[Editor: this Feature is a collection of brief essays on the Electoral College myths by Tara Ross that have previously appeared individually in Hunt For Liberty]

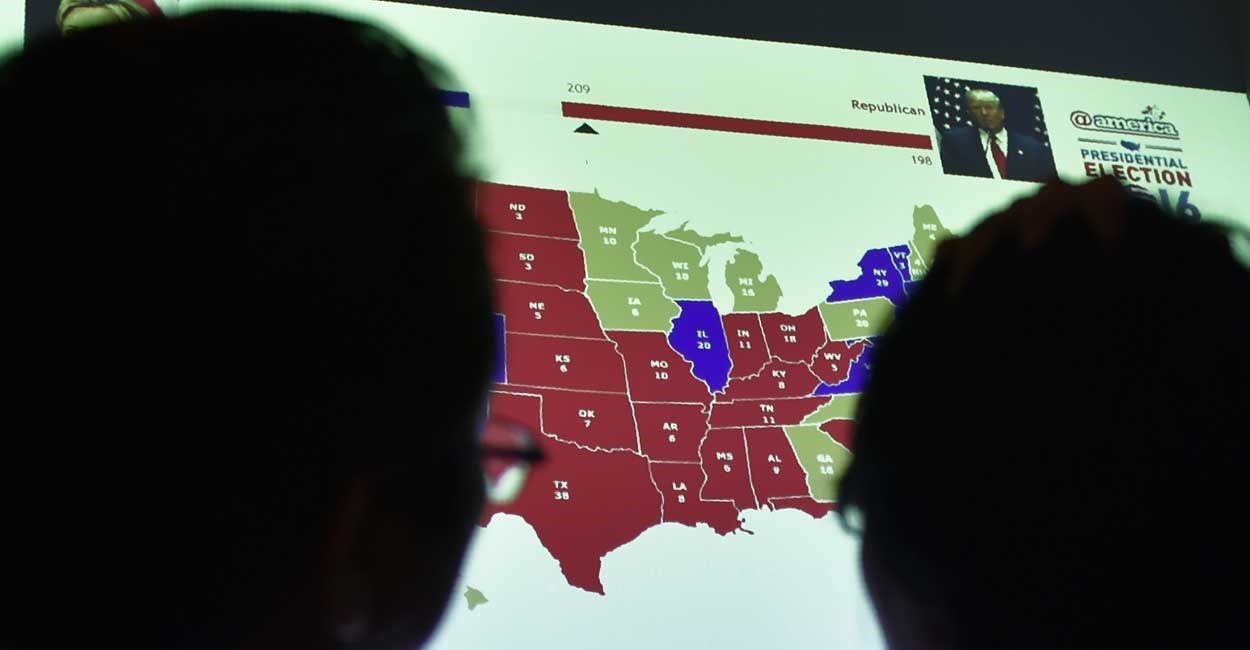

Electoral College Myth #1: Only swing states matter. Other states are ignored.

Myth: Most states are ignored by presidential campaigns because of the Electoral College. Only swing states matter. A direct election system would fix this.

Fact: There are two reasons why this perception is incorrect.

First, an honest assessment of American history shows that no state is permanently “safe” or “swing.” The identity of these states changes all the time. In recent years, we’ve heard a fair amount of commentary about “new” swing states such as Virginia or North Carolina. We even hear talk this year that Utah is competitive, with third party candidates Evan McMullin and Gary Johnson showing surprising strength.

Remember that Texas used to vote Democratic. California used to vote Republican. George W. Bush won his victory in 2000 with the help of one state that was supposed to be a safe blue state: West Virginia. A whole slew of southern states voted for Bill Clinton, but they never voted for Barack Obama. In other words, even if “only swing states matter,” these states are constantly changing.

Second, presidential elections are not only about the TV commercials and campaign visits in the final weeks and months leading into Election Day. Presidential elections are as much about the four years of governance before the election as they are about the final commercials. How did California voters react when President Barack Obama decided not to allow construction of the Keystone Pipeline? How did Texas voters react when President George W. Bush issued his executive order prohibiting the use of federal funds for certain types of embryonic stem cell research? How many voters will not vote for Hillary Clinton under any circumstance because of Benghazi? How many voters are bound and determined to vote Democrat because they want to protect Obamacare? Such decisions and their ramifications are part of governing, but they are also at least a part of “campaigning.” They do as much as a TV commercial (if not more) to influence voting decisions—as candidates and incumbents certainly know.

