[Editor: This is the entire 14 part series by Rodney Dodsworth and his Article V Blog on the Founders invention and evolution of the presidency and the Electoral College. A day-by-day account behind the closed doors of the 1787 Constitutional convention.]

By Rodney Dodsworth, Aug 5, 2019

Part I

Not until the waning days of the Philadelphia Convention did our Framers complete their plan of the Electoral College. In contrast, Article I elections to Congress and Article III appointments to the Scotus were taken care of weeks before. What took so long to determine Article II electors?

The answer is that the Constitution isn’t linear. In a linear design, adding or amending one clause, one Section, one Article doesn’t affect previous clauses, Sections and Articles. In contrast, our Constitution is non-linear. It more resembles a puzzle in which the authority of one branch necessarily affects the power and reach of the other two branches. So it was in 1787 with the design of the Executive.

Delegates found enough difficulty thrashing out the particulars of a Legislature and a Judiciary, whose purposes and general structures were familiar to generations of Americans. What about a chief Executive? How many? Rome did quite well for much its history with two consuls. Annual or multi-year terms? How many terms? Maybe a life term like English monarchs? Should the Executive be subservient to the Legislature? Was he strictly an administrator, an executor of the law like most state governors? Should he lead armies? Popular election? Election by the state governors? English monarchs had Privy Councils, so why not the American CEO? Some time passed before delegates went beyond the term, “Executive.” After all, anything stronger might be interpreted as subversive intent for a nascent monarch. And thanks to George III, there were plenty of well-known executive abuses to prevent.

Alongside all of this was cracking the tough nut of Separation of Powers. While we take the idea and its boundaries for granted today, our Framers at the start of the convention weren’t so sure. Where the British monarch had theoretical veto power over Parliamentary bills, it hadn’t been used since 1688. British kings, without input from Parliament, appointed judges. Why violate separation of powers and make judicial appointments contingent on Senatorial consent? How can republican states and an umbrella government with a chief executive coexist?

This and more is why familiarity with the Presidency as it evolved over the summer of 1787 is worthwhile. In their finished product the Framers carefully matched electors to each of the four major institutions (House, Senate, Presidency, Judiciary) with the duties of the institutions. Those who propose to change these electors should first consider the logic of the Framers’ original design. Explain the Framers’ error. Second, they must describe the benefits of their proposals and how they promote good governance and liberty.

Just as the Framers’ experience under the Articles of Confederation showed that committees weren’t suited to Executive power, and our experience since 1913 proves that popularly elected senators cannot fulfill their Constitutional duties, so too is the National Popular Vote an unwise, ill-considered and destructive proposal. If carried out, I fear it will doom the remains of our republic.

In subsequent squibs we’ll examine the pertinent convention debates surrounding this new guy to history, the President of the United States, and why the Framers’ Electoral College is so essential.

***

| Shaping the Electoral College, Part II

by Rodney Dodsworth, August 8, 2019 |

June 1st, 1787.

Not until the waning days of the Philadelphia Convention in September did our Framers complete their plan of the Electoral College. As with the other major institutions of their Constitution, (House, Senate, Judiciary) they were careful to properly match electors to these institutions, meaning those who installed the members of the House, Senate, Presidency and Judiciary had a natural interest in the duties of the institutions. It is why, for instance, the people did not elect Senators and states did not elect Representatives to the House.

Delegates established a quorum eleven days after the scheduled start date of May 14th. I’ve wondered at times if this is evidence of the hand of God. The delay gave the VA delegation’s James Madison time to convince his fellow Virginians to present a revised plan of government, a starting point for the convention other than the Articles of Confederation. Ratification of piecemeal amendments to the Articles failed in 1781 and 1783.1 Why revisit old territory? By offering a plan that addressed the nation’s problems the VA delegation seized the high ground and directed the early debate.2

On June 1st, VA Governor Randolph introduced Resolution 7: “Resolved that a National Executive be instituted; to be chosen by the National Legislature for the term of —– years, to receive punctually at stated times, a fixed compensation for the services rendered, in which no increase or diminution shall be made so as to affect the Magistracy, existing at the time of increase or diminution, and to be ineligible a second time; and that besides a general authority to execute the National laws, it ought to enjoy the Executive rights vested in Congress by the Confederation.”

A Magistracy? America booted its last Majesty only eleven years earlier, and the Virginians propose another? Charles Pinckney (SC) stood at once to urge a “vigorous Executive,” and James Wilson (PA) moved to support a single man for the office. With this, a hush fell over Independence Hall. A single menacing man? It conjured visions from the past – unrestrained royal governors, a crown, a scepter! Ben Franklin, whose unassuming wisdom saved the convention a couple times, asked his fellows to deliver their sentiments. The non-recordation of individual votes and the parliamentary rule of secrecy, both during and after the convention allowed delegates to freely offer their opinions and change them as the Constitution took shape over the summer. No one need fear political repercussions for their day-to-day votes and speeches.

Randolph saw the “fetus of monarchy” in a unitary Executive. Liberty was safer in three sets of hands. When properly designed, the office could be just as vigorous and responsible. Great Britain should not be “our prototype.” But why shouldn’t the best British principles, if consistent with American manners and genius, be adapted? Even the youngest delegate was born an Englishman and had probably boasted that he lived in the best and freest kingdom on earth. George III betrayed British principles and forced America to find liberty in republican government.

What Powers? Roger Sherman (CN) declared the duty of the Executive magistracy nothing more than carrying out the will of the legislature, which expressed the supreme will of society. Like a modern corporate CEO, Sherman’s Executive carried out the will of the republic’s board of directors and nothing more.

To alleviate fears of a single Executive, James Madison (VA) went further than Sherman and proposed to better define the Executive’s duties. Where extensive powers would be safer in the hands of more than one Executive, proscribed powers could be left in a single man. He motioned to amend the clause, so the Executive would execute the laws, appoint officers and execute other powers not legislative or judicial. Mr. Wilson seconded.

Our Framers were well versed in men’s dispositions and shortcomings. They knew that power intoxicates and corrupts. Governments tend naturally toward despotism. I see every day in this convention a concern for properly matching adequate power and no more to the branches and offices of the new government. In similar fashion, as we shall see, the methods devised to elect or appoint members of the three branches were devised to minimize corruption and shady backroom deals so common in the British system.

Charles Pinckney (SC) regarded Madison’s amendments as redundant, and therefore unnecessary. When the great work is completed, we will find that the Executive and Judicial departments were granted general executive and judicial powers under the Constitution. Congress, on the other hand, would be strictly entitled to legislative powers, herein granted.

Executive Electors. James Wilson (PA), the product of Pennsylvania’s semi-radical political system, endorsed direct election of the Executive by the people.

Roger Sherman (CN), who had seen enough ruinous democracy since the revolution, found safety in an Executive elected by the Legislature. To him, an Executive independent of the Legislature led to tyranny.

The delegates considered various lengths of Executive service. Some went with the possibility of reelection, some with single long terms. In their deliberations there was always a tug between two concerns – how to avoid truncating the service of competent men needed by their country, yet prevent the rise of a political class dedicated to the trappings of power and little else.

In closing the day, an ever-democratic James Wilson preferred the people elect both houses of the legislature as well as the Executive. But he couched popular election of the executive with a caveat that made its way into the Electoral College when he said, ”the objects of choice in such cases must be persons whose merits have a general notoriety.” Indeed. From Wilson we can see at this early juncture the Framers sought only the best men for the executive office and will soon realize the key to finding such men was to carefully design a set of electors suited to the task. As opposed to today’s widespread mythology, the Framers’ first purpose was not to prevent urban voters from dominating the presidential election process.

- McLaughlin, A. C. (1905). The Confederation and the Constitution. New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers. 172.

