violated wholesale Charles De Montesquieu’s admonition against combining legislative and executive power.

So, Americans had suffered under strong executives and suffered under weak ones; they wanted neither. They sought a balance in which power was properly divided among branches, each with their own rights and prerogatives, such that no man or group of men could rule by fiat.

As opposed to the headless Articles of Confederation, the ideal administrator in our new republic was powerful enough to check legislative mistreatment, yet was sufficiently limited in his own powers. Furthermore, per Montesquieu, this man must not be the tool of any institution, faction, or collection of factions which we know today as political parties. The American President was independent of the other branches, but not isolated from them.

We cannot overstate the Framer’s efforts to avoid the executive abuses of George III as well as the democratic abuses of overly popular government. The chief executive must depend on the foundation of all republics, the people, yet not be so beholden to them that he and the office descend into tyranny.

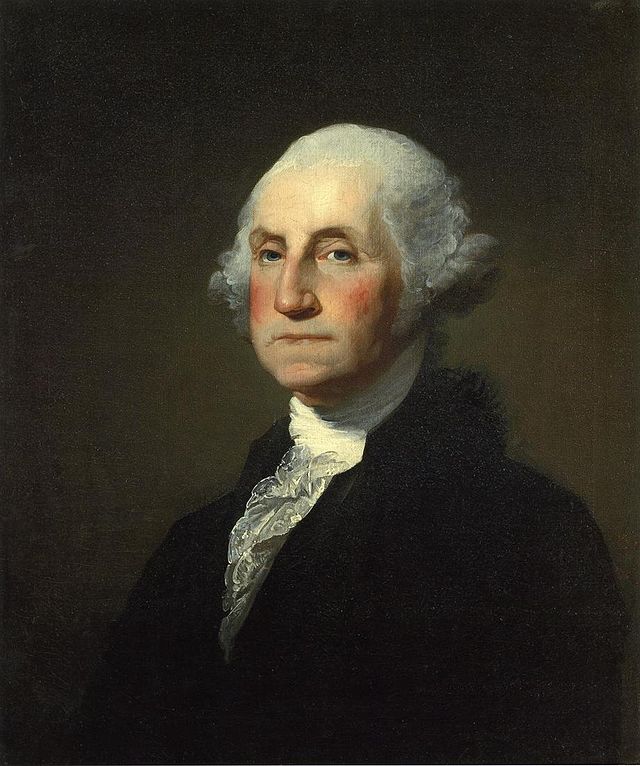

On June 9th, the Committee of the Whole returned to executive elections. Since the goal was to provide an endless succession of men equal to George Washington, delegates sought an electoral method that identified and appointed such men. Why not rely on the judgement of other chief officers to identify in others the requisite traits in public virtue and leadership?

Elbridge Gerry (MA) proposed executive election by the State governors in proportion to each State’s representation in the Senate. At this point in the proceedings Senate membership was proportioned, like the House, according to population. There’s also been a shift in thinking of the chief executive away from his mere duty to execute the law. Unlike the English monarch, he wasn’t to be the heart and soul of the nation, but perhaps he should be its face, the man other nations regarded and respected as the limited leader of a free people.

So, instead of a tight connection with the authors of the law per the Virginia Plan, Gerry moved to establish an executor independent of Congress. He described election by governors as analogous to the principle observed in electing the other branches of the national government: the first branch being chosen by the people of the States, and the second by State legislatures. He did not discern any objection to this method and supposed the governors would select fit men for the office. Afterward, it would be their interest to support the man of their own choice.

While Gerry’s chief executive was not a tool of Congress, Virginia Governor Edmund Randolph opposed State governors as electors because the chief executive would lack the confidence of the people. Furthermore, expect State governors to select a man from amongst themselves, meaning covert side deals and corruption. He doubted the election ever of men from small States, and wasn’t confident in the governor’s familiarity with men outside their States. Finally, governors are very close to their legislatures, and would likely direct their governor’s vote for a national chief executive.

A national Executive thus chosen would not likely defend with vigilance & firmness the national rights against State encroachments. He did not envision that governors would feel the interest in supporting the national Executive which had been imagined. As Randolph put it, “They will not cherish the great oak which is to reduce them to paltry shrubs.”

Gerry’s motion for governors as executive electors was defeated, 10-0-1.

Delegates had so far considered and rejected elections by the people, the House of Representatives, Congress, State Legislatures, Governors, and through temporary electors from special districts. All except one method shared a fatal deficiency: sitting Presidents beholden to men with interests too narrow for the man who was to represent the American republic.