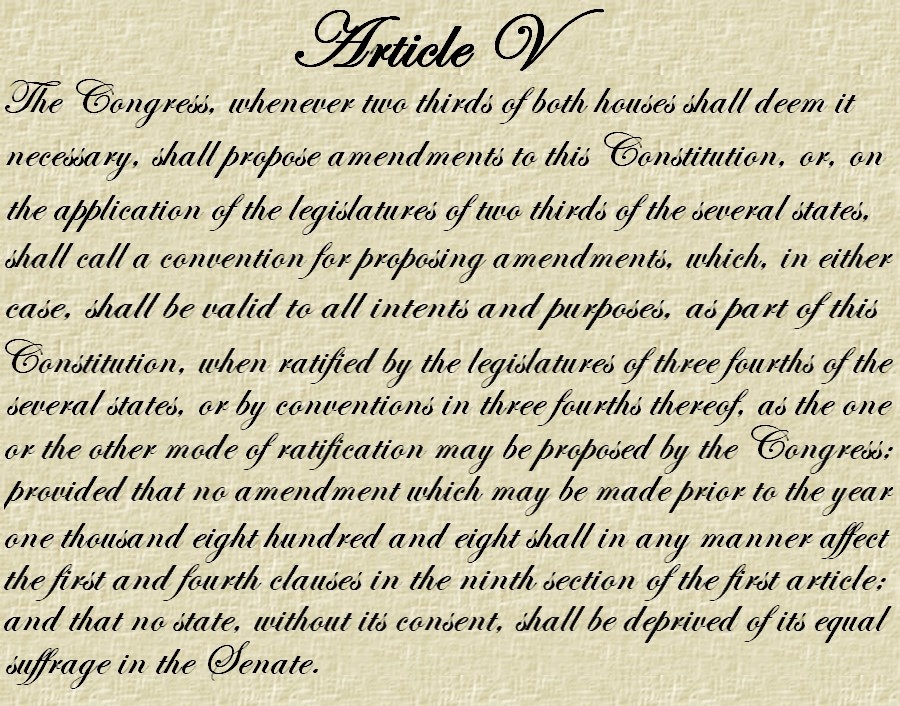

The U.S. Constitution’s Article V.

By Mike Kapic – January 26, 2026

Summary

The Founders knew their attempt at reforming the Articles of Confederation, the newly renamed Constitution, was not perfect. Therefore they included a way, the second clause in Article V for the people through their states, to continue the process of reform and repair toward a more perfect union.

“[Article V] equally enables the general and the state governments to originate the amendment of errors, as they may be pointed out by the experience on one side, or on the other.” – James Madison, Federalist 43

***

1814 Hartford convention attempt to end the War of 1812

The Framers purpose for the Constitution’s Article V was to give the people and their states a way to amend the national government when it became necessary. The states Framers used the 170-year-old convention process to reform their failing government and strongly believed it would be used again. They codified the process equally with Congress and the States to propose changes. They required the States to ratify proposals by either legislatures or the people in conventions.

According to Madison, Charles Pickney introduced a way to propose changes to the reformed Article of Confederation on May 29, 1787 as Article XVI. Over the coming months it morphed into Article V. The final wording was famously revised two days before the final vote on September 17, 1787, by George Mason.

Amendments have been used since the First Congress to reflect the changing desires of the general populace.

Article VII of the U.S. Constitution required that, in 1787, the people in state’s conventions would approve or decline their new proposed form of government, the U.S. Constitution. Nine states would be required, but all thirteen did approve.

The most frequent complaint from the people in the ratification conventions was the lack of a bill of rights, similar to Virginia’s. Madison fulfilled his promise of a Bill of Rights by introducing twenty amendments in the First Congress of which it approved 12 and the states quickly ratified ten: the Bill of Rights.

The eleventh was approved in 1992 as the 27th Amendment with the help of University of Texas student Greg Watson’s report when, after graduation, he lobbied the remaining states necessary to approve it some 200 years after it was introduced. His professor at the time gave his report a ‘C’, noting it couldn’t be done. The university subsequently revised the grade to an ‘A’.

It doesn’t take many: E Puribus Unum, ‘from many, one.’

Amendments have been added validating the Framers contention that the Constitution “wasn’t perfect and it was up to the people to adjust it as required through proposed amendments,” toward a more perfect union.

Example:

- 19th Amendment nationalized the vote for women.