2. As for the VA delegation, Patrick Henry declined his appointment due to family issues. Richard Henry Lee also declined. Both were fierce Anti-Federalists. Had either attended, we cannot know the outcome. Perhaps no new Constitution of government at all.

***

Shaping the Electoral College, Part III

by Rodney Dodsworth, August 12, 1019

June 2nd, 1787.

Delegates once again met in committee, the committee of the whole, a parliamentary device that allows a more open exchange of views without the urgency of a final vote. For instance, in a committee setting George Washington, the President of the Convention, sat with his fellow VA delegates. After debating, the committee submits its conclusions to the Convention where the same people deliberate once again, as if they hadn’t before, and where the votes are generally final.

Executive Electors. Recall James Wilson’s (PA) closing comments from yesterday in which he wished to see popular election of men with general notoriety, a respected nationwide reputation like that of George Washington. Today, Wilson proposed the people elect Electors from special districts who in turn appoint the Executive. An advantage of this mode is that it would produce more confidence among the people in the first magistrate than an election by the national Legislature per the Virginia Plan. We can thank James Wilson for what would eventually evolve into the Electoral College.

Elbridge Gerry (MA) feared corruption if the National Legislature appointed the executive. Imagine the sleaze and bribery! He leaned toward election by the state legislatures either directly or by selecting nominees for electors to elect. The people ought not to act directly even in the choice of electors, being too little informed of personal characters in large districts, and liable to deceptions. His idea would find its way into Article II, “Each state shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors . . . “

But, at this early juncture, Wilson’s motion to set up districts in which the people elect electors failed 7-2. The committee-of-the-whole then agreed by an 8-2 vote with the appointment of the Executive by the first branch of the Legislature for a term of seven years.

Presidential Character. George Washington was the model; he was the ideal, the sort of man our Framers sought. Wilson mentioned national notoriety. But what of the motivations of other men?

Benjamin Franklin (PA) saw “inconveniences in the appointment of salaries; I see none in refusing them, but on the contrary, great advantages.” Franklin feared the sort of men attracted to well-paying federal offices. Everyone in the room was familiar with the widespread, open, and infamous British corruption of saleable offices. He went on in words that ring true down through the ages, “Sir, there are two passions which have a powerful influence on the affairs of men. These are ambition and avarice; the love of power, and the love of money. Place before the eyes of such men, a post of honor that shall be at the same time a place of profit, and they will move heaven and earth to obtain it.”1

In closing, he pointed out the public virtue of George Washington who didn’t accept a salary for his eight arduous years of military service. Franklin did not believe that salaries are necessary to attract patriots to government.2

Removal From Office. John Dickinson (DE) proposed the Executive be removable by the National Legislature on request by a majority of the states. I’ve wondered if this arrangement wouldn’t be preferable to, as practiced today, the ineffective impeachment by the House and conviction by the Senate. Considering the absence of the States from the Senate since 1913, I admittedly favor the additional federal element of state impeachment, even though today’s Senate is thoroughly corrupted by democracy.

In response to Dickinson, Gunning Bedford (DE) seconded the motion. Roger Sherman (CN) would have the National Legislature alone responsible for Executive removal. George Mason (VA) warned of Executive dependency if he was both elected by and impeachable by the National Legislature. While he unequivocally supported some means of Executive disposal, legislative removal was questionable if the Legislature had a part in Executive appointment.

James Madison and James Wilson reflected their general preference for popular government rather than federal majorities when they pointed out that a majority of States calling for executive removal could easily mean a minority of people represented. Overall, they thought State participation in impeachment was bad policy. Today, we can see that Madison/Wilson’s views prevail. Since the foundation of Congress went fully popular with the 17th Amendment, the impeachment and conviction of high administration officials doesn’t depend on high crimes or misdemeanors at all; they shamefully depend on the President’s popularity polls.

All states except DE rejected Mr. Dickinson’s motion that the “Executive be removable by the National Legislature on request by a majority of the states.”

Instead ,Hugh Williamson (NC) motioned and the committee passed: “And to be removable on impeachment & conviction of malpractice or neglect of duty.” Thankfully, these terms did not make the final cut. Instead, much later on, delegates determined only crimes against the Constitution itself were worthy of removal from office.

Keep the States – Check the Executive. In his speech, Dickinson argued that a firm executive office could exist outside limited Monarchy, and was safely possible in a republic. Now, in the British government, the weight of the Executive arose from the political attachments which the Crown drew to itself, and not merely from the force of its prerogatives. In place of these attachments an American republic must look for something else. One source of stability was the double branch of the Legislature. Since a Senate of the States had yet to make its way into the Constitution, Dickinson expressed hope for a second legislative branch as stable as the Brit House of Lords. The division of the country into distinct States formed the other principal source of stability. This division ought therefore to be maintained, and considerable powers left with the States, especially as a check on the Executive (my words and italics).

Lessons of History. If ancient republics were found to flourish for a moment and then vanish forever, Dickinson said it only proves that they were badly constituted and that we ought to find remedies for their diseases. I say the Framers did just that, and it is to our shame that Americans since 1913 have not recognized the folly of the 17th Amendment and its negative impact on lawmaking, the Judiciary and the Presidency.

Among the take-aways from today’s proceedings is the Framers’ careful consideration of electors to the executive office. While all power flows from the people, they are not, as a group, qualified to judge the character and ability of men outside their local area.

Much depends on the duty and character of the office itself. Was the president to merely execute the law? If so, state legislative appointment of an experienced business CEO with experience in the law would probably suffice. But what if the Framers envisioned a higher place? If their executive was the face of the nation, the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, the man who led the nation in foreign affairs, who nominated judges, ambassadors, and had a limited veto over congressional bills, then his office should have a foundation on the people. Such an executive, when he occasionally goes toe-to-toe with Congress or other nations will need support, and that is best derived from the people themselves.

The motion as to the number of supreme Executives was postponed

In closing, a vote was taken to limit the President to one term, which passed 7-2-1.

- Franklin – “Besides these evils, Sir, tho’ we may set out in the beginning with moderate salaries, we shall find that such will not be of long continuance. Reasons will never be wanting for proposed augmentations. And there will always be a party for giving more to the rulers, that the rulers may be able in return to give more to them. “The more the people are discontented with the oppression of taxes; the greater need the prince has of money to distribute among his partisans and pay the troops that are to suppress all resistance, and enable him to plunder at pleasure.”

2. Just ask Donald Trump.

***

Shaping the Electoral College, Part IV

by Rodney Dodsworth August 15, 2019

Benjamin Franklin – “The first man at the helm will be a good one.”

June 4th, 1787.

The road to the Framers’ Electoral College was . . . arduous. At the open of today’s business, again in the committee-of-the-whole, one man would hold the executive office, be elected by the House of Representatives, and would remain in office for one seven-year term. His duty was to execute the law and the executive powers granted to Congress in the Articles of Confederation.

