1861 Washington, DC

In an effort to delay or stop the coming civil war, states called themselves together to meet at the Willard Hotel in Washington DC searching for a way to satisfy both sides of the Nation. The convention process was successful. But the outcome was not.

By Mike Kapic – January 12, 2018

Title:

1861 Washington Conference Convention or the Washington Peace Conference of 1861 or the Old Gentleman’s Conference.

Purpose:

This was an attempt by states, both north and south, to halt the Union’s division and Civil War even as some states were seceding.

Call and Subject:

Several states had promoted the idea of a convention of states for resolving the slave issue as early as 1832. By 1860 conditions worsened enough that the Virginia legislature made the call on January 19,1861, to propose and draft one or more amendments that, if ratified, would weaken extremists in both the North and the South, and thereby save the Union.

Date and Location:

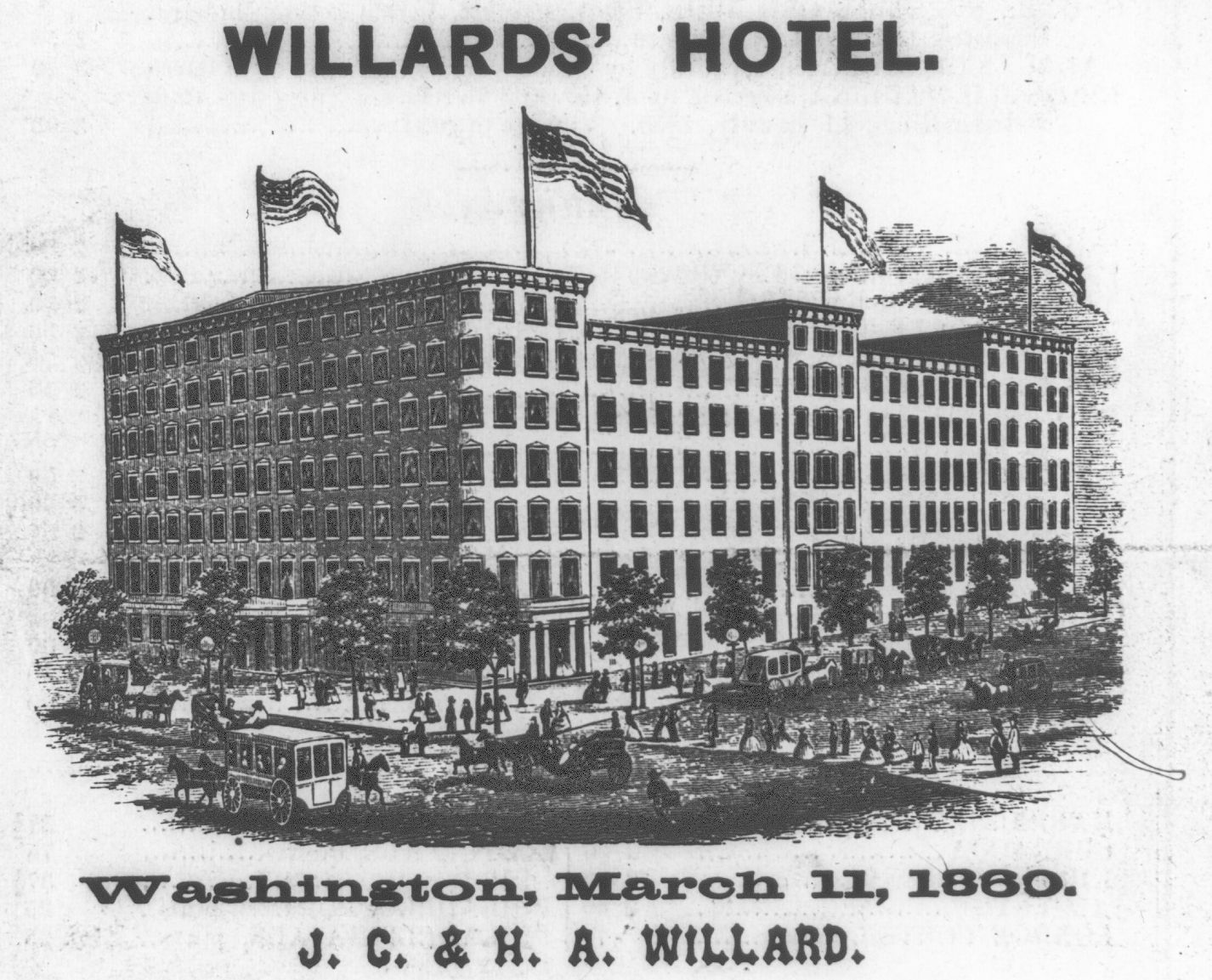

The convention met from February 4 to February 27, 1861 at Willard Hall in Washington DC.

Attendance:

Twenty-one states sent 132 commissioners: NH(3), VT(5), CT(6), RI(5), NJ(9), PA(7), DE(5), MD(7), VA(5), NC(5), KY(6), OH(8), IN(5), IA(4), NY(11), TN(12), IL(5), MA(7), MO(5), ME(8), KS(4).

By the start of the convention, the U.S. was comprised of 34 states and with seven seceding by Feb 4, 1861, 21 of the 27-remaining attended the Washington convention.

Principals:

The commissioners elected (ex-U.S. President) John Tyler (VA), President and Crafts J. Wright (OH), Secretary.

Convention Protocol:

The assembly followed to the letter the convention rules that had been established during the 18th century—the same rules relied on by the Constitution’s Framers when they provided for a “Convention for Proposing Amendments” in Article V of the Constitution.

- This was a national convention.

- This convention adopted the same rules used in the 1787 convention.

- The call for the convention set the place, time, and topic, but did not try to dictate other matters, such as selection of commissioners (delegates) or convention rules.

- At the convention, voting was by state. One vote was, apparently inadvertently, taken per capita, but that was quickly corrected to one vote per state.

