Sons of Liberty — The Fight for Freedom

“The tree of Liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.” Thomas Jefferson

“Our cause is noble; it is the cause of mankind!” —George Washington

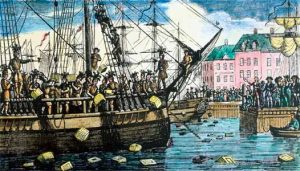

On December 16th, 1773, “radicals” in Boston, members of a secret organization of American Patriots called Sons of Liberty, boarded three East India Company ships at Griffn’s Wharf and threw 342 chests of British East India Company tea into Boston Harbor. This iconic event, which foretold the revolution to come against oppressive taxation and tyrannical rule, is immortalized as “The Boston Tea Party.” Resistance to the British Crown had been mounting since King George imposed the Writs of Assistance, giving British authorities power to arrest and detain colonists for any reason. He also imposed oppressive bills of attainder and authorized troops to “quarter” in the homes of his colonial subjects. Protests intensifed over enactment of heavy taxes, including the 1764 Sugar Act, 1765 Stamp Act and 1767 Townshend Acts. The growing unrest came to bloodshed in March of 1770, when British troops fred on civilians in Boston, killing fve colonists. This event, the “Boston Massacre,” gave rise to the slogan, “No taxation without representation.” But it was the 1773 Tea Act, under which the Crown collected a three-pence tax on each pound of tea imported to the colonies, that instigated many Tea Party protests and seeded the American Revolution. Indeed, as James Madison refected in 1823, “The people of the U.S. owe their Independence and their Liberty, to the wisdom of descrying in the minute tax of 3 pence on tea, the magnitude of the evil comprised in the precedent.” News of the Tea Party protest in Boston galvanized the colonial movement opposing onerous British parliamentary acts that were a violation of the natural, charter and constitutional rights of the British colonists. 2 In response to the rising colonial unrest, the British enacted measures to punish the citizens of Massachusetts and to reverse the trend of resistance to the Crown’s authority. These were labeled “The Intolerable Acts,” the frst of which was the 1774 Boston Port Bill that blockaded the harbor in an effort to starve Bostonians into submission. Among the Patriots who broke the blockade to supply food to the people of Boston was William Prescott, who would later prove himself a heroic military leader at Bunker Hill and Saratoga.

To his fellow Patriots in Boston, Prescott wrote, “We heartily sympathize with you, and are always ready to do all in our power for your support, comfort and relief; knowing that Providence has placed you where you must stand the frst shock. … Our forefathers passed the vast Atlantic, spent their blood and treasure, that they might enjoy their liberties, both civil and religious, and transmit them to their posterity. … Now if we should give them up, can our children rise up and call us blessed?” The Boston blockade was followed by the Massachusetts Government Act, the Administration of Justice Act and the Quartering Act. But far from accomplishing their desired outcome, the Crown’s oppressive countermeasures hardened colonial resistance and led to the convention of the First Continental Congress on September 5th, 1774, in Philadelphia. By March of 1775, civil discontent was at its tipping point, and American Patriots in Massachusetts and other colonies were preparing to cast off their masters. The spirit of the coming Revolution was captured in Patrick Henry’s impassioned “Give me Liberty or give me death” speech. That month, Dr. Joseph Warren delivered a fery oration in Boston, warning of complacency and instilling courage among his fellow Patriots: “The man who meanly will submit to wear a shackle, contemns the noblest gift of heaven, and impiously affronts the God that made him free. … Ease and prosperity (though pleasing for a day) have often sunk a people into effeminacy and sloth. … Our country is in danger, but not to be despaired of. Our enemies are numerous and powerful; but we have many friends, determining to be free, and heaven and earth will aid the resolution. On you depend the fortunes of America. You are to decide the important question, on which rest the happiness and liberty of millions yet unborn. Act worthy of yourselves.” On the eve of April 18th, 1775, General Thomas Gage, royal military governor of Massachusetts, dispatched a force of 700 British Army regulars under Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith with secret orders to arrest Boston Tea Party leader Samuel Adams, Massachusetts Provincial Congress President John Hancock and merchant feet owner Jeremiah Lee. 3 But what directly tied Gage’s orders to the later enumeration of the Second Amendment in our Constitution was the primary mission of his Redcoats: A preemptive raid to confscate arms and ammunition stored by Massachusetts Patriots in the town of Concord.