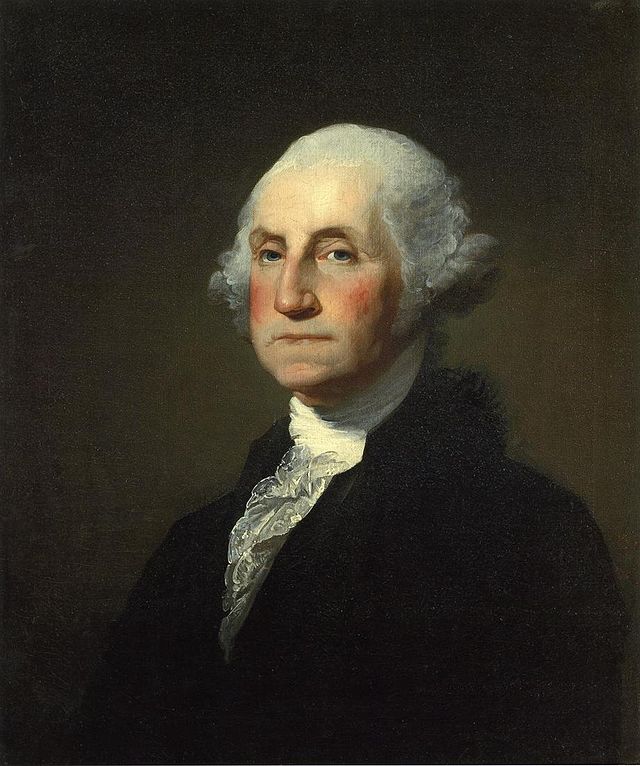

One and all knew perfectly well who was to be the first good man in the executive office. We cannot measure the influence and commanding presence of the most famous and trusted George Washington. Delegate Pierce Butler (SC) later wrote to a friend that the powers of the President “are full great, and greater than I was disposed to make them. Nor do I believe they would have been so great had not many of the members cast their eyes towards General Washington as President.” The American Presidency was made for men like George Washington and Donald Trump.

Ultimately, how was the American executive to be not only strong and energetic like the British Monarch, but also be safe for liberty? Our Framers admired the British system. While it would not do for Americans, the powers of Parliament and King hovered over the delegates. After the Convention, Luther Martin (MD) remarked, “We were eternally troubled with arguments and precedents from the British government.”

James Wilson (PA) provided a partial answer to checking the power of a single chief Executive. The recent experience among the thirteen states was that powerful legislatures will roll the Executive. He thus supported an absolute negative, with no override by the legislature.

In opposition, Benjamin Franklin related how the absolute veto in PA fostered incredible public corruption, even at the expense of scalped frontier settlers. Pennsylvania colonial Governors constantly used the veto to extort money. No good law could be passed without a private bargain with him. An increase of his salary, or some donation, was always a condition until at last it became the regular practice to have orders in his favor on the Treasury, presented along with the bills to be signed, so that he might actually receive the former before he should sign the latter. Roger Sherman (CN) also disapproved of the executive veto. Why should a single man be empowered to absolutely overturn the will of the whole?

Pierce Butler (SC) had been in favor of a single Executive Magistrate, but not when armed with an absolute negative over the law. He observed that the Executive power was growing in all the countries of Europe. Gentlemen seemed to think that we had nothing to apprehend from an abuse of the Executive power. But why might not a Cataline or a Cromwell arise in this country?

Judge Gunning Bedford (DE) and George Mason (VA) also opposed Executive checks over the legislative. Experience, per Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania proved the danger. Rather than institute a veto over the representatives of the people, why not enumerate the legislative powers of Congress? The Representatives of the people were the best judges of their interest, and ought to be under no external control whatever. In this framework there was no need for the veto.

Mason related further abuse of the veto. The Executive may refuse his assent to necessary measures until he gets the appointments he wants, and having by degrees engrossed all these into his own hands, the American Executive, like the British, will by bribery and influence save himself the trouble & odium of exerting his negative afterwards. We are not indeed constituting a British Government, but a more dangerous monarchy, an elective one. We are introducing a new principle into our system, and not necessary as in the British Government where the Executive has greater rights to defend. Do gentlemen mean to pave the way to hereditary monarchy? Do they flatter themselves that the people will ever consent to such an innovation?

The people never will consent to this executive power. Notwithstanding the oppressions and injustice experienced among us from democracy, the genius of the people is in favor of it, and the genius of the people must be consulted. Mason hoped that nothing like a monarchy would ever be attempted in this country. A hatred to its oppressions had carried the people through the late Revolution. Will it not be enough to enable the Executive to suspend offensive laws, until they are coolly revised, and the objections to them overruled by a greater majority than was required in the first instance? He never could agree to give up all the rights of the people to a single Magistrate. If more than one had been fixed on, greater powers might have been entrusted to the Executive. He hoped this attempt to give such powers would have its weight hereafter as an argument for increasing the number of Executives.

James Madison (VA) provided a compromise solution in a qualified legislative override. It was against the temper of Americans to grant monarchal powers to the Executive. His motion for a legislative 2/3 veto override passed.

Delegates then defeated the judicial veto of Congressional bills.

Like every other delegate, Franklin knew the first man at the helm would be a good one, but unless they devised an adequate electoral system, the Executive power would certainly increase, as elsewhere, until it ended in monarchy.

***

Shaping the Electoral College, Part V

by Rodney Dodsworth Auguat 16, 2019

June 9, 1787

Our Framers were not about to substitute one national tyrant with another. All had lived under the abuses of George III and his royal governors. Less well-known today is the 1776 reaction by the newly independent States. In an 18th century version of “power to the people,” the States set up overly democratic governments featuring weak governors. Although the rules varied from State to State, most legislatures appointed governors, made judicial appointments, and even served a judicial roles in some cases. Property wasn’t secure as the legislatures ran from one extreme to another according to the passions of the day. They violated wholesale Charles De Montesquieu’s admonition against combining legislative and executive power.June 9th, 1787.

So, Americans had suffered under strong executives and suffered under weak ones; they wanted neither. They sought a balance in which power was properly divided among branches, each with their own rights and prerogatives, such that no man or group of men could rule by fiat.

As opposed to the headless Articles of Confederation, the ideal administrator in our new republic was powerful enough to check legislative mistreatment, yet was sufficiently limited in his own powers. Furthermore, per Montesquieu, this man must not be the tool of any institution, faction, or collection of factions which we know today as political parties. The American President was independent of the other branches, but not isolated from them.

We cannot overstate the Framer’s efforts to avoid the executive abuses of George III as well as the democratic abuses of overly popular government. The chief executive must depend on the foundation of all republics, the people, yet not be so beholden to them that he and the office descend into tyranny.

On June 9th, the Committee of the Whole returned to executive elections. Since the goal was to provide an endless succession of men equal to George Washington, delegates sought an electoral method that identified and appointed such men. Why not rely on the judgement of other chief officers to identify in others the requisite traits in public virtue and leadership?

Elbridge Gerry (MA) proposed executive election by the State governors in proportion to each State’s representation in the Senate. At this point in the proceedings Senate membership was proportioned, like the House, according to population. There’s also been a shift in thinking of the chief executive away from his mere duty to execute the law. Unlike the English monarch, he wasn’t to be the heart and soul of the nation, but perhaps he should be its face, the man other nations regarded and respected as the limited leader of a free people.

So, instead of a tight connection with the authors of the law per the Virginia Plan, Gerry moved to establish an executor independent of Congress. He described election by governors as analogous to the principle observed in electing the other branches of the national government: the first branch being chosen by the people of the States, and the second by State legislatures. He did not discern any objection to this method and supposed the governors would select fit men for the office. Afterward, it would be their interest to support the man of their own choice.

While Gerry’s chief executive was not a tool of Congress, Virginia Governor Edmund Randolph opposed State governors as electors because the chief executive would lack the confidence of the people. Furthermore, expect State governors to select a man from amongst themselves, meaning covert side deals and corruption. He doubted the election ever of men from small States, and wasn’t confident in the governor’s familiarity with men outside their States. Finally, governors are very close to their legislatures, and would likely direct their governor’s vote for a national chief executive.

A national Executive thus chosen would not likely defend with vigilance & firmness the national rights against State encroachments. He did not envision that governors would feel the interest in supporting the national Executive which had been imagined. As Randolph put it, “They will not cherish the great oak which is to reduce them to paltry shrubs.”

Gerry’s motion for governors as executive electors was defeated, 10-0-1.

