Wickard v. Filburn: The Supreme Court Case That Gave the Federal Government Nearly Unlimited Power

The Constitution creates a government of enumerated powers, which means the federal government is only authorized to do things that are specifically listed in the Constitution.

By Antony Davies & James R. Harrigan – February 7, 2020

Every presidential election in the United States follows a clear formula. First, many people with absolutely no chance of winning the presidency declare their candidacies. Those who get washed out of the race late in the game see their fortunes rise, which was their goal from the first. Second, candidates with even a chance at winning their party’s nomination drift to the outer fringe of their party’s ideology. For Democrats this year, that means appealing to the most progressive of the progressive wing of their party. Finally, when the race is set with two candidates, each of them will converge in the middle, eschewing the ideological members of their own parties.

This is so common that every politically observant American is fully aware of what is happening. But this dyed-in-the-wool process obscures the most pernicious element of every presidential campaign, which sees both the candidates and the voters they hope to attract ignoring the Constitution at every turn. To the shame of both groups, they don’t even seem to realize what they’re doing.

Presidential candidates lay out their respective agendas, from Bernie Sanders’s plan to move to single-payer health care to Donald Trump’s plan for a wall on our southern border to Elizabeth Warren’s plans for just about everything else. But nearly all of these plans are unconstitutional twice over: not only are presidents not given the authority to do these things, but the federal government itself is also not empowered to do these things.

Enumerated Powers

The Constitution creates a government of enumerated powers, which means the federal government is only authorized to do things that are specifically listed in the Constitution. And that list is relatively short. The list appears in Article One, Section Eight and enumerates the proper objects of congressional legislation. Congress can:

- borrow money, coin money, regulate its value, and punish counterfeiters

- regulate commerce with foreign nations, among the states, and with Indian tribes

- establish rules for naturalization and bankruptcy

- establish Post Offices and Post Roads

- issue patents and copyrights

- establish courts inferior to the Supreme Court

- punish pirates

- suppress insurrections, repel invasions, declare war, raise an army, maintain a navy, and make rules for the army and navy

- organize the Militia (leaving to the states the appointment of officers and the authority of training the Militias)

That’s it. This is all the Constitution permits the federal government to do.

Consider the United States’ ill-advised flirtation with Prohibition—which was enacted almost exactly 100 years ago. Nowhere in the Article One, Section Eight powers does one see the authority to “ban the manufacture, transport, or sales of alcohol within the United States.” When Americans decided that they wanted a coast-to-coast ban on alcohol, they amended the Constitution to give the federal government this authority. Fourteen dry years later, Americans came to their senses and revoked this authority by amending the Constitution again. The 21st Amendment was the only amendment ever ratified for the purpose of undoing a previous amendment. But notice the difficulties that honest people faced when trying to accomplish a pervasive political goal.

Constitutionally Limited Federal Government

As of 1933, when the 21st Amendment was ratified, Americans still had a constitutionally limited federal government and what Justice Louis Brandeis famously called “laboratories of democracy” in the states. The purpose of limiting the federal government’s authority so severely was to put the lion’s share of governance in state hands. Each state would govern somewhat differently and, in so doing, the nation would be a huge experiment in democracy.

States that governed well would gain businesses and population. States that governed poorly would lose. By observing what other states did well, each state could learn how to govern better. By losing businesses and population, each state would have an incentive to act on what it learned. The “laboratories of democracy” brought to Americans’ political lives what market competition brought to their economic lives.

But who ended up being tasked with deciding what Article One, Section Eight actually meant? Herein lies the wrinkle that enables all manner of constitutional mischief in the United States. The institution that ended up deciding what the federal government is empowered to do is itself a branch of the federal government. And it should come as no surprise that when push comes to shove, the Supreme Court routinely finds in favor of empowering the federal government.

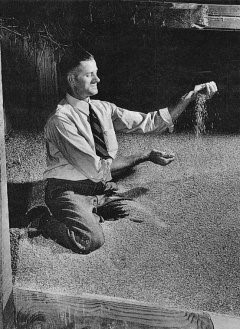

This sort of mischief flowered fully in the decade following ratification of the 21st Amendment. In 1942, the Supreme Court decided a case, Wickard v. Filburn, in which farmer Roscoe Filburn ran afoul of a federal law that limited how much wheat he was allowed to grow.

