Privatizing Airport Security Would Make Americans Safer and Richer

Overall, this reform has the potential to save taxpayers money, increase their travel safety, and decrease their headaches at the airport.

David Inserra January 25, 2019

The flu season isn’t the only thing keeping some Transportation Security Administration agents out of work. As the partial government shutdown rolls on, TSA paychecks aren’t coming in, and more agents are calling in “sick” as a result.

On Monday, the TSA reported a nationwide absence rate of 6.8 percent. That’s far higher than the absence rate of 2.5 percent, which was reported on the same day one year ago.

Noticeably, some airports are doing fine and still paying airport screeners despite the government shutdown. San Francisco International Airport, for example, is able to operate as normal because it is one of 22 airports in the U.S. that use private airport security, not TSA agents.

The Perks of Privatization

There are multiple reasons why reforming the TSA model would prove beneficial. A private model would allow for strengthened accountability, a decrease in operation costs, enhanced management of labor, and better focus on security threats and problems.

Privatizing aviation screenings would be beneficial for security. Private screening services can provide security that is at least as good as federal services, and at a cheaper rate. This is accomplished through the creation of incentive, competition, and accountability.

The core issue with the TSA model is the present conflict of interest created by self-regulation. Currently, the TSA is operating as both the security regulator and security provider.

As Reason Foundation transportation expert Robert W. Poole Jr. testified to Congress:

[The] TSA regulates itself. Arm’s-length regulation is a basic good-government principle; self-regulation is inherently problematic. First, no matter how dedicated TSA leaders and managers are, the natural tendency of any large organization is to defend itself against outside criticism and to make its image as positive as possible. And that raises questions about whether TSA is as rigorous about dealing with performance problems with its own workforce as it is with those that it regulates at arm’s length, such as airlines and airports.

Better Models

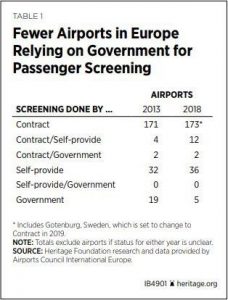

The TSA model is quite uncommon worldwide. The more common models utilize the government as a security regulator while a contractor or the airport itself provides security. This automatically pushes accountability and competition higher than the current U.S. model.

Here’s one example of how a private model would improve accountability.

In recent years, the TSA has struggled to carry out its duties. That was made painfully clear by the results of the “red team” auditing test, where 67 of 70 weapons passed through TSA screeners.

If the red team test had been performed on a private contractor and yielded similar results, they would likely have been immediately fired and replaced by one of their competitors. But the TSA is not so easily replaced.

By looking to examples in Canada and Europe, we can observe how governments spend drastically less yet still manage to meet international aviation standards. These countries show that privately-hired scanning teams can manage personnel far more efficiently than the government and still make a profit. They also cost significantly less—Canada spent about 40 percent less per capita on aviation security than the U.S. in 2014, for example.

Shifting the responsibility for front-line aviation screening into the private sector would also improve security by letting the TSA focus purely on oversight and regulation.

The way forward for aviation security is through privatization. An easy way forward would be for policymakers to look to the Canadian model for private aviation security as one that the U.S. could easily learn from and adapt to meet U.S. needs.

Overall, this reform has the potential to save taxpayers money, increase their travel safety, and decrease their headaches at the airport.

David Inserra is a policy analyst for The Heritage Foundation’s Allison Center for Foreign Policy Studies, specializing in cyber and homeland security policy, including protection of critical infrastructure.