Delegates had so far considered and rejected elections by the people, the House of Representatives, Congress, State Legislatures, Governors, and through temporary electors from special districts. All except one method shared a fatal deficiency: sitting Presidents beholden to men with interests too narrow for the man who was to represent the American republic.

***

|

Shaping the Electoral College, Part VIby Rodney Dodsworth, August 22, 2019 July 17th and 19th, 1787. No other topic at the Federal Convention, our Article II chief Executive, demanded more time and debate. Our Framers needed some sixty votes to arrive at their brilliant Electoral College. Unlike the politics of redesigning Congress, the chief Executive emerged not from the clash of wills between large and small States, but from a series of ingenious efforts to design a new institution suitably energetic but safely republican. From the beginning to the end of the convention, delegates wrestled with Executive powers, the balance of those powers with Congress, and how a free people could design an office that prevented the trappings of monarchy, minimized internal and external corruption, promoted men like George Washington. Having survived the day before a near breakup and dissolution over equality of State representation in the Senate, delegates returned to the Executive branch, this time meeting in Convention.1 It was time to thrash through the recommendations of the committee-of-the-whole, and we’ll see over the next few days a schizophrenic quality to the proceedings. Delegates bounced back and forth between weak chief Executives dominated by Congress and strong Executives independent of Congress. Ditto for term length and re-eligibility for office. A weak Executive, a simple administrator of the law, could be trusted for much longer terms, perhaps even for life on condition of good behavior, than a strong Executive with a veto power over congressional bills, military duties, and influence over judicial appointments and treaties. • If the Executive was appointed by Congress, expect a creature of Congress. Notice that four States voted for an Executive-for-life, and only two voted in favor of State-appointed electors. Such was the discomfort and disorientation. 19 July 1787. As delegates continued to chase their tails on July 19th, we’ll see that Alexander Hamilton doesn’t deserve the modern opprobrium as the sole “monarchist” at the convention. No matter one’s views today, delegates in 1787 respected the English monarchy as an institution. English kings were above faction. They were not political party leaders and as such put the welfare of their kingdom ahead of narrow interests. Being hereditary, they were motivated to bequeath a peaceful, prosperous, and happy kingdom to their heirs. What would motivate American Presidents with short terms to leave behind a happy republic? This is why delegates had difficulty deciding between short v. long, and single v. multiple terms of office. A man limited to a single, short term, could hardly be expected to work in the long-term interests of the nation if the next guy could as easily undo his work. In time, the office could easily become one of personal enrichment. On the other hand, if he was popularly re-electable, the people would regularly judge his performance and thus join his interests with those of the nation. Or would they? Are the people trustworthy? But . . . if Congress appointed him, multiple-term Executives would coddle Congressional favor by rubber-stamping legislation and offering lucrative Executive branch jobs to Congressmen’s family and friends. The national interest of this President couldn’t possibly figure high on his list of priorities. This institution invited factional chief Executives. The Convention toyed briefly with a President for life conditioned on good behavior. A weak Executive over a nation stretching perhaps from sea to sea and with dozens more States just wouldn’t do. No matter the mode of election, either popular or by Congress, a lifelong chief Executive could focus, like the ideal monarch, on the good of the American republic without answering to political debts in his continual efforts to secure reelection. Gouverneur Morris shared his thoughts as to what he expected of a proper “Executive Magistrate.” It is necessary that he should be the guardian of the people against legislative tyranny, against the great and the wealthy who in the course of things will occupy Congress. Wealth tends to corrupt the mind and nourish its love of power, and stimulates it to oppression. History, he said, “proves this to be the spirit of the opulent.” The check provided by the Senate over the House was not meant as a check on legislative usurpations of power, but on the abuse of lawful powers, on the propensity in the House to legislate too much to run into projects of paper money & similar expedients.2 A Senate of the States isn’t a check on legislative tyranny. On the contrary it may favor tyranny, and if the House can be seduced, it may find the means of success. The Executive therefore ought to be so constituted as to be the great protector of the people. Morris also disfavored impeachment and removal of a Congressionally appointed life-long Executive Magistrate because it will constitute a threatening sword over the Executive’s head during the inevitable policy disputes. Morris: “It will hold him in such dependence that he will be no check on the legislature, will not be a firm guardian of the people and of the public interest. He will be the tool of a faction, of some leading demagogue in the legislature.” Morris saw no alternative for making the Executive independent of the legislature but either to give him his office for life by the legislature, or make him re-electable every two years by the people themselves. Since a President for life smacked of monarchy, and the people weren’t trusted in direct elections, the Convention, slowly, by degrees, was reasoning itself toward an electoral form that avoided dependence on Congress as well as an uninformed public. Some sort of intermediate electors independent of the people and Congress would do the trick. Shall the Executive be appointed by electors? Yes, 6-3. Adjourned. 1. Connecticut Compromise – Equal State representation passed by a bare 5-4-1 on July 16th. A very close call. Delaware’s Paterson was so angry during the debate he offered to second any motion for the convention to adjourn sine die. Rakove, J. N. (1996). Original Meanings – Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution. New York : Random House. 80. |

***

Shaping the Electoral College, Part VII

By Rodney Dodsworth, August 26, 2019

July 20th, 1787.

Since the delegates in Convention determined yesterday that State legislatures would appoint electors to the Executive office, the next logical question was, “how many?” Elbridge Gerry (MA) motioned a starting point, an initial number of electors per state for the first election and suggested, NH 1, MA 3, RI 1, CN 2, NY 2, NJ 2, PA 3, DE 1, MD 2, VA 3, NC 2, SC 2, GA 1.

Notice the semi-federal nature of Gerry’s electoral vote allotment. Yes, more populous States had more electors, but their allotment nowhere near approximated the existing population ratio amongst the States. Now, maybe I’m making something out of nothing, but George Washington was going to be the first Chief Executive no matter the allotment of Electoral College votes. Perhaps delegates reasoned the same way. With little debate they carried Gerry’s motion as to the number of electors, chosen by state legislatures, in the first election, 6-4.

A portion of the 9th Resolution, “to be removable on impeachment and conviction of malpractice or neglect of duty,” was next.

While we take Presidential impeachment for high crimes and misdemeanors by the House and trial by the Senate for granted today, it was a troubling issue at the Convention that impacted, and was in turn impacted by who or what body appointed the President, his term length, and relationship to the other branches. Would future Congresses convict and remove the Chief Executive over policy differences? Gouverneur Morris (PA) thought so, which is why he would render the Executive un-impeachable, like the British Monarch and for the same reason. Instead, Congress could impeach and remove executive branch ministers, just as Parliament sometimes did with the King’s advisers. Besides, if he was limited to short terms of office, why put the nation through the trouble?

On the other hand, Benjamin Franklin viewed impeachment and removal as a necessary check on the occasional rogue President. Impeachment, while wrenching to the nation, wasn’t violent. Provide a peaceful alternative to violence and assassination. Also, since impeachment by legislative bodies stood for a grand jury, they were available to acquit an innocent man as well.1

Madison elaborated justification for impeachment to include incapacity, negligence, perfidy, perversion of his administration, peculation, oppression, and betrayal. What if, like King Charles II of the UK, the President took a foreign government salary? Certainly, no matter who or what body appoints him, there must be some ultimate check on his behavior.

As Elbridge Gerry (MA) succinctly put the matter, a good magistrate will not fear impeachment. A bad one ought to be kept in fear of them. This Magistrate is not the King but the prime-Minister. The people are the King.

On the question, “Shall the Executive be removable on impeachment and conviction of malpractice or neglect of duty,” passed 8-2.

Next, the Convention agreed unanimously “that the Electors of the Executive shall not be members of the Natl. Legislature, nor officers of the United States, nor shall the Electors themselves be eligible to the supreme magistracy.” At every possibility, delegates wrote anti-corruption clauses into the Constitution.

