How the Supreme Court Rewrote the Constitution

By Rob Natelson – February 21, 2022

The first, second, third, and fourth installments of this series described how the Constitution established a relatively small federal government with limited powers and how President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal challenged that plan. Initially, the Supreme Court tried to balance the New Deal with the Constitution. However, during the years from 1937 to 1944, the court dismantled most of the Constitution’s restraints on federal power. The first two casualties were limits on federal spending (1937) and on federal land ownership (1938).

This installment explores the destruction of constitutional limits on Congress’s economic authority.

Congress’s Economic Powers

The Constitution granted Congress significant, but limited, economic powers. Those powers included passing “uniform Laws on the subject of Bankrupcies,” coining and controlling the currency (pdf), fixing weights and measures, establishing post offices, establishing “post Roads”—that is, intercity highways (pdf)—issuing patents and copyrights, governing federal enclaves and territories, and “regulat[ing] Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian tribes”—the commerce clause (Article I, Section 8, Clause 3).

In addition, the necessary and proper clause (Article I, Section 8, Clause 18) recognized Congress’s prerogative of approving laws “necessary and proper” for carrying out other powers.

Congress’s Commerce Power

The vast expansion in federal economic authority during the years from 1937 to 1944 was made possible by the Supreme Court’s decisions that rewrote the two clauses that, working together, create Congress’s Commerce Power: the commerce clause and the necessary and proper clause. To understand how the court mangled these provisions, we must first understand their original meanings.

When the Constitution gave Congress the authority to “regulate Commerce,” the phrase meant approving laws on the purchase and sale of products and some traditionally associated activities, such as navigation and cargo insurance (pdf). “Commerce” excluded other economic activities, such as production (manufacturing, agriculture, and mining), real estate transactions, and most kinds of insurance. It also excluded non-economic activities, such as crimes of passion, marriage and divorce, religion, and morality. The Constitution left oversight of all of those activities to the states (pdf).

The commerce clause also limited Congress to supervising commerce across political borders. Congress could regulate the sale of shoes by a North Carolina wholesaler to a New York retailer. But only the New York state government could oversee a New York retailer’s sale to a New York buyer.

Those who wrote and adopted the Constitution thoroughly understood that economic and non-economic activities all affect each other. If a wheat grower has a bumper crop, it affects the price of wheat in commerce. Similarly, the price of wheat may influence the grower’s decision to buy more land, marry, or have children. In the 1930s, progressives often claimed that because of interdependence, the federal government should regulate everything or at least all economic activities. They seemed to think that the Founders didn’t understand interdependence or that it was something new (see, for example, the quotation from Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes in the second installment of this series).

But interdependence was nothing new, and the Founders fully understood it. Still, when writing the Constitution, they split responsibility between the states and the central government. They did so because other values (such as freedom) are more important than central coordination.

However, the Founders qualified the split of responsibility with the necessary and proper clause. That clause is too complicated to cover here (curious readers might consult the book “The Origins of The Necessary and Proper Clause”). Suffice to say that it allowed Congress to govern some activities that weren’t exactly “commerce,” but were subordinate (“incidental”) to it. For example, the commerce clause allowed Congress to regulate the shipment of goods across state lines, while the necessary and proper clause permitted Congress to regulate how the goods were labeled for the journey.

1937: Hughes’s Attempted Compromise

The third installment of this series discussed Hughes’s opinion in National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation (pdf). Hughes said Congress could regulate labor relations (part of production, rather than commerce) in a very large interstate company to prevent an “obstruction” to commerce. Hughes’s opinion reveals that he was relying on the necessary and proper clause, although he didn’t use the name.

But for the necessary and proper clause to allow Congress to regulate an activity, it’s not enough that the activity obstructs or otherwise affects commerce. The activity must also be subordinate or “incidental” to commerce—and labor relations are far too important for that. Ultimately, Hughes’s attempted compromise gave more extreme progressives a vehicle for destroying the limits on federal Commerce Power entirely.

1938 to 1941: Progressives Take Over the Court

Retirements after Jones & Laughlin allowed Roosevelt to place New Deal supporters on the bench. The previous installment in this series mentioned Hugo Black (1937) and Stanley Reed (1938). Benjamin Cardozo was replaced by Felix Frankfurter (1938) and Louis Brandeis by the far-left William O. Douglas (1939). The conservative Pierce Butler was replaced by FDR’s attorney general, Frank Murphy (1939). James McReynolds was supplanted by James Byrnes, a pro-New Deal senator (1941).