To his fellow Patriots in Boston, Prescott wrote, “We heartily sympathize with you, and are always ready to do all in our power for your support, comfort and relief; knowing that Providence has placed you where you must stand the frst shock. … Our forefathers passed the vast Atlantic, spent their blood and treasure, that they might enjoy their liberties, both civil and religious, and transmit them to their posterity. … Now if we should give them up, can our children rise up and call us blessed?” The Boston blockade was followed by the Massachusetts Government Act, the Administration of Justice Act and the Quartering Act. But far from accomplishing their desired outcome, the Crown’s oppressive countermeasures hardened colonial resistance and led to the convention of the First Continental Congress on September 5th, 1774, in Philadelphia. By March of 1775, civil discontent was at its tipping point, and American Patriots in Massachusetts and other colonies were preparing to cast off their masters. The spirit of the coming Revolution was captured in Patrick Henry’s impassioned “Give me Liberty or give me death” speech. That month, Dr. Joseph Warren delivered a fery oration in Boston, warning of complacency and instilling courage among his fellow Patriots: “The man who meanly will submit to wear a shackle, contemns the noblest gift of heaven, and impiously affronts the God that made him free. … Ease and prosperity (though pleasing for a day) have often sunk a people into effeminacy and sloth. … Our country is in danger, but not to be despaired of. Our enemies are numerous and powerful; but we have many friends, determining to be free, and heaven and earth will aid the resolution. On you depend the fortunes of America. You are to decide the important question, on which rest the happiness and liberty of millions yet unborn. Act worthy of yourselves.” On the eve of April 18th, 1775, General Thomas Gage, royal military governor of Massachusetts, dispatched a force of 700 British Army regulars under Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith with secret orders to arrest Boston Tea Party leader Samuel Adams, Massachusetts Provincial Congress President John Hancock and merchant feet owner Jeremiah Lee. 3 But what directly tied Gage’s orders to the later enumeration of the Second Amendment in our Constitution was the primary mission of his Redcoats: A preemptive raid to confscate arms and ammunition stored by Massachusetts Patriots in the town of Concord.

The citizen minutemen understood even then that their right to keep and bear arms should not be infringed. Patriot militia and minutemen, under the leadership of the Sons of Liberty, anticipated this raid, and the confrontations between militia and British regulars at Lexington and Concord were the fuse that ignited the American Revolution. Near midnight on April 18th, Paul Revere, who had arranged for advance warning of British movements, departed Charlestown (near Boston) for Lexington and Concord in order to warn John Hancock, Samuel Adams and other Sons of Liberty that the British Army was marching to arrest them and seize their weapons caches. After meeting with Hancock and Adams in Lexington, Revere was captured, but his Patriot ally, Samuel Prescott, continued to Concord and warned militiamen along the way. The Patriots in Lexington and Concord, as with other militia units in New England, were bound by “minit men” oaths to “stand at a minits warning with arms and ammunition.” The oath of the Lexington militia read thus: “We trust in God that, Should the state of our affairs require it, We shall be ready to sacrifce our estates and everything dear in life, Yea, and life itself, in support of the common cause.” In the early dawn of April 19th, their oaths would be tested with blood. Under the command of Captain John Parker, 77 militiamen assembled on the town green at Lexington, where they soon faced Smith’s overwhelming force of British regulars. Parker did not expect shots to be exchanged, but his orders were: “Stand your ground. Don’t fre unless fred upon, but if they mean to have a war, let it begin here.” A few links away from the militia column, British Major John Pitcairn swung his sword and ordered, “Lay down your arms, you damned rebels!” Not willing to sacrifce his small band of Patriots on the green, as Parker later wrote in sworn deposition, “I immediately ordered our Militia to disperse, and not to fre.” But the Patriots did not lay down their arms as ordered, and as Parker noted, “Immediately said Troops made their appearance and rushed furiously, fred upon, and killed eight of our Party without receiving any Provocation therefor from us.” The British continued to Concord, where they divided ranks and searched for armament stores. Later in the day, the second confronta- 4 tion between regulars and militiamen occurred as British light infantry companies faced rapidly growing ranks of militia and minutemen at Concord’s Old North Bridge. From depositions on both sides, the British fred frst, killing two and wounding four. This time, however, the militia commander, Major John Buttrick, yelled the order, “Fire, for God’s sake, fellow soldiers, fre!” And fre they did, commencing with “The Shot Heard Round the World,” as immortalized by poet Ralph Waldo Emerson. With that shot, farmers and laborers, landowners and statesmen alike brought upon themselves the sentence of death for treason. In the ensuing frefght, the British suffered heavy casualties and in discord retreated to Concord village proper for reinforcements, and then back toward Lexington. During that retreat, British regulars took additional casualties, including those suffered in an ambush by the reassembled ranks of John Parker’s militia — “Parker’s Revenge,” as it became known. The English were reinforced with 1,000 troops in Lexington, but the King’s men were no match for the militiamen, who inficted heavy casualties upon the Redcoats along their 20-mile tactical retreat to Boston. “What a glorious morning this is!” declared Samuel Adams to fellow Patriot John Hancock upon hearing those frst shots. Indeed, the frst shots of the eight-year struggle for American independence were in direct response to the government’s attempt to disarm the people.

Thus began the American Revolution — a revolution in support of Liberty not just for the people of Massachusetts but for “all people.” Such rights are not temporal, they are eternal. By the time the Second Continental Congress convened in the Spring of 1775, the young nation was in open war for Liberty and independence, which would not be won until nearly a decade later, at great cost of blood and treasure. In January of 1776, Thomas Paine published his pamphlet Common Sense, which framed the uprising, noting, “The cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind.” Of the justifcation for Revolution, Samuel Adams wrote, “The People alone have an incontestable, unalienable, and indefeasible right to institute government and to reform, alter, or totally change the same when their protection, safety, prosperity, and happiness require it.” On May 15th of 1776, the Continental Congress adopted a resolution calling on states to prepare for rebellion. In its preamble, John Adams advised his countrymen to sever all oaths of allegiance to the Crown.

The Patriot’s Primer on American liberty, 2017

A treatise on the eternal struggle between Liberty and tyranny, and on the primacy of Rule of Law over the rule of men.

Mark Alexander Publisher of The Patriot Post