James McClurg (VA) queried as to the powers of the Executive. The committee of detail would have an easier time in their work if they had direction as to the extent/limits of Executive power.

Near this midpoint in the convention we see the outlines of government: three branches, electors to the branches, and some mutual checks. But, what about the nuts and bolts limits to their authority? In the UK, its unwritten Constitution was, as a practical matter, whatever Parliament said it was. That wouldn’t do for the Framers’ Constitution. So, the obvious answer was to shackle the Executive in his powers. But, the first man, Judge Gunning Bedford (DE), to noodle the best approach, the one in the finished Constitution, was instead to restrict Congress’ authority. Article I assigns limited legislative powers “herein granted,” while Articles II and III give the whole of Executive Power to a President, and the Judicial Power to a Supreme Court and inferior courts created by Congress. Brilliant!

Adjourned.

- In his Discourses on Livy,Niccolo’ Machiavelli praised the Grand Jury of republican Rome. The use to which Ben Franklin alluded was to identify and silence the source of destructive “whisper campaigns” that attacked and subverted the character of public men. See Book I, Chapter 8. In this way President Trump, to clear his name, should have immediately called for an impeachment inquiry of groundless and destructive “Russian Collusion” that sapped his public support.

***

Shaping the Electoral College, Part VIII

By Rodney Dodsworth, August 29, 2019

July 24th, 1787. More blind alleys.

Let the schizophrenia continue! A couple days ago, delegates passed the framework of what we’d recognize as the Electoral College. State legislatures appointed electors. The only remaining substantial question was “how many votes per state?” Well, that progress vanished today. To get an idea, here are my Cliff Notes to the day’s proceedings:

- Divide the nation into three electoral districts to select three executives.

• Fear an elected Monarch.

• Electors equal in number to the State’s Congressional delegation was resoundingly defeated.

• Return to Congressional appointment by 7-4 vote.

• Executive must be independent of Congress after the election. A single twenty year term?

• To prevent intrigue, draw fifteen Congressmen by lot to immediately vote and elect an Executive.

It is worthwhile, while we are down here in the weeds, not to forget that the central purpose of the Framers’ electoral system was to provide an endless succession of men like George Washington, men of unsurpassed public virtue and executive ability. To this end, we haven’t seen recent motions to popularly elect the chief Executive . While the people of the time would certainly have elected Washington, there was no telling what sort of demagogues a duped people would fall for in the future. The American President wasn’t to be the tool of any faction, political party, state governors, or branch of government. As Gouverneur Morris warned today, “Original vice here could not be corrected.” The Framers had to get it right. They did.

In Convention, the appointment of Executive Electors resumed.

Gouverneur Morris (PA) – Of all possible modes of appointment, that by Congress is the worst. If the Congress is to appoint, and to impeach or to influence the impeachment, the Executive will be the mere creature of it. Only a few days earlier, Morris was opposed to impeachment but was now convinced the Constitution must provide for impeachment if the appointment was to be of any extended duration. No man would say that an Executive known to be in the pay of a foreign power should not be removeable in some way or another.

Some delegates found Morris inconsistent regarding his trust in legislatures. He explained that legislatures are worthy of unbounded confidence in some respects, and liable to equal distrust in others. When their interest coincides precisely with that of their constituents, as happens in many of their Acts, no abuse of trust is to be apprehended.

But when a strong personal interest opposes the general interest, no legislature is trustworthy. In all public bodies there are two parties. The Executive will necessarily be more connected with one than with the other. There will be a personal interest therefore in one of the parties to oppose as well as in the other to support him. Much had been said of the intrigues that will be practiced by the Executive to get into office. Nothing had been said on the other side of the intrigues to get him out of office. Some party leader will always covet his seat, will perplex his administration, will cabal with the Legislature, till he succeeds in ousting him.

If the delegates to this Convention did not provide a good organization of the Executive, he doubted whether we should not have something worse than a limited Monarchy. To avoid dependence of the Executive on the Legislature, the expedient of making him ineligible to a second term had been devised. This was as much as to say we should give him the benefit of experience, and then deprive ourselves of the use of it.

But make him ineligible a second time and extend his term to say, fifteen years; will all the men to this office reliably step down? No. If just one is unwilling to quit “the road to his object through the Constitution,” he will have the sword, a civil war will ensue, and the Commander of the victorious army on whichever side, will be the despot of America.

This consideration renders him particularly anxious that the Executive should be properly constituted. The vice here would not, as in some other parts of the system, be curable. It is the most difficult of all rightly to balance the Executive. Make him too weak, and Congress will usurp his powers: Make him too strong, and he will usurp Congress. He preferred short terms and re-eligibility, but a different mode of election.

Furthermore, and with an eye on ratification, the Constitution was doomed if the people sniffed out an infant Monarch. Morris would vote against any such plan of extended Presidential terms.

And as for James Wilson’s suggestion – draw fifteen Congressmen by lot to immediately vote and elect an Executive, Morris found this method safer than the intrigue and corruption certain to accompany Congressional elections.

Adjourned.

***

| Shaping the Electoral College, Part IX

By Rodney Dodsworth, September 2, 2019 July 25th, 1787. Despite trodding familiar ground once again, we can see today the Framers’ determination to craft a corruption-free mode of election such that new Presidents could faithfully execute their duties. The Framers’ President wasn’t the leader or product of a political party. Nor was he in the pocket of foreign interests. James Madison opened with a review of the four possible modes of Executive election: by the National or State authorities, electors chosen by the people, or the people themselves. From the Framers’ widespread experience in State government, no one raised an eyebrow when he criticized Executive election by the House of Representatives or Congress. Expect in every election a conspiratorial mess. Any President appointed in this fashion was pre-bought, if not fatally weakened by the side-deals and self-serving promises among members. He predicted occasional fisticuffs and violence. This process burdened the outcome, a President, in such a way that he doubted that Presidents could defend the general welfare of the nation. What about foreign influence in Congressional Presidential elections? Congress was small enough to practically invite bribes from foreign ministers. Madison’s disgust with State governments ran deep. The States were not held in high esteem thanks to their conduct under the Articles of Confederation. It is fair to say their poor behavior and disregard of the Articles necessitated the Philadelphia Convention in the first place. Thanks to the State Legislatures’ regular propensity to “a variety of pernicious measures,” their participation in Presidential elections went nowhere. Election by State Governors was fraught with problems as well. As with election by Congress, expect intense intrigue among Governors. Governors could hardly avoid not electing one of their own in a fashion described by Madison as “a College of Cardinals.” These conclusions left the remainders, either direct or indirect election by the people. Madison supported the direct mode of election by the people above all others. In direct elections, he noted that small states would be at an admitted disadvantage to see the election of their favorite sons. This is the first reference I’ve seen to large v. small states regarding presidential elections. To placate the small State contingent, Gouverneur Morris suggested each elector vote for two candidates; one of whom was not from his home State. In this imbroglio, that of large v. small States, the Framers wandered from the purpose of Presidential elections. WHERE the President was from dimmed to the point of irrelevance compared TO WHOM the President was responsible. Judge Oliver Ellsworth (CN) attempted to answer Madison’s objections regarding Congressionally-dependent Presidents. Let Congress elect the Executive to his first term. If he ran for reelection, State Legislatures would do the electing. Thus, his continuance in office would not depend on the National Legislature after his first election. Nonetheless, Elbridge Gerry (MA) insisted that election by the National Legislature was fatally flawed. Leave it entirely to State Governors or State Legislatures. Charles Pinckney (SC) still supported election by the National Legislature such that no man be eligible more than six years in any twelve. This rule would reduce the disadvantage of letting talented men go, for they could return to service.1 George Mason (VA) and Pierce Butler (SC) feared cabal at home and influence from abroad. They were nearly unavoidable. Popular nationwide elections would be unwieldy and complex. Butler preferred Electors appointed by the State Legislatures. Each State should have an equal number of votes, with no proportionality by population. How about THAT? Truly federal elections. This idea found its way into Article II. In the typical election, one in which State electors do not produce a majority winner, the House of Representatives immediately votes, with one vote per State delegation. Elbridge Gerry (MA) termed popular election “radically vicious.” He was certain that the Order of Cincinnati would lead ignorant people astray.2 John Dickinson (DE) noted the insuperable objections against Executive election by the National or State Legislatures and State Governors. Direct election by the people was the purest mode and had the fewest objections. Partiality to favorite sons was a problem he would minimize by having popular nomination in each State of one Candidate. From this list, the National Legislature selects a National Executive. While they reasoned from different directions, the Framers are talking themselves into the finished form of their Electoral College, in which the House of Representatives was often expected to ultimately elect the President. Today’s summary: • Four choices: By National or State authorities, electors chosen by the people, or direct popular election. 1. Republican Rome limited their consuls to one annual term every ten years. |