Also in 1941, Hughes retired. FDR moved the more liberal associate justice Harlan Fiske Stone up to Chief Justice. He then filled Stone’s slot with Robert Jackson, who had succeeded Murphy as attorney general.

By 1942, the court’s make-up stood as follows: nine liberals and zero conservatives.

1941 to 1944: The Court Gives Congress Total Economic Power

In February 1941, the court handed down United States v. Darby (pdf). The Darby Lumber Company was a Georgia enterprise far smaller than the Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation. The issue was whether federal labor law was enforceable against this smaller entity.

Stone’s meandering opinion appears to have relied on the necessary and proper clause, but it never mentioned that clause by name. Stone cited Hughes’s decision in Jones & Laughlin, but ignored the fact that Hughes’s decision was limited to much larger companies.

Stone noted that Congress could regulate any production with a “substantial effect” on commerce, but never defined “substantial effect.” Stone further said Congress may regulate production that’s “so related to the commerce and so [affecting] it as to be within the power of Congress to regulate it,” apparently not recognizing that this statement is circular.

Constitutionally, the portions of Darby just discussed were inane. But they gave a relative handful of federal politicians almost absolute power over every business in the United States.

Roscoe C. Filburn

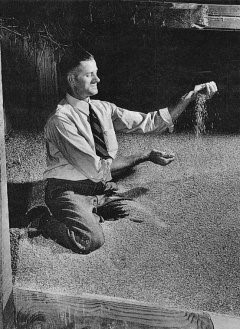

The court’s 1942 case, Wickard v. Filburn (pdf), naturally followed from Darby. Roscoe C. Filburn was a farmer who grew wheat. Pursuant to a New Deal program, the federal government imposed a maximum wheat quota. Filburn didn’t sell more than the quota, but he grew some extra to use on his own farm. The government fined him. The court unanimously upheld the fine.

Jackson’s opinion acknowledged that Filburn’s raising wheat for home consumption wasn’t “commerce.” But Jackson relied on the Darby case and said Congress could regulate Filburn’s decision because his decision, when amalgamated with others like it, had a “substantial effect” on commerce.

Like Hughes before him, Jackson also misrepresented comments by Chief Justice John Marshall.

“At the beginning Chief Justice Marshall described the federal commerce power with a breadth never yet exceeded,” Jackson wrote. “Gibbons v. Ogden … [Marshall] made emphatic the embracing and penetrating nature of this power by warning that effective restraints on its exercise must proceed from political rather than from judicial processes.”

In fact, Marshall never permitted congressional control over production under the pretense that it “affected commerce.” Gibbons v. Ogden (1824) addressed navigation, a subject within the core of the commerce clause. In the same case, he listed activities outside of the scope of federal power, including some that “substantially affect” commerce. He also never said that “effective restraints … must proceed from political rather than judicial processes.” On the contrary, in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) he affirmed explicitly that if Congress exceeded its authority, “it would become the painful duty of this tribunal … to say, that such an act was not the law of the land.”

Jackson’s duplicity in Wickard was exceeded only by Black’s in United States v. South-Eastern Underwriters Association (pdf), decided on June 5, 1944. South-Eastern Underwriters overruled longstanding Supreme Court precedent that held that Congress may regulate all forms of insurance because all of them (not just cargo insurance) are “commerce.”

Black’s opinion for a unanimous court was a classic example of judicial mendacity.

Black claimed that 18th-century “dictionaries, encyclopedias, and other books” defined “commerce” to include all forms of insurance. Yet he failed to cite a single dictionary, encyclopedia, or book saying that (because there are none). He cited a report by Alexander Hamilton, but failed to reveal that Hamilton’s report referred only to cargo insurance. He referenced Marshall’s Gibbons v. Ogden opinion to “prove” that insurance is a form of commerce. Actually, Marshall never mentioned insurance in that case. He also cited a thinly documented 1937 book claiming that “commerce” included all economic activities. But this claim is rebutted by the text of the Constitution itself, which lists other economic activities separately (see above).

When we consider the enormous scope of the current federal regulatory regime, we would do well to remember that the ultimate constitutional justification for most of it consists of the Supreme Court’s mendacious ruling in South-Eastern Underwriters and vague “substantial effects” language from Darby and Wickard.

A flimsy foundation indeed.

Robert G. Natelson, a former constitutional law professor, is senior fellow in constitutional jurisprudence at the Independence Institute in Denver.

Leave A Comment