In short, “safe” states are not being ignored. They have simply already made up their minds based upon the years of decisions that preceded the election. When a state ceases to be satisfied, it quickly lets its political party—and the world!—know. Such states either become safe for the opposite political party (as West Virginia did following the election of 2000) or they become a new swing state (as Virginia recently has).

At the end of the day, political parties and presidential candidates can’t ever ignore any state unless they want to risk losing that state’s electoral votes.

Please don’t miss my new kids’ illustrated book about the Electoral College!

Signed copies available at the bottom of THIS PAGE.

If you have Amazon Prime, shipping will be much cheaper with (unsigned) copies HERE.

This entry was posted in Electoral College resources. Bookmark the permalink.

***

Electoral College Myth #2: The Founders did not trust the people

by Tara Ross September 6, 2016

Myth: The Founders created the Electoral College because they did not trust the people to govern themselves.

Fact: The Founders knew that the voice of the people must be reflected in any government if it is to be legitimate. At the Constitutional Convention, George Mason, delegate from Virginia, expressed this sentiment when he declared that “the genius of the people must be consulted.”

Remember, the Founders had just fought a Revolution because the colonies had no representation in the British Parliament! They’d laid their lives on the line for this principle of democracy. They were not likely to give up on it so soon.

On the other hand, the delegates to the convention knew their history, and they knew that pure democracies can be dangerous. After all, in a pure democracy, 51 percent of the people rule the other 49 percent. All the time. Without question. The Founders knew that, as a matter of history, these types of pure democracies implode. Why? In the heat of the moment, even bare or emotional majorities can impose their will upon the rest of the people. Moreover, they also knew that, even if the American colonies had been given representation in the British Parliament, Americans would have been outvoted time and again by the majority of citizens at home in England.

In short, political minorities must be protected from tyrannical and unreasonable majorities if a country is to survive. James Madison, delegate from Virginia, put it this way:

[In a pure democracy], [a] common passion or interest will, in almost every case, be felt by a majority of the whole; a communication and concert results from the form of government itself; and there is nothing to check the inducements to sacrifice the weaker party or an obnoxious individual. Hence it is that such democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths.

The Founders wanted to create a self-governing society, but they also wanted to protect political minorities from the dangerous dynamics described by Madison. They solved their problem by drafting a Constitution that would incorporate the best elements of democracy (self-governance), republicanism (deliberation and compromise), and federalism (states are able to act on their own behalves).

America is self-governing, but our Constitution also provides political minorities with tools that protect them from the tyranny of the majority: For instance, we have a presidential veto. We have supermajority requirements to amend the Constitution. We have a Senate (one state, one vote representation), as opposed to the House (one person, one vote representation). The Electoral College is simply another of these protective devices.

The delegates to the Convention felt that they had created a presidential election system that would allow the majority to rule, even as it protected political minorities from tyrannical rule. It is for this reason that Madison declared, “He [the President] is now to be elected by the people.” Another delegate, Alexander Hamilton, agreed that the new election system would allow the “sense of the people” to “operate in the choice of the [President].”

“The Founders did not trust the People” makes a snazzy sound bite. But the history of the Constitution and its Electoral College shows a much more nuanced picture.

Please don’t miss my new kids’ illustrated book about the Electoral College!

Signed copies available at the bottom of THIS PAGE.

If you have Amazon Prime, shipping will be much cheaper with (unsigned) copies HERE.

This entry was posted in Electoral College resources. Bookmark the permalink.

***

Electoral College Myth #3: The Electoral College is undemocratic

by Tara Ross September 13, 2016

Myth: The person who wins the national popular vote should win the White House. The Electoral College does not guarantee such results and is thus undemocratic.

Fact: The question is not “democracy” v. “no democracy.” The question is “democracy with federalism” (the Electoral College) v. “democracy without federalism” (a direct popular vote).

What is federalism? Federalism is a reference to the fact that power in this country is divided between a single, national government and the state governments. The Constitution gives our national government in D.C. power in certain areas. All other power is left to the states or to the people themselves. In the context of presidential elections, the states are the driving factor behind the selection of electors and the Electoral College vote. We don’t hold one single, national election for President. As the system operates today, we hold many separate elections, one in each state.