***

Shaping the Electoral College, Part X

By Rodney Dodsworth, Sept 5, 2019

July 26th, 1787 – Back to Square One.

“We are,” James Wilson reminded delegates, “providing a constitution for future generations, and not merely for the peculiar circumstances of the moment.”

Colonel George Mason (VA) reviewed the modes of Executive election. None of them were entirely satisfactory. Several retained elements of popular election.

- By the people, which he ridiculed in saying “that an act which ought to be performed by those who know the most of eminent characters, and qualifications, should be performed by those who know the least. “

2. By the State Legislatures or State Governors. Both invited unacceptable cabal and intrigue.

3. Election by Electors chosen by the people was at first agreed to, but was subsequently rejected.

4. Similarly, the Convention declined a popular election franchise limited to landowners, to freeholders, each of whom would vote for several candidates. This approach appeared plausible, but on closer inspection was liable to fatal objections. A popular election in any form would throw the appointment into the hands of the Cincinnati, a Society for the members of which Mason had great respect; but which he never wished to have a preponderating influence in the government.1

5. By the people, with proviso to not vote for a favorite State son. This was a nod to the small states over fears of large state dominance.

6. By Congressional lottery. With additional snark, Mason noticed little demand for the tickets.

7. By Congress.

After reviewing the various methods, he concluded that election by Congress as originally proposed was the best. While it was liable to objections, it was liable to fewer than any other. To minimize congressional post-election influence over the executive, he envisioned single terms. Having for his primary object, for the pole-star of his political conduct, the preservation of the rights of the people, he held it as an essential point, as the very palladium of civil liberty, that the great officers of State, and particularly the Executive should at fixed periods return to that mass from which they were at first taken, in order that they may feel & respect those rights and interests, which are again to be personally valuable to them. He concluded with moving that the Constitution of the Executive as reported by the Committee-of-the-Whole be re-instated, viz. “that the Executive be appointed for seven years, & be ineligible a 2d. time”

Gouverneur Morris was now against the whole paragraph. In answer to Col. Mason’s position that a periodical return of the great officers of the State into the mass of the people, was the palladium of civil liberty he observed no such motions to term limit Congressmen, Senators or Judges.

On the question on the whole resolution as amended in the words following- “that a National Executive be instituted-to consist of a single person-to be chosen by the National Legislature for the term of seven years, to be ineligible a second time, with power to carry into execution the National laws, to appoint to offices in cases not otherwise provided for, to be removable on impeachment & conviction of malpractice or neglect of duty, to receive a fixed compensation for the devotion of his time to the public service, to be paid out of the National treasury,” – it passed in the affirmative.

NH aye, MA not on the floor, CN aye, NJ aye, PA no, DE no, MD no. VA divd, NC aye, SC aye, GA aye.

The logic around the resolution for legislative appointment of a one term, seven year president was that popular election was risky and some filter in Presidential selection was prudent. Most State Governors were appointed by, and were subservient to, their legislatures, so why not the President? Well, weak State executives were a response to our revolt against England, where a powerful King made war on his subjects. While the legislative mode of selection was acceptable at the National level, an executive as weak as most State Governors was not. The answer at this point was to retain legislative election, but isolate his performance from the influence and machinations of Congress. That is why the Framers went for a single term of reasonable length. With a single term, the President would not have to constantly look over his shoulder at Congress or allow it to influence his decisions.

For readers today who chuckle at the notion of legislative appointment as a silly diversion from the final form of the Electoral College . . . not so fast. A modified form of legislative appointment made the final cut in our Constitution, in which the House of Representatives, voting federally, was expected to have the final say in most Presidential election outcomes.

Notice also the power to impeach, convict and remove the President from office. That peaceful avenue to seek relief from oppression, to impeach and remove the King of England was not available to the American Colonists. It just did not exist in a legal system designed to secure the prerogatives of the Crown. So, our Framers provided nonviolent means of relief. Instead of revolt, instead of storming the White House to behead the President and his family, we expected to peacefully remove rogue Presidents.

Back to square one; Congress elects a single executive to one seven year term, passed 6-3.

The Convention adjourned to Monday, August 6th, to give the Committee of Detail time to put the VA Plan, as modified by the various resolutions passed over the summer, into a smooth form.2

- Society of the Cincinnati.

2. John Rutledge chaired the committee. The other members were Edmund Randolph, Oliver Ellsworth, James Wilson, and Nathaniel Gorham. Rutledge was a Revolutionary War governor of SC, while Randolph was the sitting governor of VA.

***

Shaping the Electoral College, Part XI

By Rodney Dodsworth, Sept 9, 2019

In Convention August 24th, 1787 – His Excellency, the President of the United States of America.

Today’s Summary:

- First formal use of “President.”

• Single seven year term.

• Elected by Congress, by joint session or by each house separately?

• By joint session, which threw dominance to large States, passed 7-4.

• One vote per State? No, by 6-5 vote.

• Corruption & intrigue w/Congressional election.

• Popular vote to appoint electors narrowly failed, 6-5.

From the Committee of Style’s August 6th report, “The executive power of the U. S. shall be vested in a single person. His stile shall be “The President of the U. S. of America” and his title shall be “His Excellency.” He shall be elected by ballot by the Legislature. He shall hold his office during the term of seven years; but shall not be elected a second time.”

So far, delegates accepted a tradeoff in the mode of electing this new guy to history, the President of the United States. In legislative appointment they expected cabal and intrigue. Imagine the scene, even prior to the 17th Amendment of 1913, of Congressmen and Senators, led by the majority and minority leaders, cajoling and offering side deals along the way of appointing a President! Did the Framers really believe the outcome of this behind the scenes plotting, a creature of Congress, could actually arrive in office without political debts and take the oath of office with a clear conscience?

Despite the unsaid and hidden quid-pro-quos around the neck of every President upon inauguration, delegates reasoned that due to their single, seven year terms, Presidents would hopefully double-cross their benefactors in Congress, and actually perform their duties without regard to pre-election promises. Politics never was a game of beanbag anywhere, but this method practically invited fisticuffs on the floor of Congress.

Now, was the election to be by each house of Congress or in joint session? In the interests of the small States, Roger Sherman (CN) objected to election in joint session. Separate approvals from each house would protect small State interests. Nathaniel Gorham (MA) asked members not to forget their first purpose: the public good. Great delay and confusion would ensue if the two Houses should vote separately, each having a negative on the choice of the other. Imagine the turmoil if one branch of government could shut down and effectively do away with another branch!

