Shaping the Electoral College, Part VI

by Rodney Dodsworth, August 22, 2019

July 17th and 19th, 1787.

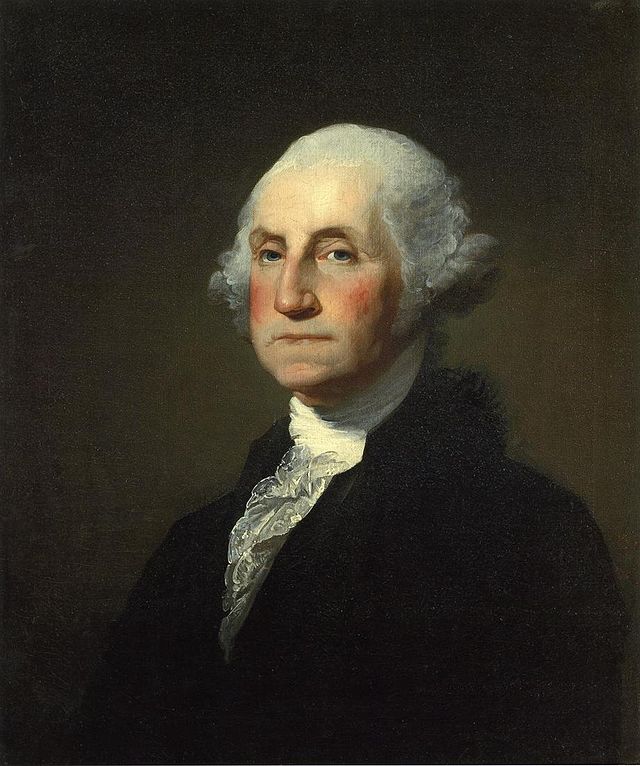

No other topic at the Federal Convention, our Article II chief Executive, demanded more time and debate. Our Framers needed some sixty votes to arrive at their brilliant Electoral College. Unlike the politics of redesigning Congress, the chief Executive emerged not from the clash of wills between large and small States, but from a series of ingenious efforts to design a new institution suitably energetic but safely republican. From the beginning to the end of the convention, delegates wrestled with Executive powers, the balance of those powers with Congress, and how a free people could design an office that prevented the trappings of monarchy, minimized internal and external corruption, promoted men like George Washington.

Having survived the day before a near breakup and dissolution over equality of State representation in the Senate, delegates returned to the Executive branch, this time meeting in Convention.1 It was time to thrash through the recommendations of the committee-of-the-whole, and we’ll see over the next few days a schizophrenic quality to the proceedings.

Delegates bounced back and forth between weak chief Executives dominated by Congress and strong Executives independent of Congress. Ditto for term length and re-eligibility for office. A weak Executive, a simple administrator of the law, could be trusted for much longer terms, perhaps even for life on condition of good behavior, than a strong Executive with a veto power over congressional bills, military duties, and influence over judicial appointments and treaties.

- If the Executive was appointed by Congress, expect a creature of Congress.

• Popular nationwide election by freeholders? Only one vote in favor.

• House appointment retained by 9-1 vote.

• State legislatures to appoint electors was defeated 8-2.

• Unanimous vote for Congressional appointment.

• Unlimited number of terms passed 6-4.

• One election, Executive-for-life conditioned on good behavior was defeated 6-4.

Notice that four States voted for an Executive-for-life, and only two voted in favor of State-appointed electors. Such was the discomfort and disorientation.

19 July 1787.

As delegates continued to chase their tails on July 19th, we’ll see that Alexander Hamilton doesn’t deserve the modern opprobrium as the sole “monarchist” at the convention. No matter one’s views today, delegates in 1787 respected the English monarchy as an institution. English kings were above faction. They were not political party leaders and as such put the welfare of their kingdom ahead of narrow interests. Being hereditary, they were motivated to bequeath a peaceful, prosperous, and happy kingdom to their heirs. What would motivate American Presidents with short terms to leave behind a happy republic?

This is why delegates had difficulty deciding between short v. long, and single v. multiple terms of office. A man limited to a single, short term, could hardly be expected to work in the long-term interests of the nation if the next guy could as easily undo his work. In time, the office could easily become one of personal enrichment. On the other hand, if he was popularly re-electable, the people would regularly judge his performance and thus join his interests with those of the nation. Or would they? Are the people trustworthy?

But . . . if Congress appointed him, multiple-term Executives would coddle Congressional favor by rubber-stamping legislation and offering lucrative Executive branch jobs to Congressmen’s family and friends. The national interest of this President couldn’t possibly figure high on his list of priorities. This institution invited factional chief Executives.

The Convention toyed briefly with a President for life conditioned on good behavior. A weak Executive over a nation stretching perhaps from sea to sea and with dozens more States just wouldn’t do. No matter the mode of election, either popular or by Congress, a lifelong chief Executive could focus, like the ideal monarch, on the good of the American republic without answering to political debts in his continual efforts to secure reelection.

Gouverneur Morris shared his thoughts as to what he expected of a proper “Executive Magistrate.” It is necessary that he should be the guardian of the people against legislative tyranny, against the great and the wealthy who in the course of things will occupy Congress. Wealth tends to corrupt the mind and nourish its love of power, and stimulates it to oppression. History, he said, “proves this to be the spirit of the opulent.”

The check provided by the Senate over the House was not meant as a check on legislative usurpations of power, but on the abuse of lawful powers, on the propensity in the House to legislate too much to run into projects of paper money & similar expedients.2 A Senate of the States isn’t a check on legislative tyranny. On the contrary it may favor tyranny, and if the House can be seduced, it may find the means of success. The Executive therefore ought to be so constituted as to be the great protector of the people.

Morris also disfavored impeachment and removal of a Congressionally appointed life-long Executive Magistrate because it will constitute a threatening sword over the Executive’s head during the inevitable policy disputes. Morris: “It will hold him in such dependence that he will be no check on the legislature, will not be a firm guardian of the people and of the public interest. He will be the tool of a faction, of some leading demagogue in the legislature.”

Morris saw no alternative for making the Executive independent of the legislature but either to give him his office for life by the legislature, or make him re-electable every two years by the people themselves.

Since a President for life smacked of monarchy, and the people weren’t trusted in direct elections, the Convention, slowly, by degrees, was reasoning itself toward an electoral form that avoided dependence on Congress as well as an uninformed public.

Some sort of intermediate electors independent of the people and Congress would do the trick.

Shall the Executive be appointed by electors? Yes, 6-3.

Shall electors be chosen by State Legislatures? Yes, 8-3.

Limit the Executive to one term? No, 8-2.

Seven year terms rejected. Six year terms passed 9-1

Adjourned.

- Connecticut Compromise – Equal State representation passed by a bare 5-4-1 on July 16th. A very close call. Delaware’s Paterson was so angry during the debate he offered to second any motion for the convention to adjourn sine die. Rakove, J. N. (1996). Original Meanings – Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution. New York : Random House. 80.

2. Delegates knew very well of Gouverneur Morris’ reference to John Locke, who described usurpation as the exercise of power entitled to another. Tyranny is the exercise of power beyond right, to which nobody may access. For instance, Executive or Judicial branch lawmaking, if related to Article I Section 8, is a usurpation of Congressional authority. Laws established by any branch outside Constitutional limits is tyranny.