- The commissioners from each state were selected in the manner that state’s legislature directed. Most commissioners were elected by the legislature itself. In some states, the legislature delegated the selection to the governor, with or without state senate approval. In a few states, the legislature was not in session, and the governor made the pick.

- The convention adopted its own rules and selected its own officers.

- The convention stayed on topic.

- Private communications on the proceedings could be spoken, but with caution and reserve at the discretion of each member. Nothing spoken during the proceedings was to be published without permission.

Unusual Occurrences:

- This gathering differed from an Article V convention primarily in that it made its call proposal to Congress rather than to the states. The Congress considered sending to the states, but didn’t.

- In most other respects, it was a blueprint for how an Article V convention would conduct itself.

- Seven of the seceding eleven states had already left the Union by Feb 1861 leaving 27 states still in the Union. Eventually eleven states would leave the Union to join the Confederacy.

- Several commissioners made motions that were arguably off topic (changing the President’s term of office and others), but they were voted down without debate and threatened with expulsion. [An unabated introduction of a new topic like this is what some refer today as the technique for guaranteeing a runaway convention. History has proven that they don’t succeed.]

- A commissioner from Ohio passed away during the convention.

Conclusions:

The convention produced a seven-point amendment that compromised and weakened both sides in their attempt to stop the Civil War, but Congress failed to act and send it to the states for ratification. However, the convention operated like previous conventions.

The amendment proposed would have protected slavery where it existed, but by confining it territorially probably would have doomed it to eventual extinction.

Scholar and historian Rob Natelson commented, “This convention’s efforts eventually failed, but the failure was that of Congress, not of the convention. The convention did its job—proposing a workable compromise—but Congress failed to propose it formally for ratification. And while some states had applied for an Article V convention, their applications were too few, too late.”

[Ed: This is an excerpt chapter from Conventions That Made America: A Brief History of Consensus Building, by Michael Kapic, 2018, chapter 32]