New Hampshire Is Fighting Back to Defend the Electoral College

Tara Ross – January 14, 2020

The New Hampshire Legislature is considering a bill that would block the release of popular vote totals until after the Electoral College has met.

New Hampshire legislators have introduced an election bill that would be completely unacceptable under normal circumstances. But these are not normal times.

Constitutional institutions, especially the Electoral College, are under attack.

Extraordinary action may be needed. Thus, some New Hampshire legislators have proposed to withhold popular vote totals at the conclusion of a presidential election. The numbers would eventually be released, but not until after the meetings of the Electoral College.

The idea sounds crazy and anti-democratic. In reality, however, such proposals could save our republic: They will complicate efforts to implement the National Popular Vote legislation that has been working its way through state legislatures.

National Popular Vote’s plan has been gaining steam in recent years. The California-based group asks states to sign an interstate compact—basically, a simple contract among states. Signatory states agree to award their electors to the winner of the national popular vote, regardless of the outcome within their own state borders.

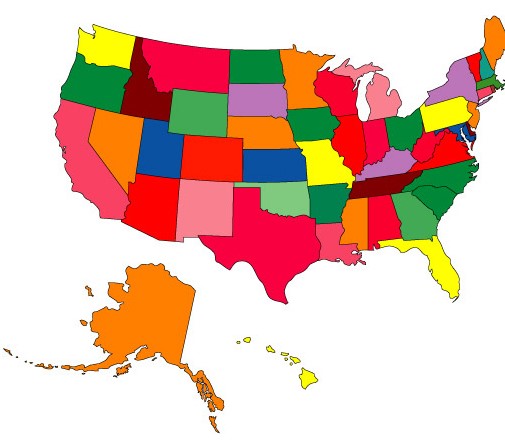

The compact goes into effect when states holding 270 electors—enough to win an election—have agreed to participate. So far, 15 states plus Washington, D.C., have signed. They have 196 electoral votes among them. Seventy-four more electors are needed.

National Popular Vote is pushing hard to get those last few votes. Its legislation has already been introduced in states such as Virginia (13 electors) and Missouri (10 electors). Meanwhile, lobbyists have been paving a path for success in other states such as Florida (29 electors).

In other words, National Popular Vote is on track to effectively eliminate the Electoral College, even though it’s supported by only a minority of states.

Fortunately, other states don’t have to calmly submit. They can protect themselves, and that’s where New Hampshire’s proposal comes in. It could confuse National Popular Vote’s ability to generate a national popular vote total. Without that tally, National Popular Vote’s compact fails.

Remember, the federal government doesn’t generate an official national tally because U.S. presidential elections are conducted state by state. Thus, National Popular Vote’s compact requires its member states to generate their own assessments of the national popular vote. They are to look to state reports and “treat as conclusive an official statement” from any state regarding the popular vote in that state.

That requirement creates many opportunities for those states that have not agreed to the National Popular Vote compact.

What if a state such as New Hampshire simply refused to release its popular vote totals, as has been proposed? Or what if states were to release totals for winning candidates, but didn’t report any total for the losing candidates?

National Popular Vote proponents will claim that such proposals violate federal reporting requirements, but they don’t. Those federal laws cannot require a state to turn in popular vote totals.

After all, the state wasn’t constitutionally required to hold a popular vote in the first place. The state legislature could have appointed electors directly instead, as sometimes occurred in our country’s early years.

Moreover, the federal law is vague, calling for states to report “the canvass or other ascertainment.” The deadline for such information is “as soon as practicable.”

“As soon as practicable” doesn’t occur until after the meetings of the Electoral College when constitutional institutions are under attack.

Other ideas would work just as well as the proposal in New Hampshire.

What if a state were to change its election system altogether? In Texas, for example, voters currently cast one ballot for an entire slate of 38 presidential electors.

What if each potential elector were listed on the ballot instead?

Every Texan would be given 38 votes and asked to vote for 38 individual electors. Texans could vote for Republican electors, Democratic electors, independent electors—or even some of each. The 38 individuals with the highest vote totals would represent Texas in the Electoral College.

That system was used in Alabama in 1960. Alabama voters were fairly represented by electors of their own choosing, but political scientists to this day still can’t agree on how to compute the “Nixon versus Kennedy” tally.

Interestingly, each elector received a different number of votes, indicating that many Alabamians did not vote a straight ticket.

How would National Popular Vote states pinpoint a national tally with so much information missing?

They couldn’t. Any “national popular vote total” generated would be an invention of the imagination. Such a situation surely would give the Supreme Court even more cause to strike down National Popular Vote’s efforts to effectively eliminate the Electoral College without the constitutionally required approval from a supermajority of states.

James Madison once wrote that state governments should respond to “ambitious encroachments of the federal government” with “plans of resistance.”

National Popular Vote is not an “ambitious encroachment of the federal government,” of course. It is a group of states colluding to bypass constitutional requirements.

But Madison would surely find “plans of resistance” appropriate in this context, too.

Tara Ross is a retired lawyer and author of several books, including “The Indispensable Electoral College: How the Founders’ Plan Saves Our Country from Mob Rule,” and “We Elect a President: The Story of Our Electoral College.”

Additional reading:

Electoral College Opponents Attempt to Have It Both Ways

Ditch the Electoral College, and Small States Will Suffer

Liberals Claim Electoral College Is Biased. Here Are the Facts.

Correcting Media Distortions About the Electoral College

The Intellectual Dishonesty of the Campaign Against the Electoral College