Think about it. Are we really kicking democracy entirely out of the process? In this country, Americans participate in 51 purely democratic elections each and every presidential election year—one in each state and one in D.C. This first phase of the election is what you think of as “Election Day.” These purely democratic, state-level elections determine which individuals (electors) will represent their states in a second phase of the election. Part Two of the election occurs in December—with much less media fanfare!—and is a federalist election among the states. There are 538 electors who participate in this election. A majority of them (270) can elect a President.

America’s unique blend of democracy and federalism has served the country well because it encourages presidential candidates to create national coalitions. A candidate must do more than simply rack up a majority of voters in one region or among the voters of one special interest group. He must appeal to a variety of Americans before he can win 270 states’ electoral votes. A direct popular election would not create the same set of incentives. Instead, the candidate who obtains the most individual votes—even if they are obtained exclusively in one region or in a handful of urban areas—would be able to win the presidency.

This year’s election has been a bit problematic, at least in part, because our political primaries veer from the healthy incentives that I’ve just described. Whereas the Electoral College encourages coalition-building, the primaries encouraged divisiveness. And while the Electoral College requires candidates to win the support of a majority of states’ electors, the primaries did not require a majority of anything. Instead, bare pluralities were sufficient for victory.

Is it any wonder that we’ve been less and less satisfied with the results of our political primaries as they become more purely democratic over time? Is it any wonder that both Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton are having trouble building coalitions now?

America is a large and diverse country, composed of both large and small states. It deserves a unique election process, ensuring that all voices are heard in the election of its President. The Electoral College, with its combination of democracy and federalism, has served the country well in this regard for more than 200 years. Perhaps the political parties could learn a thing or two when they consider how to change their political nomination processes in 2020.

Please don’t miss my new kids’ illustrated book about the Electoral College!

Signed copies available at the bottom of THIS PAGE.

If you have Amazon Prime, shipping will be much cheaper with (unsigned) copies HERE.

This entry was posted in Electoral College resources. Bookmark the permalink.

***

Electoral College Myth #4: Votes cast for a 3rd-party candidate are wasted

by Tara Ross September 20, 2016

Myth: We are stuck with the two major party choices. A vote for a third-party candidate is wasted.

Fact: The Electoral College strikes a better balance than that.

Yes, the Electoral College reinforces the two-party system, which is an overall good thing. We really don’t want to devolve into a multi-party, fractured state of affairs like you sometimes see in Europe….or like we saw in this year’s Republican primaries?! :/ As the Electoral College reinforces the two-party system, it also encourages Americans to work together and to unify. It encourages us to focus on our similarities, not our differences. It makes it hard for extremist 3rd-party candidates (e.g., George Wallace) to gain traction. All good stuff.

On the other hand, the Electoral College does allow large, reasonable third parties to influence the process. Major parties do implode and can be replaced when they become too unhealthy. Consider that Abraham Lincoln was elected as the Whig Party was dying and the Republican Party was just getting started. His win as the nominee of a relatively new party was pretty unusual, of course. Typically, third parties don’t win, but they can influence the process in other ways. Consider the election of 1992: Ross Perot ran a large, healthy, third-party campaign that year. His Reform Party ticket didn’t win even a single electoral vote, but it did capture the attention of both of the major parties. In the years that followed, both Democrats and Republicans worked to address the financial concerns of Perot voters. His campaign achieved something, even if that something wasn’t the White House.

A somewhat similar dynamic existed in 1912, when the Republican vote was split between incumbent President William Howard Taft and former President Teddy Roosevelt. In a weird twist, the incumbent President’s campaign was effectively the third-party ticket that year. In the end, Taft earned only 8 electoral votes, compared to Roosevelt’s 88. Democrat Woodrow Wilson won in a landslide with 435 electoral votes. Nevertheless, Taft’s supporters felt that they’d achieved their goal: to preserve a constitutionalist arm of the Republican Party. To be fair, Roosevelt supporters were more focused on the flip side of this same coin: They felt that Taft’s supporters had handed the election to Wilson.

This year is an interesting year, to say the least. What does a third-party vote look like this year? Is it like 1912 & 1992 . . . or could it possibly be more like 1860?

