Shaping the Electoral College, Part XIV

By Rodney Dodsworth, Sept 19, 2019

September 6th & 7th, 1787. Putting it all together.

With an eye on keeping separation of powers and preventing corruption of the executive branch, our Framers on September 6th 1787 put the finishing touches to Article II.

Rufus King and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts motioned that “no person shall be appointed an elector who is a member of the Legislature of the U. S. or who holds any office of profit or trust under the U. S.” It passed by acclamation. Was this precaution an overkill? Perhaps, but our Framers diligently prevented any semblance of the awful practice of the British system in which members of Parliament served in other salaried positions for the Crown, Judiciary, and Anglican Church.

Delegates still weren’t comfortable with senatorial election from the five highest nominees of the Electoral College. The Senate already had aristocratic trappings. Why make it the “king maker” just to quell small state fears? James Wilson foretold a “dangerous tendency to aristocracy; as throwing a dangerous power into the hands of the Senate. They will have in fact, the appointment of the President, and through his dependence on them, the virtual appointment to offices; among others the offices of the judiciary department. They are to make Treaties; and they are to try all impeachments.” As the plan stood, Wilson asserted “the President will not be the man of the people as he ought to be, but the minion of the Senate.” He went so far as to suggest senators will contrive to ensure all elections fall into their laps.

Roger Sherman (CN), perhaps best known for the Connecticut Compromise that saved the convention in July, said that while he would go along with the existing plan, he proposed an alternative. Why not empower the entire Congress, sitting and voting as states, to immediately vote for a President from the EC’s five top candidates? Presidents would assume office with the backing of the representatives of both the people and states. It was a solution the small state delegates could support.

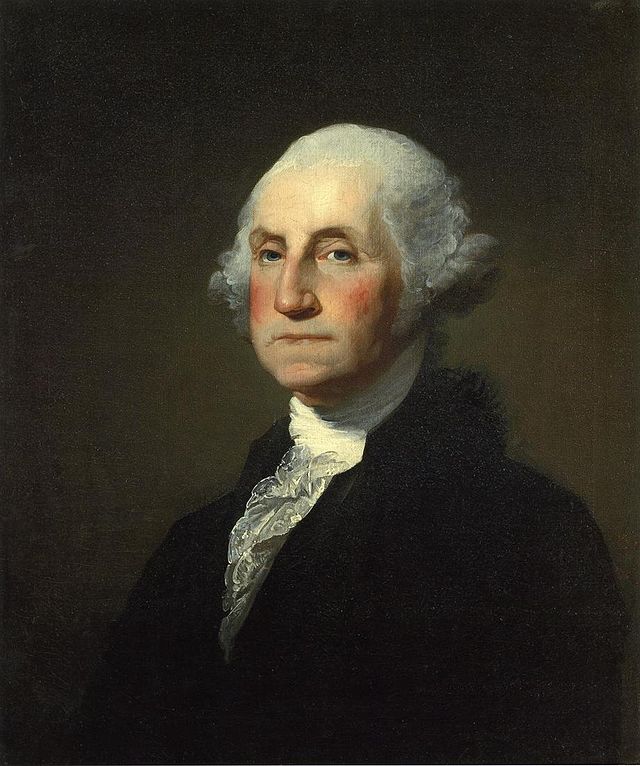

Alexander Hamilton (NY), who said little since his day-long speech in June, supported a previous motion to appoint the majority or plurality winner of the EC. Since the Senate could make the nominee with the fewest number of EC votes the President, he saw no reason for objection.

His proposal went nowhere. The convention moved on to approve by large majorities an unlimited number of four year terms, and the assignment of state electors equal to the number of their legislators in Congress.

Next, delegates passed two seemingly innocuous resolutions we hardly notice today, but were essential to avoid cabal and intrigue. First, the electors would NOT meet in the US capital to cast their votes. This prevented influence and discussion among the electors. Instead, they would cast their votes, in their respective states, on the same day. Second, the recorded votes were sealed and sent to the President of the Senate. In this way, the results of the election weren’t known until the President of the Senate read the ballots aloud to a joint session of Congress. Once again, the convention headed-off backroom deals.

At this moment, so very late in the summer, the fatigued Framers still faced a critical question, “which body of Congress shall elect the President in the event of no majoritarian winner of the EC?” Delegate Hugh Williamson (NC) suggested the entire Congress, voting by state, and not per capita. Sherman immediately cut in to motion the House of Representatives, instead of the Senate or the entire Congress voting by state delegations, one vote per state. It passed 10-1.

George Mason (VA) who ultimately did not sign the Constitution because it leaned too far toward aristocratic government, appreciated Sherman’s amendment as lessening the aristocratic influence of the Senate.

Having established the workings of the EC and the likely election of the President by the House of Representatives voting by state, the Convention completed the essentials of Article II and would formally incorporate it into the Constitution tomorrow September 7th.

Adjourned.

To modern opponents of the Electoral College, the Framers’ system is an archaic holdover from less progressive times. They summarily dismiss it as anti-democratic 18th century nonsense put to paper by the same sort of people who oppress minorities to this day. Part of the misunderstanding of the EC is due to corruption of the system by the two major political parties. It is difficult to read this series and Article II without viewing them through the lens of political party distortions beginning with the choice of electors.

But, for readers with the will to imagine the absence of political party domination and exploitation, the Framers’ system was a beautiful foil to the first enemy of republics: factions. Factions are a republic’s worst enemy, and the soiled system we’ve come to accept, in which the people’s practical choice of electors is limited to one of two outright leaders of factional political parties, makes a mockery of our Framers’ efforts.