Federal Debt is a Threat We Must Address

By Robert Charles – August 2020

The United States confronts security threats of varying kinds—foreign and domestic, visible and invisible, immediate and creeping. Arguably, the most significant domestic, invisible, creeping threat is runaway debt. It can be addressed, and it must. For that, we need leaders to lead.

Thomas Jefferson, our third president, wrote, “I place economy among the first and most important of virtues, and public debt as the greatest of dangers to be feared.” Accordingly, he didn’t ignore the threat of debt, even in his time.

When Jefferson assumed office in 1801, our national debt—resulting from the Revolutionary War and young Navy—stood at $83,038,050. When Jefferson left in 1809, having spurred the economy, dispatched Barbary Pirates, financed Lewis and Clark, and doubled America with the Louisiana Purchase, he had cut our debt to $57,023,192, or by 32%.

In short, while wars, recessions, depressions, and the modern contrivance of mass entitlement programs (after 1965) have continuously raised America’s debt, out Founders were intensely focused on not overspending.

Why? The answer is simple. Those who founded the country were concerned that runaway national debt would drain revenue from future generations (in higher taxes) to pay for the living.

Focused on concepts like equal protection and due process, seeking to assure a sustainable republic, and aware that intergenerational debt disincentivizes repayment, they thought overspending, a passing debt from generation to generation, was more than unfair—it was immoral.

John Adams, our second president, noted, “There are two ways to enslave a nation: one is by the sword, and the other by debt.” Even Alexander Hamilton, who proposed the national bank , said, “Allow a government to decline paying its debts, and you overthrow all public morality; you unhinge all the principles that preserve the limits of free constitutions.” You hobble the future.

Our Founders would be speechless to see our national debt above $26,000,000,000,000 dollars—that is, 26 trillion dollars. Just see the US debt clock at usdebtclock.org.

So, how did we get here? What does it mean for America’s future? How do we escape this debt trap? The bad news is decades of federal indifference, irresponsible leadership, and vote-buying created this mess. The good news is there are ways out. Time to face our moral obligations.

The “how we got here” part is no mystery. For almost two centuries, the federal debt grew slowly, chiefly by wars—especially the Civil War—and slow repayment. Politicians have always found raising taxes harder than assuming more debt.

During the first half of the 20th century, federal reluctance to assume debt—coupled with World Wars I and II and the Depression—bumped unpaid federal obligations from $3 billion in 1915 to nearly $253 billion by 1949.

Two periods of outright irresponsibility then marred the next 70 years. One was President Lyndon Johnson’s creation of the entitlement state in the 1960s. His vision, articulated as “The Great Society,” was one that banished poverty by imposing dependence and concentrating power. Unfortunately, he got the last two but not the first.

Johnson, by his own admission, envisioned a lock on future elections by assuring people would be dependent on a party willing to pay them to, in effect, pay them. That is, he understood the flip side of the Founders’ warnings about federal debt: political gain from distributing benefits.

Benjamin Franklin noted, “When the people find that they can vote themselves money, that will herald the end of the republic.” As Alexander Tyler observed, democracy “can only exist until the voters discover that they can vote themselves largesse from the public treasury” and “from that moment on, the majority always votes for the candidates promising the most benefits […].”

Starting in the 1960s, entitlements—or non-discretionary spending—took off. Presidents of both parties, as Benjamin Franklin predicted, found turning off the tap harder than turning it on. Reigning in the rip of promised federal money, even as federal debt rose, proved hard.

Federal debt rose from $311 billion in 1964 to nearly a trillion when Ronald Reagan took office in 1981 and to $2.6 trillion when he left office, having cut taxes and ended the Soviet Union—only to begin a run-up to $6 trillion in 2001, when George W. Bush took office.

Quantifying the Federal Debt

The US Treasury’s official figure for the debt of the federal government on June 18, 2020 was $26.2 trillion—or more precisely–$26,233,671,903,404. This amounts to:

- $79, 562 for every person living in the US.

- $204,028 for every household in the US

- 8% of annual US economic output

- 2 times annual federal revenues.

- 61% more than the combined consumer debt of every household in the US.

Source: JustFact.com

The second Bush—who expanded entitlements, managed 9/11, and initiated wars in Afghanistan and Iraq—drove debt to $10 trillion. His successor, Barack Obama, then allowed federal debt to double in eight years, hitting $19.5 trillion by the time Donald Trump was inaugurated.

The past three years have been marked by struggle—unprecedented economic growth paired with inescapable federal debt. Aiming to replay Reagan’s economic renaissance—which followed a 23% tax cut in 1981—President Trump secured the largest tax cut in decades.

He cut corporate taxes from 35% to 20%, doubled the standard deduction, and repealed the Obamacare tax, remaking our federal tax code and rolling back regulations. From a growth perspective, it worked. Every major sector and demographic grew, setting records and boosting federal tax revenues. Pushing trade fairness, especially with China, grew other revenue.