Populists saw their opportunity and motioned to strike out “by the Legislature” and insert “by the people.” No such luck. It went down in flames with only PA and DE in the affirmative.

James Wilson (PA) argued the reasonableness of joint session elections, of allowing the larger States a greater voice. Along with John Langdon (NH – former governor), who admitted the disadvantage to smaller States of a joint ballot, still believed it was the most prudent approach. In New Hampshire, the two legislative houses voted separately for governor. It was the source of “great difficulties.”1

Wilson anticipated another problem with the houses voting separately. Since the Senate elected its own President, count on these powerful men to extort Congress into electing themselves to the Presidency.

The convention approved election by joint session 7-4.

Jonathan Dayton (NJ) motioned voting by State delegation, rather than by individual Congressmen and Senators. His proposal to change the clause to “He shall be elected by ballot by the Legislature, each State having one vote,” went down 6-5. Recall this nearly identical phrase in the final draft, which exists to this day in the Constitution in the event no person wins a majority in the Electoral College. But instead of voting by State in joint session, each delegation in the House of Representatives has one vote.

Gouverneur Morris predicted disastrous outcomes from Congressional elections. Despite single terms, he expected he President of the Senate to work in a symbiotic, self-serving fashion with the nation’s chief Executive. In this relationship, one in which the interests of the nation are a distant second-place, the two men will conspire and intrigue to perpetuate their own power and wealth, as well as that of family, friends and accomplices. Morris foresaw legislative tyranny. Its remedy was to amend the clause to read, “he shall be chosen by Electors to be chosen by the People of the several States.”

Morris’ motion was seconded, and went down to defeat 6-5. The votes today exposed the delegates’ underwhelming support for Congressional elections. The Convention half-heartedly accepted a close Congress/President arrangement that terribly muddied separation of powers.

Next, the Convention considered the powers of this Congressionally-dependent President. As one can imagine, having decided the method of election, delegates could fill in the President’s powers. While not addressed here in detail, they reveal the familiar scope of his authority in the final draft Constitution.

The President shall:

- Present to the Legislature, information as to the state of the Union. He may recommend to their consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient.

• Convene the Legislature on extraordinary occasions. In case of disagreement between the two Houses, with regard to the time of adjournment, he may adjourn them to such time as he thinks proper.

• Duly and faithfully execute the laws of the United States.

• Commission all the officers of the United States; and shall appoint officers in all cases not otherwise provided for by this Constitution.

• Receive Ambassadors, and may correspond with the supreme Executives of the several States.

• Have the power to grant reprieves and pardons; but his pardon shall not be pleadable in bar of an impeachment.

• Be commander in chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States.

• At stated times, receive for his services, a compensation, which shall neither be increased nor diminished during his continuance in office.

• Take the following oath or affirmation, “I – solemnly swear, (or affirm) that that I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States of America.”

• Be removed from his office on impeachment by the House of Representatives, and conviction in the supreme Court, of treason, bribery, or corruption.

Adjourned.

- On January 5th 1776, New Hampshire was the first state to adopt a formal constitution. Under this constitution, in effect until 1784, there was no established executive, and the legislature was supreme.

***

Shaping the Electoral College, Part XII

By Rodney Dodsworth, Sept 12, 2019

September 4th, 1787

David Brearley (NJ) delivered another partial report from the Committee of Eleven, which was established on August 31st. Composed of one delegate from each state, the committee considered postponed clauses.1 After addressing Congressional authority over foreign and interstate commerce, the Convention once again visited Presidential elections. There was only one problem. The Committee of Eleven wasn’t charged with reconsidering the mode of electing the President. Oops. Before the Committee’s revision, Congress was to elect the President to one seven-year term:

The executive power of the U. S. shall be vested in a single person. His stile shall be “The President of the U. S. of America” and his title shall be “His Excellency.” He shall be elected by ballot by the Legislature. He shall hold his office during the term of seven years; but shall not be elected a second time.

So, in the hope of finding forgiveness rather than permission, the Committee recommended four-year Presidential terms, and created the office of Vice President along with his duties in the Senate. Most importantly, it endorsed our familiar electoral college, with State-derived electors allocated on Congressional representation. The major difference with the final draft coming in a few days, was that in the event of no majoritarian winner, the Senate (rather than the House of Representatives) was to immediately appoint the President from the top five contenders.

Governor Randolph (VA) and Charles Pinkney (SC) asked for an explanation as to why the committee overstepped its boundaries. Committee members Roger Sherman (CN) and Gouverneur Morris explained that one purpose was to allow for multiple, but shorter terms. Another was to make the President less dependent on the Legislature. Morris gave clear and compelling reasons to be rid of sole reliance on Congress, and move toward the States for Executive electors. This was old ground which one and all knew very well. Support for entirely Congressional elections was always thin, and had grown thinner once the delegates filled in the particular powers of each branch.

As a practical matter, the delegates envisioned a process in which either the state legislatures or the people of the states vote for upstanding, respected men in their communities to serve as Presidential electors. In a nod to the small States, each elector cast two votes, one of which had to be for someone from another State. Still, considering the population dominance of VA, PA, MA, our Framers expected most nominees would come from large States, with the actual election determined by the small body of US Senators, which favored small States.

There was one sticking point in particular that required attention: The same men who voted individually for the President also sat as jurors in impeachment trials.

James Wilson summarized the electoral issue. The election, composition and powers of the chief magistrate for the nation was a difficult matter that greatly divided the delegates. Whatever the Convention decides will arouse similar emotions and reflection among the public. While, in his opinion, none the electoral modes were entirely satisfactory, the plan on the table today was a valuable improvement on wholly Congressional elections with single-term Presidents. It removed the great evils of Congressional cabal and corruption, and anticipated that as the nation grew, well-informed electors would stand ready to use their judgement to nominate quality men to the Presidential office. Also, it also cleared the way for re-election of qualified men of proven performance, which the previous mode limited to one seven-year term.

Wilson suggested amendments. Since State electors would rarely nominate a clear majoritarian winner, he preferred the responsibility for eventual appointment to fall on the entire Congress rather than the Senate. Our Framers expected a tight, clubby Senate of the nation’s natural aristocracy and a wild House of Representatives of regularly rotating membership. Let the reps of the people participate. Also, limit Congress’ choices to fewer than the top five candidates, and structure the election to occur immediately (if no candidate won a majority) after the ballots are unsealed and read aloud in joint session of Congress. This eliminated the possibility of deal-making and corruption among Congressmen and Senators.

Overall, the Framers’ arrangement helped soothe the public’s fears of an aristocratically elected monarch disconnected from the people. In true republican fashion, have the States decide the mode of selecting electors and include the representatives of the people in the final selection of the President of the United States.

Despite the debate, there were no major Electoral decisions today. By 7-3 vote, further consideration of the Report was postponed to tomorrow, September 5th.

- Nicholas Gilman (NH), Rufus King (MA), Roger Sherman (CN), David Brearley (NJ), Gouverneur Morris (PA), John Dickinson (DE), Daniel Carrol (MD), James Madison (VA), Mr. Hugh Williamson (NC), Pierce Butler (SC), Abraham Baldwin (GA).

***

Shaping the Electoral College, Part XIII

By Rodney Dodsworth, Sept 16, 2019

September 5th, 1787—George Mason prefers the government of Prussia.

As we know, the Convention adjourned on September 17th and forwarded the draft Constitution to Congress. At this late stage, September 5th, delegates were rapidly filling-in the Constitution’s various powers and limits. It’s all the more amazing they still squirmed over how to elect a President. Tempers flared.

In their quest to craft a suitable presidential election mode, the delegates failed once again; they ended the day where they began:

The executive power of the U. S. shall be vested in a single person. His stile shall be “The President of the U. S. of America” and his title shall be “His Excellency.” He shall be elected by ballot by the Legislature. He shall hold his office during the term of seven years; but shall not be elected a second time.