- 14th redefined the states’ rights under the Constitution among other changes.

- 26th the right to vote reduced to 18 years of age.

- 24th banned poll taxes.

- 18th banned making alcohol.

- 21st repealed the 18th.

- Five of twelve 20th century amendments have in some way expanded voting rights.

Congress has attempted to propose amendments to the Constitution over 12,000 times and succeeded 33 times with only twenty-seven being ratified by the states. It’s is a difficult process that has accomplished meeting the people’s wishes.

The people have agreed to amending their state’s constitutions thousands of times due to their simpler process and with fewer approval restrictions in their states. All fifty-one constitutions reflect, through the amendment process, the wishes of their populace.

Some fear that allowing the states to propose amendments would be dangerous for America. But, for some reason, they don’t fear Congress (with 12% approval) proposing amendments while the states (60% approval) have given their people constitutional limits on state financial accountability. Something the Congress does not have and the reason for a balanced budget or fiscal responsibility amendment proposal by the States today.

Claims of fear that states in convention proposing an amendment is any different or more dangerous than Congress proposing an amendment is constitutional mysticism. The fear is unfounded.

The mechanics of both submitting bodies, Congress or States, propose amendments in exactly the same manner, using similar resources, committees, language style, voting, bias’s, motive’s, rules, and record keeping. The Constitution is not changed by either Congress or the States in the proposal phase. It changes only after the ratification by the threshold state.

But most of America is unaware of the recoded history, here, here and here, of the hundreds of conventions including the one that invented our Constitution in 1787.

Some of Congress’s Constitutional proposed applications and missteps are revealing. Congress has attempted to propose amendments to:

- Ban Drunkenness

- Ban Divorce

- Abolish the office of the presidency

- Choose the next president through a bingo cage.

- Rename the USA, the U.S. of the World

- Only allow women spinsters and widows the right to vote.

- Change We the People’s authority to God’s authority.

- Prevent Chinese-American citizens the right to vote.

- Ability to remove citizenship from African-Americans.

- Require a national referendum vote on whether or not to declare a war.

- Protect all migration birds.

Calling an authorized Article V amending convention of states as a ‘con con’, aka constitutional convention, disrespects We the People and all who’ve served it, some paying the ultimate price. Amending and constitutional conventions are two distinct entities designed to achieve different purposes. The U.S. has had two constitutional conventions in its history, 1787 Philadelphia and 1861 Montgomery. And over 650 recorded colony/state conventions since the early 1600s have been found, including the 1787 Constitutional convention.

The states have submitted over 600 applications to Congress to meet and propose changes since 1788. None have been approved. Frustrated by Congress for ignoring their rightful demands, the states have met in four non-Article V conventions that produced amendments to the Constitution that were never ratified: 1814 Hartford (end a war), 1850 Nashville (Southern solidarity), 1861 Washington DC (prevent Civil War), and 1889 St. Louis (expose anti-trust monopolies). The States know how to operate an amending proposal convention.

Phoenix BBA Planning Convention-2017

The next convention will operate just like the 2017 Phoenix BBA Planning convention did following the established standard operating procedures including those of the 1787 Philadelphia convention.

Examples of a few of the 600 plus subject applications by state submissions to Congress to hold an Article V convention:

- Direct election of Senators

- Direct election of President

- Plenary (the authority to join any other state application)

- Anti-polygamy

- Revision of Article V

- Repeal Eighteenth Amendment

- Taxation of securities

- Minimum wage

- Repeal of the Sixteenth Amendment

- Coercive use of federal funds

- Federal taxing power

- Selection and tenure of federal judges

- Balanced budget amendment

- Apportionment

Congress has intentionally and by design, ignored the states.

The people’s authority and rights for their States to apply for a Constitutional amendment process has been denied by Congress far too long. Failure to support a supermajority of 39 of 34 required applications in 1979 and 36 in 2016 of what the people want in their governance undermines the principle of self-governance. It revels the irresponsibility of their employees to provide it.

Here are examples of Congress’ attempt to preempt the States rights. Archive and FFSF.

The Congressional Judiciary agrees that Congress has no discretion in deciding the call. The States control the entire process after the announcement or call that the States have met the threshold.

The current effort is to propose and present a balanced budget fiscal responsibility amendment(s) to the people by our states. This is to preempt the threat of bankruptcy and/or collapse of our Nation by Congress in its pursuit of more debt.

Next, Part III, How does a convention work?

Leave A Comment