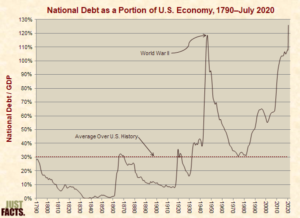

National Debt as a Portion of US Economy, 1790-2020

On May 22, 2020, the national debt reached 118.5% of the nation’s annual economic output, breaking a record set in 1946 for the highest debt in 230+ year history of the United States. The previous record of 118.4% stemmed from World War II, the deadliest and most widespread conflict in world history. By the end of May 2020, the debt had risen to 119.5% of GDP, or four times its average over the nation’s history:

Then, the Chinese-origin COVID-19 virus hit us broadside, followed by national unrest, which slowed America’s economic reopening, reduced consumer confidence, left billions in business damage, and triggered the spread of a second viral wave. All this was unplanned.

Interestingly, federal debt only edged up $2.5 trillion in Trump’s first three years, despite increased defense spending. The economy’s capacity to pay off debt rose. A booming, non-inflationary economy held interest rates on federal debt low. All that was good.

Unfortunately, COVID-19’s economic lockdown was a goose strike on takeoff, effectively requiring emergency action. To the president’s credit, he and the Federal reserve moved fast to restart the economy, but the costs—again—have registered in debt.

The double whammy of the virus and the unrest triggered a need for federal stimulus to save businesses unable to recover on their own. The first law was $8.3 billion, the second $192 billion, the third $1.8 billion. There measures aimed to save consumers, businesses, and the economy.

Today, we are facing federal debt of more than $26 trillion as indicated above. The impact is manifold. The more debt we carry, the less liquidity exists for private investment (which gets crowded out), the less room there is for non-discretionary spending (e.g., for defense, intelligence, cyber, border, and security), the more we waste on interest (projected at $6 trillion over ten years), the more tenuous Social Security and Medicare are, and the less flexibility we have for future crises.

Since there is no such thing as a free lunch, the biggest single impact is a moral failure. We are enslaving, to use John Adam’s term, those who will come after us—our children, their children, and those who must pay this debt down. In effect, we have spent what they will earn. We have lived on their nickel and cursed them with our irresponsibility.

Is it all dark? What can be done? No, it is not all dark. In truth, five means exist for extracting ourselves from this enormous debt, which in 2021 will produce a 136% debt-to-GDP ratio. Four of these ways are good, and one is not.

“As a very important source of strength and security, cherish public credit. One method of preserving it is to use it as a sparingly as possible, avoiding occasions of expense by cultivating peace, but remembering also that timely disbursements to prepare for danger frequently prevent much greater disbursements to repel it, avoiding likewise the accumulation of debt, not only by shunning occasions of expense, but by vigorous exertion in time of peace to discharge the debts which unavoidable wars may have occasioned, not ungenerously throwing upon posterity the burden which we ourselves ought to bear.”

George Washington, Farewell Address, 1796

Regarding the first of the positive means, we can restart our economy and restore jobs and confidence to the level Trump achieved in early 2020, allowing debt repayment with elevated growth and higher tax revenues. That is the magic—proven by both Reagan and Trump—of supply-side economics.

Second, we can elect officials who are fiscally responsible, not socialist spendthrifts and liberty killers but those who prioritize cutting waste, fraud, abuse, and self-perpetuating federal programs, even as they restructure entitlements to reflect need, phase-in periods, reliance on private-sector options, and grandfather clauses.

Third, changes in the tax code can trigger greater savings, even as a restored high-growth economy adds revenue through increased consumption.

Fourth, leveling the international playing field, reducing unfair trade practices, holding unfair actors like China accountable, rewarding domestic efficiency, and leveraging tariffs can produce long-term savings.

Finally, since the truth cannot be hidden and our Founders were right to fear debt and the despotism of unaccountable leaders, unchecked debt does produce a fifth way out. That is rampant inflation, which reduces the dollar’s value, defaulting to foreign holders and Americans who paid into Social Security and rightly expect medical care in older age. That is the route out we do not want.

In short, America was founded on liberty, limited government, and responsible leaders who were resolved to not get us into deep debt. Now that we are here, we must ensure that the next generation of leaders knows that getting out of debt matters.

This November will present stark choices—socialist-leaning options, content with irresponsible overspending, dependence, suppressing liberty, and centralizing government—and those who oppose that view. If we are to get back on track, George Washington’s words should ring in our ears: “As a very important source of strength and security, cherish public credit […]” rather than “ungenerously throwing upon posterity the burden which we ourselves ought to bear.” In short, we need leaders who will lead by prioritizing security, accountability, and lower federal debt.

[Editor: other solutions not considered here might be an Article V state amending convention to discuss the application of the Swiss Debt Brake, or setting limits on taxing and spending, or a balanced budget, in the Constitution]