Regulating the Wheat Market

A careful reader might, and should, ask where the federal government’s right to legislate the wheat market is to be found—because the word “wheat” is nowhere to be found in the Constitution. Be that as it may, the federal government’s aim was clear enough. It was to keep the price of wheat high enough for farmers to remain profitable. The Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938 put an upper limit on how much wheat farmers were allowed to grow, which would serve to keep prices high by limiting supply.

Roscoe Filburn had grown 12 more acres of wheat than the law allowed. But not only did he not sell the excess wheat outside of his home state, but he also didn’t sell it at all. He used the wheat from those 12 acres to feed his cattle.

Filburn was very clearly not engaging in commerce, let alone interstate commerce, yet the Supreme Court found (unanimously) that because Congress had the authority to regulate interstate commerce, Congress also had the authority to prohibit Filburn from growing those 12 acres of wheat for his own use. The Supreme Court’s “reasoning”?

Had Filburn not fed his cattle that excess wheat, he would have been forced to purchase wheat on the open market. And even if he purchased wheat that was grown within his home state, doing so would have made less wheat available within his home state for other wheat buyers. Consequently, some wheat buyers within his home state would then have had to buy wheat from outside the state. Therefore, Filburn’s non-commercial activity was, according to the Supreme Court, interstate commerce.

Interstate Commerce

The mental gymnastics that went into this ruling made just about any activity interstate commerce by definition. Since Wickard, any time Congress has wanted to exercise power not authorized by the Constitution, lawmakers have simply had to make an argument that links whatever they want to accomplish to interstate commerce. Why? Because they know they can get away with it.

So today we have NASA, the FDA, the USDA, the EPA, federally subsidized student loans, Medicare, Medicaid, a federal minimum wage, and hundreds of other federal agencies, programs, and initiatives. Some of these do, indeed, involve interstate commerce. Many do not. A century ago, we amended the Constitution when we wanted the federal government to exercise a new authority—that of banning alcohol.

Today, we allow Congress to exercise almost any authority it likes. Further, we allow Congress to hand its authority over to unelected bureaucrats. So, whereas regulating alcohol required amending the Constitution, regulating marijuana requires only legislation. Regulating prescription medicines requires only bureaucratic action.

We have progressed so far down the path of reinterpreting the Constitution as a document that empowers government, rather than one that limits it, that unelected bureaucrats today exercise power that the Constitution even withholds from Congress. This is troubling even when those bureaucrats are benevolent, altruistic, informed, and intelligent. But when they aren’t, it is extremely dangerous.

And as if all that weren’t bad enough, we now have presidential candidates detailing their agendas to the voting public. If Congress, enabled by the Supreme Court, has overstepped its constitutional bounds, the presidency has eclipsed the very definition of the office. The president heads the executive branch of government. Its role, by definition, is to execute the laws that Congress passes. But presidential candidates present themselves in legislative terms. They do this almost every time they offer a “plan” for anything.

Nearly Limitless Government Power

Congress is charged with the legislative function, and this they are intended to exercise within a constitutional framework deliberately designed to make that job exceedingly difficult. Why were things designed this way? To limit the ability of the federal government to do much of anything without extremely broad support. This is what safeguards the rights of the individual.

When Roscoe Filburn’s right to grow wheat on his own land to feed his own cattle was violated, the rest of this was largely a foregone conclusion.

The sad result has been a government nearly limitless in its power. Sadder still is what this has done to our elections: Every four years, the American people ask candidates for more things neither the president nor Congress is constitutionally authorized to deliver. And this encourages a brand of candidate to run for office who is willing to ignore the Constitution in exchange for winning elections.

The first step to stopping this process lies in reading, understanding, and applying the Constitution of the United States. This means, first and foremost, placing the legislative function in the hands of Congress alone and taking seriously Article One, Section Eight.

It means, in short, limiting government again.

Dr. Antony Davies is the Milton Friedman Distinguished Fellow at FEE, associate professor of economics at Duquesne University, and co-host of the podcast, Words & Numbers.

James R. Harrigan is Managing Director of the Center for Philosophy of Freedom at the University of Arizona, and the F.A. Hayek Distinguished Fellow at the Foundation for Economic Education. He is also co-host of the Words & Numbers podcast.