James Madison’s Council of Revision and Modern Judicial Review

By Rodney Dodsworth – April 15, 2016

While our Constitution famously set up a government of divided powers, the powers within each branch are not absolute. Each is subject to various checks from the others. Congress is responsible for lawmaking, but the president has a qualified veto over congressional bills. It is not absolute, for congress may override on two-thirds majority vote. As a theoretical check on the judiciary, scotus is subject to Article III congressionally determined “exceptions . . . and regulations.”

Scotus has developed a habit of going far beyond its duty to adjudicate between parties and protect the constitutionality of law. Instead, it often vetoes laws based on mere policy disagreements. Viewed another way, scotus regularly exercises an arrogant absolute veto over legislation not granted to any branch of government at all.

If it doesn’t ‘feel right’ to you when scotus substitutes its standards of morality or shoots down a law based on the perceived impropriety of congressional or state statutes, the Framers would agree. At the 1787 Federal Convention, they specifically rejected empowering scotus to veto law based on policy disagreement.

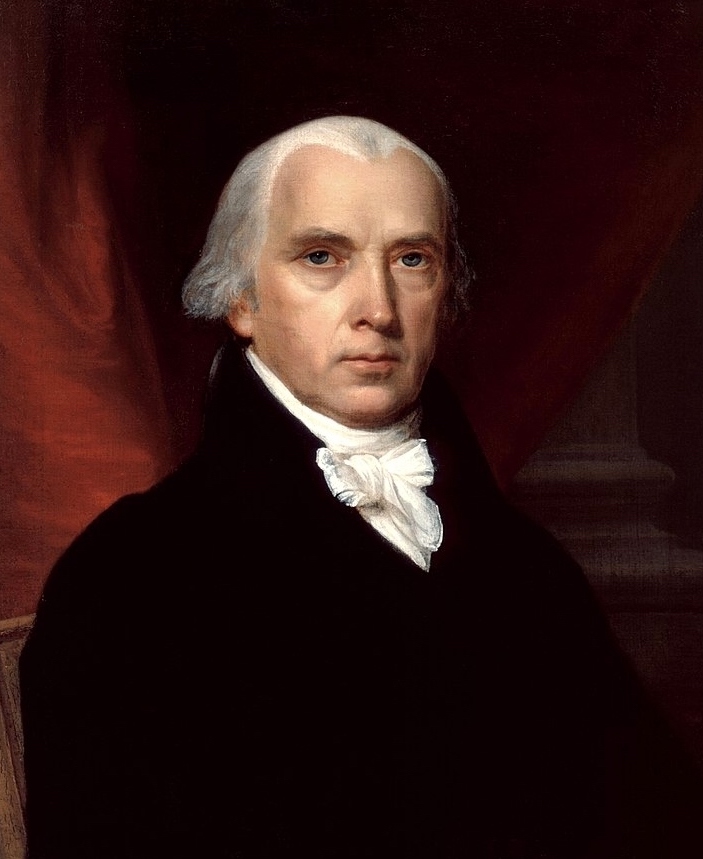

The eighth resolution of James Madison’s Virginia Plan of government proposed a Council of Revision. Comprising the president and a few judges from the supreme court, this body was to examine congressional acts and was empowered to set them aside before they became law.

On June 4th, Elbridge Gerry questioned the propriety of involving judges in “the policy of public measures.” It just wasn’t the business of courts to be involved in judging the wisdom of proposed law. Besides, said Rufus King, “The judges will no doubt stop the operation of such laws as shall appear repugnant to the Constitution.” Looking further into the practical effect of such a council, others agreed that those entrusted with judging the constitutionality of law should not participate in making the law. Debate within the council would surely involve politics and legislative matters far outside the skill set of judges.

The Framers reasoned that unwise laws are not necessarily unconstitutional and to the extent the judiciary is involved in lawmaking, their prestige in adjudicating the law is diminished. Let the congress and president exercise political judgment and reserve judicial review to scotus subsequent to operation of the law. The combined executive/judicial veto of Resolution Eight was refined into the qualified executive veto we know today.

To deal with the unconstitutional, de facto absolute judicial veto, one of Mark Levin’s proposed liberty amendments might provide relief. An Amendment to Establish Term Limits for Supreme Court Justices and Super-Majority Legislative Override would work to minimize judicial overreach.

First, by limiting the term of scotus judges to twelve years, his amendment would reduce the impact of the typical judge’s leftward drift in office. Second, by a three-fifths vote of the state legislatures the states may override any scotus majority opinion.

Term limits for justices would bring the typical judge down from Olympus and into the earthly world before he could go senile or full loony-tune Leftist. Knowing that a power higher than themselves will immediately look over their shoulders and judge the judges, the rampant and unhinged social justice warrior temperament of scotus will be subdued.

Members of congress are so loathe to risk reelection, there is zero chance such an amendment could ever emerge from that once august body. These and other corrections to our governing system can only emerge from the sovereign people via their states.

We are the many; our oppressors are the few. Be proactive. Be a Re-Founder.