Shaping the Electoral College, Part VIII

By Rodney Dodsworth, August 29, 2019

July 24th, 1787. More blind alleys.

Let the schizophrenia continue! A couple days ago, delegates passed the framework of what we’d recognize as the Electoral College. State legislatures appointed electors. The only remaining substantial question was “how many votes per state?” Well, that progress vanished today. To get an idea, here are my Cliff Notes to the day’s proceedings:

- Divide the nation into three electoral districts to select three executives.

• Fear an elected Monarch.

• Electors equal in number to the State’s Congressional delegation was resoundingly defeated.

• Return to Congressional appointment by 7-4 vote.

• Executive must be independent of Congress after the election. A single twenty year term?

• To prevent intrigue, draw fifteen Congressmen by lot to immediately vote and elect an Executive.

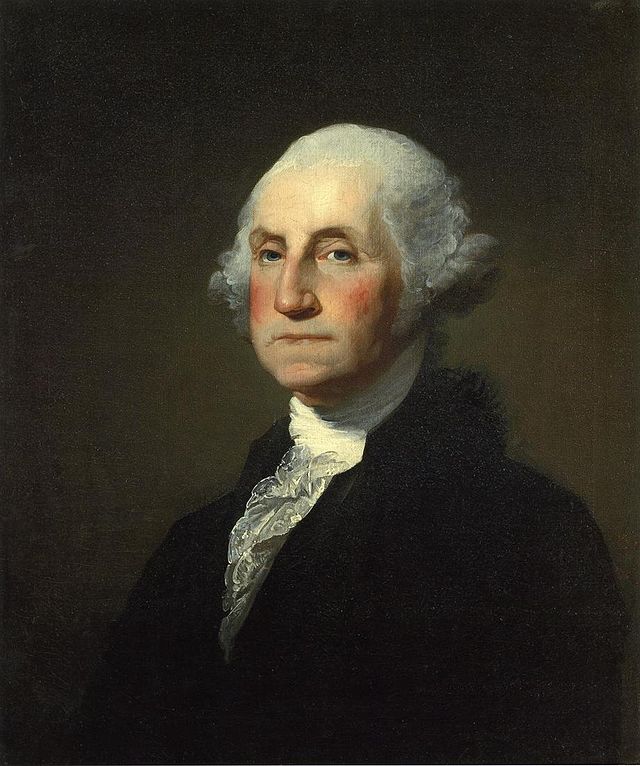

It is worthwhile, while we are down here in the weeds, not to forget that the central purpose of the Framers’ electoral system was to provide an endless succession of men like George Washington, men of unsurpassed public virtue and executive ability. To this end, we haven’t seen recent motions to popularly elect the chief Executive . While the people of the time would certainly have elected Washington, there was no telling what sort of demagogues a duped people would fall for in the future. The American President wasn’t to be the tool of any faction, political party, state governors, or branch of government. As Gouverneur Morris warned today, “Original vice here could not be corrected.” The Framers had to get it right. They did.

In Convention, the appointment of Executive Electors resumed.

Gouverneur Morris (PA) – Of all possible modes of appointment, that by Congress is the worst. If the Congress is to appoint, and to impeach or to influence the impeachment, the Executive will be the mere creature of it. Only a few days earlier, Morris was opposed to impeachment but was now convinced the Constitution must provide for impeachment if the appointment was to be of any extended duration. No man would say that an Executive known to be in the pay of a foreign power should not be removeable in some way or another.

Some delegates found Morris inconsistent regarding his trust in legislatures. He explained that legislatures are worthy of unbounded confidence in some respects, and liable to equal distrust in others. When their interest coincides precisely with that of their constituents, as happens in many of their Acts, no abuse of trust is to be apprehended.

But when a strong personal interest opposes the general interest, no legislature is trustworthy. In all public bodies there are two parties. The Executive will necessarily be more connected with one than with the other. There will be a personal interest therefore in one of the parties to oppose as well as in the other to support him. Much had been said of the intrigues that will be practiced by the Executive to get into office. Nothing had been said on the other side of the intrigues to get him out of office. Some party leader will always covet his seat, will perplex his administration, will cabal with the Legislature, till he succeeds in ousting him.

If the delegates to this Convention did not provide a good organization of the Executive, he doubted whether we should not have something worse than a limited Monarchy. To avoid dependence of the Executive on the Legislature, the expedient of making him ineligible to a second term had been devised. This was as much as to say we should give him the benefit of experience, and then deprive ourselves of the use of it.

But make him ineligible a second time and extend his term to say, fifteen years; will all the men to this office reliably step down? No. If just one is unwilling to quit “the road to his object through the Constitution,” he will have the sword, a civil war will ensue, and the Commander of the victorious army on whichever side, will be the despot of America.

This consideration renders him particularly anxious that the Executive should be properly constituted. The vice here would not, as in some other parts of the system, be curable. It is the most difficult of all rightly to balance the Executive. Make him too weak, and Congress will usurp his powers: Make him too strong, and he will usurp Congress. He preferred short terms and re-eligibility, but a different mode of election.

Furthermore, and with an eye on ratification, the Constitution was doomed if the people sniffed out an infant Monarch. Morris would vote against any such plan of extended Presidential terms.

And as for James Wilson’s suggestion – draw fifteen Congressmen by lot to immediately vote and elect an Executive, Morris found this method safer than the intrigue and corruption certain to accompany Congressional elections.

Adjourned.