If we look to historical precedent, the answer is pretty simple: It’s extremely unlikely that a third-party candidate could win. The most likely scenario is that we end up with either President Clinton or Trump. But here’s the counterargument to that prediction: Polls show that the single biggest coalition in this country is the coalition of people who don’t want Clinton OR Trump. If that coalition ever got a face, then who knows what might happen? After all, the Electoral College rewards coalition-building.

Going back to the original question: Does the Electoral College rob voters of choices? No, it does not. But it does make the decision to vote third-party a more difficult one: When are things so bad that you will deviate from one of the two major parties? Do you think that enough people agree with you? Will your third-party vote have the effect that you want it to have? Are you willing to cast that ballot only if you are guaranteed an 1860-like outcome? Or are you satisfied with a 1912 or 1992-like statement?

In short, with the Electoral College in place, a third-party vote is best cast thoughtfully, not emotionally. But voters are not “stuck” with only two choices unless they believe they are.

Please don’t miss my new kids’ illustrated book about the Electoral College!

Signed copies available at the bottom of THIS PAGE.

If you have Amazon Prime, shipping will be much cheaper with (unsigned) copies HERE.

This entry was posted in Electoral College resources. Bookmark the permalink.

***

Electoral College Myth #5: Eliminating the Electoral College will make it harder to steal elections

by Tara Ross September 27, 2016

Myth: In 2000, a few hundred stolen votes in Florida could have changed the outcome of the presidential election. Such examples show that elections are too easy to steal with the Electoral College in place. Eliminating the system will make it harder to steal elections.

Fact: To the contrary, elections will become easier to steal if the Electoral College is eliminated.

In order to steal an election today, you need a few things going your way: First, at the national level, the election needs to be close enough so that only one or two altered state outcomes will change the final results. Second, at the state level, the margins in these contested states must also be very close. As a matter of history, such elections are fairly rare. The election of 2000 was one such election: Florida was a close race that could have changed the outcome. The election of 1960 was another: Texas and Illinois had narrow margins and could have flipped the election to Nixon. Most elections are won by wider margins.

Assuming the election is this close, however, you must meet one final criterion: You must predict, in advance, the identity of the state(s) in which stolen votes will influence the final results. This is hard to do. In 2000, no one knew in advance that a few hundred stolen votes in Florida could change the election outcome. In fact, if the media had not called the state for Gore too early—before polls closed in the Republican-leaning panhandle—such a narrowly decided result might never have come about. However, imagine that you can make such a prediction. If you can do it, then probably many people from both parties have made the same prediction. Think Ohio in 2004: Many people were worried that the state’s results would determine the identity of the President. As a result, poll watchers and lawyers from all over the country descended upon the state. It was probably not impossible to steal votes in Ohio that year (because it is never impossible), but it was as difficult as possible.

Now consider a world without the Electoral College. Suddenly, the situation is reversed. Any vote stolen in any part of the country can change the outcome of an election. Even votes that are easy to steal suddenly become critical to the national outcome. Imagine how easy it must be to steal votes in the bluest of California or reddest of Texas precincts. These easily stolen votes are now able to change the national outcome. There is no need to predict which swing state could change the outcome of the election. Any vote stolen in any part of the country—no matter how easy it was to steal—makes a difference. This is a dangerous situation and the opposite of what we have now.

An interesting dynamic in our current system is that it is usually easy to steal votes where it does not matter to the national outcome (e.g., safe states dominated by one political party) and hard to steal votes where it might matter (e.g., swing states, which are usually well-watched with poll watchers, etc.).

It is probably naïve to believe that fraud can ever be completely eliminated (although that would certainly be nice). But the Electoral College at least makes it as difficult as possible.

Please don’t miss my new kids’ illustrated book about the Electoral College!

Signed copies available at the bottom of THIS PAGE.

If you have Amazon Prime, shipping will be much cheaper with (unsigned) copies HERE.

This entry was posted in Electoral College resources. Bookmark the permalink.

***

Electoral College Myth #6: Eliminating the Electoral College would make every vote equal

Myth: A national direct election system would be better than the Electoral College. It would force presidential candidates to run truly national campaigns because votes in every corner of the country would have the same weight. Every voter will matter only if every vote is equal.

Fact: The real question is not whether voters are or are not equal with each other. Every voter in this nation is equal with every other voter in his same election pool. The question is whether the relevant election pool should be one national election pool or 51 state (plus D.C.) election pools. Second, it’s important to remember that there is an important difference between giving votes the same legal weight and making voters equal in practice.