Debate returned to the report from the Committee of Eleven, composed of one delegate from each state. The committee recommended unlimited four-year presidential terms, a Vice President to preside over the Senate, and an electoral college with state-derived electors allocated by Congressional representation. In the event of no majority winner in the electoral college, the Senate would immediately vote to appoint the president from among the top five nominees.

Charles Pinckney (SC) renewed his opposition to this mode of election, which would surely end up in the Senate almost every time. Considering the vice-president stood watch over the Senate, he feared a combined executive branch and Senate running roughshod over the House of Representatives. Others feared a quasi-aristocracy. Considering the already enormous power of this small body, starting with only twenty-six members, additional power over presidential elections was just too much to accept. Since thirteen members comprised a quorum to do business in the first Senate, a bare majority of only seven men could conceivably make Presidents!

George Mason (VA) agreed with Pinckney and predicted the near-certainty of reelection for sitting Presidents. Given the closeness between the Senate and a President, together they could subvert the Constitution. To avoid this, he motioned to strike “if such number be a majority of that of the electors” from the clause.

Instead he proposed, “The Person having the greatest number of votes shall be the President.” To keep presidential elections entirely out of the Senate and Congress, Mason proposed a plurality winner! We can only guess today at the possible ramifications of a plurality president. Would it spawn more than two significant political parties? Would the nation come to regard plurality v. majority presidents as less worthy of respect? Would it prevent the two subsequent major parties from corrupting the electoral college process?

We’ll never know, because despite neutralizing the problems involving senatorial elections, Mason’s motion failed big, 10-1.

For the rest of the day’s frustrating debates, delegates resumed old arguments and fears.

Wilson’s motion to empower the entire Congress with presidential elections failed 7-3-1.

Another motion to keep Congress out and allow plurality presidents failed 9-2.

Elbridge Gerry (MA) motioned six Senators and seven Congressmen be selected by joint ballot to elect the President.

Roger Sherman (CN), a very reasoned man who proposed what evolved into the Connecticut Compromise that established state equality in the Senate, threatened to walk out and give up the plan, the Constitution.

Mason let lose a blast. He “would prefer the Government of Prussia,” rather than accept the aristocratic plan in front of him.

VA Governor Edmund Randolph cast doubts on the entire draft Constitution when he expressed fear of an eventual monarchy working with an aristocratic Senate.

Whatever the final system, the small states must have some say, some measure of input to protect themselves. But James Wilson (PA) and James Madison (VA) fairly ignored the small state interest when they respectively proposed to replace the role of the Senate with the Congress, or perhaps with the mass of the people.

Despite today’s failures and discord, the Convention actually noodled its way toward a solution. Framing the discussion were a few accepted principles and requirements to help guide the delegates. To avoid an eventual monarchy, delegates considered and rejected service limited only by good behavior. To encourage the service of talented men, yet not risk monarchy, the convention decided on short, multiple terms.

Third, the president mustn’t be the tool of any standing body, a house of Congress, or the states. He must be responsible to the people yet not be like a weather-vane reacting to their every shifting passion. While it would appear that state-derived electors invited cabal and intrigue, delegates knew from experience the lack of coordination among the states under the Articles of Confederation, this was a remote possibility.

So far, while the Framers’ kept their electoral college uncorrupted, it was doubtful the isolated electors would independently elect a majoritarian winner. Convention delegates from large and small states alike accepted large state domination of the electoral college, in what they expected to be an institution that typically nominated candidates.

But, in the actual election, the small states demanded influence. While turning the election over to the Senate appeared to satisfy this requirement, the problems associated with that small, powerful, aristocratic body caused delegates to pause and reconsider. Again.

Adjourned.

***

Shaping the Electoral College, Part XIV

By Rodney Dodsworth, Sept 19, 2019

September 6th & 7th, 1787. Putting it all together.

With an eye on keeping separation of powers and preventing corruption of the executive branch, our Framers on September 6th 1787 put the finishing touches to Article II.

Rufus King and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts motioned that “no person shall be appointed an elector who is a member of the Legislature of the U. S. or who holds any office of profit or trust under the U. S.” It passed by acclamation. Was this precaution an overkill? Perhaps, but our Framers diligently prevented any semblance of the awful practice of the British system in which members of Parliament served in other salaried positions for the Crown, Judiciary, and Anglican Church.

Delegates still weren’t comfortable with senatorial election from the five highest nominees of the Electoral College. The Senate already had aristocratic trappings. Why make it the “king maker” just to quell small state fears? James Wilson foretold a “dangerous tendency to aristocracy; as throwing a dangerous power into the hands of the Senate. They will have in fact, the appointment of the President, and through his dependence on them, the virtual appointment to offices; among others the offices of the judiciary department. They are to make Treaties; and they are to try all impeachments.” As the plan stood, Wilson asserted “the President will not be the man of the people as he ought to be, but the minion of the Senate.” He went so far as to suggest senators will contrive to ensure all elections fall into their laps.

Roger Sherman (CN), perhaps best known for the Connecticut Compromise that saved the convention in July, said that while he would go along with the existing plan, he proposed an alternative. Why not empower the entire Congress, sitting and voting as states, to immediately vote for a President from the EC’s five top candidates? Presidents would assume office with the backing of the representatives of both the people and states. It was a solution the small state delegates could support.

Alexander Hamilton (NY), who said little since his day-long speech in June, supported a previous motion to appoint the majority or plurality winner of the EC. Since the Senate could make the nominee with the fewest number of EC votes the President, he saw no reason for objection.

His proposal went nowhere. The convention moved on to approve by large majorities an unlimited number of four year terms, and the assignment of state electors equal to the number of their legislators in Congress.

Next, delegates passed two seemingly innocuous resolutions we hardly notice today, but were essential to avoid cabal and intrigue. First, the electors would NOT meet in the US capital to cast their votes. This prevented influence and discussion among the electors. Instead, they would cast their votes, in their respective states, on the same day. Second, the recorded votes were sealed and sent to the President of the Senate. In this way, the results of the election weren’t known until the President of the Senate read the ballots aloud to a joint session of Congress. Once again, the convention headed-off backroom deals.

At this moment, so very late in the summer, the fatigued Framers still faced a critical question, “which body of Congress shall elect the President in the event of no majoritarian winner of the EC?” Delegate Hugh Williamson (NC) suggested the entire Congress, voting by state, and not per capita. Sherman immediately cut in to motion the House of Representatives, instead of the Senate or the entire Congress voting by state delegations, one vote per state. It passed 10-1.

George Mason (VA) who ultimately did not sign the Constitution because it leaned too far toward aristocratic government, appreciated Sherman’s amendment as lessening the aristocratic influence of the Senate.

Having established the workings of the EC and the likely election of the President by the House of Representatives voting by state, the Convention completed the essentials of Article II and would formally incorporate it into the Constitution tomorrow September 7th.

Adjourned.

To modern opponents of the Electoral College, the Framers’ system is an archaic holdover from less progressive times. They summarily dismiss it as anti-democratic 18th century nonsense put to paper by the same sort of people who oppress minorities to this day. Part of the misunderstanding of the EC is due to corruption of the system by the two major political parties. It is difficult to read this series and Article II without viewing them through the lens of political party distortions beginning with the choice of electors.

But, for readers with the will to imagine the absence of political party domination and exploitation, the Framers’ system was a beautiful foil to the first enemy of republics: factions. Factions are a republic’s worst enemy, and the soiled system we’ve come to accept, in which the people’s practical choice of electors is limited to one of two outright leaders of factional political parties, makes a mockery of our Framers’ efforts.