Perhaps it helps to remember how our system operates today. Americans don’t hold one single, national election for President. Instead, we have an election that operates in two phases. In the first phase of the election, Americans participate in 51 completely separate elections—one in each state and one in D.C. The purpose of these purely democratic, state-level elections is to determine which individuals (electors) will represent your state in a second phase of the election. In these state-level elections, your vote carries the exact same weight as every other voter in your election pool! In other words, every vote cast in Kentucky has the same legal weight. Likewise, every voter in Florida is equal with every other voter in Florida.

The second phase of the election occurs in December. This latter election is an election among the states’ 538 electors, which were elected on Election Day. A majority of them (270) can elect a President.

Electoral College opponents correctly note that eliminating the Electoral College would change our two-phase process into a single, national election. Thus, instead of votes that have the same legal weight at the state level, we’d have votes that have the same legal weight at the national level. But there is an important difference between making voters legally equal and making them equal in practice. If we conduct one single national election, we will have the former, but not the latter. If we keep our current system, we ultimately do better with both.

Presidential candidates have limited time and resources; they must strategize and prioritize. They won’t run out to a remote city like Worland, Wyoming, simply because the 4,000 potential votes there have the same legal weight as 4,000 votes cast anywhere else in the country. As a strategic matter, candidates are immensely more productive if they head to a large urban area to get those 4,000 votes. It’s simple math. In a big city like Los Angeles, they will obtain not only 4,000 votes but probably millions more. In a world without the Electoral College, rural areas and small states will never again matter in the presidential election. It won’t matter that their votes have the same legal weight as voters in big cities. Practically speaking, candidates have little incentive to care how they vote.

The Electoral College, by contrast, forces presidential candidates to broaden their appeal as much as possible. If a candidate has already won California, then the 4,000 extra votes in Wyoming or another small state really might be what he needs. He doesn’t need any more votes in L.A. His campaign strategy must take into account the fact that his support must cross state and regional boundaries if he is to win a majority of states’ electoral votes.

Electoral College opponents sound irrefutable when they argue that the Electoral College should be eliminated because “every vote should be equal.” They forget—or choose to ignore—that the Founders incorporated state action into our presidential election system for very important reasons. And it turns out that giving votes equal legal weight within state boundaries (instead of national boundaries) ensures that voters are not only legally equal, but also much more equal as a pragmatic matter.

Please don’t miss my new kids’ illustrated book about the Electoral College!

Signed copies available at the bottom of THIS PAGE.

If you have Amazon Prime, shipping will be much cheaper with (unsigned) copies HERE.

This entry was posted in Electoral College resources. Bookmark the permalink.

***

Electoral College Myth #7: The System Disenfranchises Voters Who Live in “Safe” States

Myth: Most voters don’t count in presidential elections. The winner-take-all allocation of electoral votes in the states ensures that some voters are disenfranchised, left on the sidelines to watch, as voters in swing states determine the outcome of the election. Why bother to cast a Democratic vote in Texas or a Republican one in California? These are wasted votes.

Fact: To “disenfranchise” is to take away a person’s right to vote. No one in this country is losing his right to cast a ballot. This is a strong (and baseless) allegation that reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of our Electoral College system works today.

America’s presidential election process occurs in two phases: The first phase is a series of state-level elections that occurs on Election Day. We conduct 51 of these elections: one in each state and one in the District of Columbia. The purpose of these 51 elections is to determine who will represent each state in the second phase of the election: an election among the states. This second phase of the election occurs in December and will be a mere blip on the media’s radar.

Each of the 51 elections conducted on Election Day is a purely democratic election; every voter in every state retains his right to cast a ballot. Of course, as in any other election, there will be winners and there will be losers. The losers are not disenfranchised. They simply cast a ballot on the losing side of an election.

Let’s say it another way: If you are a Republican casting your ballot in California, you will probably be on the losing side of the state-level election in California. More than likely, Hillary Clinton will carry California and obtain its 55 electoral votes. However, California Republicans are most emphatically not being disenfranchised. They are simply losing the election, just as they lost the last gubernatorial election. Their problem is not with the Electoral College. Their problem is a general one about how the Republican Party’s message is being received around California.

By the way, this can change. As recently as 1988, California was voting safely RED, not BLUE. And this year’s election is already disrupting many long-held assumptions about how states will vote.

Finally, remember that the winner-take-all system is not mandated by the Constitution. If a state wants to change to a different system of electoral allocation, it is welcome to do so. In fact, Maine and Nebraska have already made such a change. Their votes are allocated based upon congressional district.

To be fair, it should be noted that the state legislature does retain the right to select the electors on its own, without reference to a popular vote. Historically, this has only occurred in special circumstances. For instance, the Colorado legislature directly selected electors in 1876, shortly after it became a state. It had just held elections for its statewide offices in August, and it did not want to go to the expense of another election so soon. Similarly, in 2000, the Florida state legislature was prepared to appoint electors directly if disputes over its state’s ballots could not be resolved.

As a general matter, however, those few instances have been the exception, not the rule. Allegations that voters are being “disenfranchised” by the Electoral College are mere melodrama. America conducts 51 purely democratic elections each and every presidential election year; every voter in these elections retains his right to participate fully. What Electoral College opponents really mean by their claims of “disenfranchisement” and “waste” is that they feel emotionally better about one national, democratic election than 51 state-level, democratic elections.

For a discussion of the reasons that our Founders combined state action with democracy, please see my post on the subject, here.

Please don’t miss my new kids’ illustrated book about the Electoral College!

Signed copies available at the bottom of THIS PAGE.

If you have Amazon Prime, shipping will be much cheaper with (unsigned) copies HERE.

This entry was posted in Electoral College resources. Bookmark the permalink.

***

Electoral College Myth #8: Candidates who lose the popular vote shouldn’t win the White House. The system is rigged!

Myth: If a candidate wins the popular vote, but loses the electoral vote, that is inherently unfair. The system is rigged! The winner of the national popular vote should be President.

Fact: In any game, rules are established for a certain purpose. I’ve noted before that America’s traditional pastime, baseball, is relevant in this regard. Any baseball fan knows that teams do not get to the World Series by scoring the most runs throughout the course of the season. Instead, teams earn their spot in the playoffs by winning the most games in their league. Naturally, rules could be established that would allow the two teams that score the most runs to play in the World Series, but such rules would not accomplish the stated objective of a championship game: Allowing the two best overall teams to face off at the end of the year.

A revised set of rules might allow a team, for instance, to earn a spot in the World Series by having one great month and several poor months. Or perhaps a team that is great at taking advantage of weak opponents (but rather poor at facing off against good opponents) would win a berth in the World Series. Excellent performances throughout the baseball season would not be required to earn the championship. Occasional, stellar performances could be sufficient.

The rules for the presidential election contest are established with a similar purpose. They seek to identify the best national candidate, overall. The system leans in favor of candidates whose strengths play out evenly, rather than those who perform brilliantly in one part of the country but terribly in other regions.

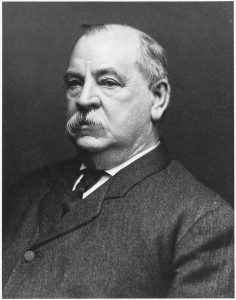

A historical example demonstrates how well this process tends to work.

In 1888, Democrat Grover Cleveland was running against Republican Benjamin Harrison. At the time, several events had led to a perception that Cleveland, then the incumbent President, was a candidate who cared only about the South and southern issues. Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, Cleveland won huge landslides in six southern states on Election Day. He won 72.2 percent of the votes cast there! By contrast, Harrison had run a campaign that was not so focused on a single region and its concerns. He didn’t have such large margins of victory in any part of the country, but he did have a more diverse coalition and he’d won states across various regions.

In the end, Cleveland won the popular vote with 5.5 million votes compared to Harrison’s 5.4 million; however, he lost the Electoral College vote, 233-168. The popular vote loser, Harrison, was elected President.

This was a good outcome! If Cleveland had won the presidency this year, then he would have done so based on the votes of only six states. Should six southern states be able to trump the rest of the country and put its own candidate in office? The Electoral College did its job that year: It gave the presidency to the candidate who had built the best coalition, composed of the greatest variety of voters.

Cleveland himself seems to have learned this lesson. Four years later, he ran a campaign with more broad-based appeal, and he was elected President in 1892.

Please don’t miss my new kids’ illustrated book about the Electoral College!

TaraRoss.com